Begin as you mean to go on.

Stagger toward consciousness under the insistent paws of the older cats, wondering where breakfast is. Sit up, fish last night’s sweater from the floor, slip into it. Quietly to the bathroom to void the bladder and wonder, vaguely, if the toilet’s recently sluggish drain is merely due to an uptick in toilet paper usage, that might be remedied by a faintly stern lecture at some point, or something deeper, older, more severe, that will at some point require professional help. Into the kitchen, followed by the aforementioned cats, but quietly, quietly; it may be an hour later than usual, but it’s still some hours before everyone else. Switch on the kettle, crack open a can, a spoonful each in the bowls of the older cats. Grind the coffee. Rinse out the French press. As the water works its way to a boil, stick a head in the daughter’s room to check on the kitten, who’s sat, alert but sleepy, on her sleeping shoulder. Tip out the ground coffee. Stir in the water just off its boil. Mix up the poolish for the pompe a l’huile, and notice for the first time that the recipe just says “salt,” and not how much. Figure it’s a teaspoon, given everything else, but that’s for later, after the poolish has had time to ferment. Plunge the coffee, pour it into the thermos, pour out a cup. Sit down. Light the candle. Draw the card. Fire up the keyboard and turn to the first draft of the first scene of the thirty-fifth novelette. Figure maybe it’s time to commit to the occasional use of a question mark as an aterminal mark of punctuation, indicating a rising tone in the middle of a sentence, but not the end of it—but only in dialogue, and only when separated from the rest of its statement by some sort of dialogue tag? he said, uncertainly, but sure, okay, let’s do it. And what about whether or not he straight-up asks her where she’s going: say that out loud? Let it be inferred? Decide. Decide. There’s three more scenes to edit today to hit the pace we’d like. Let’s go.

20/20 hindsight.

What did I do this year, the year we decided to do the same thing we do every year, which is to bring blogging back. —Besides get translated and publish a book and begin the process of de-Amazonification and put out a ’zine and write another novelette, none of which is blogging, per se. Let’s see: I rather like this one, which only looked like it was sort of mostly about Watchmen, and this one, which is really mostly David Graeber, only then he had to go and die. This one, about book design and Entzauberung, is the sort of post I’d like to think I miss most about blogging; this one, about comics and formalism and serials, I’d like to think could’ve been, if maybe I’d worked it over one more time; this is the sort of genial shit-talking I always think these days I never have the time for anymore, even though they don’t take long at all; and this is the sort of thing commonplace books were intended for, I’d like to think. And I’m most awfully fond of this one (another entry in the Great Work) and most especially this one (yes), if not so much the third in the sequence, which wasn’t ever really supposed to be a sequence, but I’m sure you’re noticing all of these are from, like, the very beginning of the year? Before the Occupation of Portland by the zelyonye chelovechki, before the election and its ghastly aftermath sped up the grindingly long-term fascist coup enough for everybody else to see it, before the pandemic really settled in and took hold, and the bleakly short-sighted stupidity, and, well, I mean, 2020, y’know? I mean, it’s not like I gave it up entirely, I was still posting stuff I’d include in a year-end round-up, but I did skip the entire month of October, so. —I do have a Big Stupid Idea that I might start chipping away at. And I’ll try to make a point of not dismissing little stuff before I can post it; sometimes big things come from little stuff. —And I mean, 2009 was a pretty good year for blogging, wasn’t it? (Oh, hey, I was poking at Watchmen then, too!)

Like tears in rain.

I miss restaurants, sure, of course, but there’s take-out, which salves at least the most immediate loss (to me, of course.) —You know what I really miss? Busses. I got so much reading done on the bus.

Rain is falling, here in Portland...

but this song, God damn, this song.

—in the palaces of Kings, in the drawing-rooms and boudoirs of certain cities—

Even if these problems could be overcome, other barriers to integration would likely present themselves. Keystone transsexual activists are of generally of [sic] lower socio-economic status, and are probably reliant on their private dwellings for offline meeting. Additionally, while keystone radical deminists generally have homes with reception rooms, transsexual dwellings are probably much smaller (likely amounting to a studio flat or a single bedroom in shared accommodation) making the level of social familiarity required to be invited in unusually high. It is also possible that the private behaviour of transsexuals is so abnormal and morally depraved as to rule out accepting such an invitation [sic sic sic].

As such, no “inner sanctum” discussion has ever been observed, either online or offline. Likewise, no operative has succeeded in forming any form of friendship (let alone an intimate relationship) with a transsexual activist.

This time she went ahead of him and opened a door she felt must be to the kitchen. Light fell on desolation. Worse, danger: she was looking at electric cables ripped out of the wall and dangling, raw-ended. The cooker was pulled out and lying on the floor. The broken windows had admitted rain water which lay in puddles everywhere. There was a dead bird on the floor. It stank. Alice began to cry. It was from pure rage. “The bastards,” she cursed. “The filthy stinking fascist bastards.”

They already knew that the Council, to prevent squatters, had sent in the workmen to make the place uninhabitable. “They didn’t even make those wires safe. They didn’t even…” Suddenly alive with energy, she whirled about opening doors. Two lavatories on this floor, the bowls filed with cement.

She cursed steadily, the tears streaming. “The filthy shitty swine, the shitty fucking fascist swine…” She was full of the energy of hate. Incredulous with it, for she had never been able to believe, in some corner of her, that anybody, particularly not a member of the working class, could obey an order to destroy a house. In that corner of her brain that was perpetually incredulous began the monologue that Jasper never heard for he would not have authorized it: But they are people, people did this. To stop other people from living. I don’t believe it. Who can they be? What can they be like? I’ve never met anyone who could. Why, it must be people like Len and Bob and Bill, friends. They did it. They came in and filled the lavatory bowls with cement and ripped out all the cables and blocked up the gas.

Infiltration into large affinity group meetings is relatively simple. However, infiltration into radical revolutionary “cells” is not. The very nature of the movement’s suspicion and operational security enhancements makes infiltration difficult and time consuming. Few agencies are able to commit to operations that require years of up-front work just getting into a “cell” especially given shrinking budgets and increased demands for attention to other issues. Infiltration is made more difficult by the communal nature of the lifestyle (under constant observation and scrutiny) and the extensive knowledge held by many anarchists, which require a considerable amount of study and time to acquire. Other strategies for infiltration have been explored, but so far have not been successful. Discussion of these theories in an open paper is not advisable.

Fully automated hauntology.

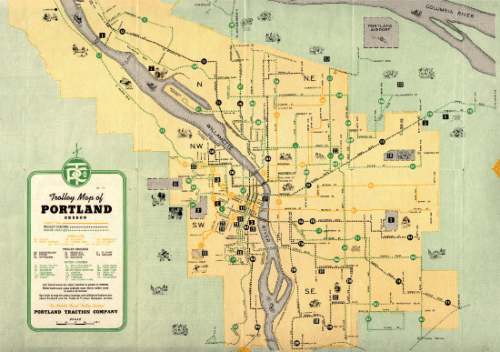

I do wonder how authors dealt with the memories of cities and the ever-changing fabric of their ever-present selves in the days before we had Google’s Street View, and specifically now the history slider, letting you slip back and back to see what it looked like the last time one of those camera-mounted cars wandered these same streets, or the time before that: oh, look! you say, cruising past your own house on the monitor of the computer within it. Our car was parked right out front that day. What a curious sense of pride. (—If I were in my office instead, I might look up to see the enormous map of Ghana on the wall, and decide to walk the streets of Accra for just a few minutes to clear my head; we can do that, sort of, now.) —But there are costs, and slippages: this morning I was trying to find an appropriate bus stop to loiter at, needing to catch the no. 6 bus up MLK to (eventually) Vanport; I was reminded they’re building a building there now, where once had only been a parking lot, and a Dutch Bros. coffee cart, and happened upon a view of the construction site from April of 2019, when the first floor had been set in concrete and rebar, waiting for six more wood-framed storeys to balloon above it, but I stepped sideways, into another stream of views, that only offered September or June 2019 (the wood having bloomed now clad in brick, or what passes for brick these days) or August 2017 (the lot, the coffee, the light already different, as if lenses have changed enough since then to be noticed), and so here I am, with a morning spent bootlessly wandering over and over the same corner and streetfront, trying to find the precise spot from which I can once more catch that bygone glimpse of April, of last year.

Half a million words.

So the thing-that-argues (the argument itself being scattered in pieces all over the pier)—and, I mean, wait a minute. Maybe—maybe it’s about time, when you’ve amassed a corpus like this—

—maybe it’s time to stop being quite so self-indulgently coy?

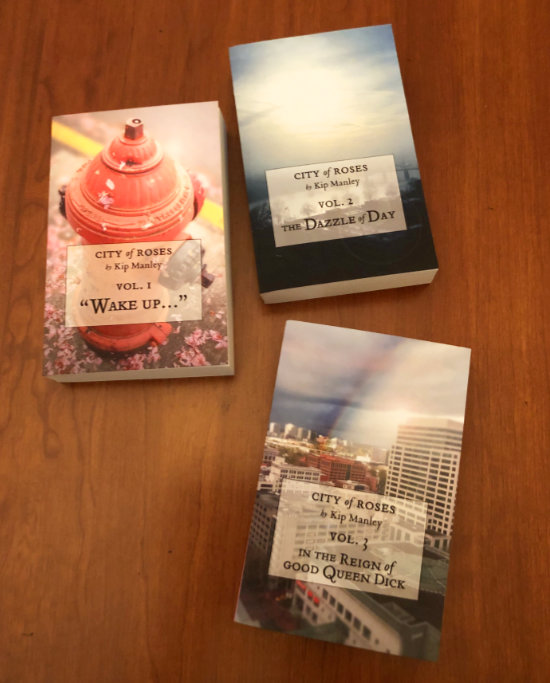

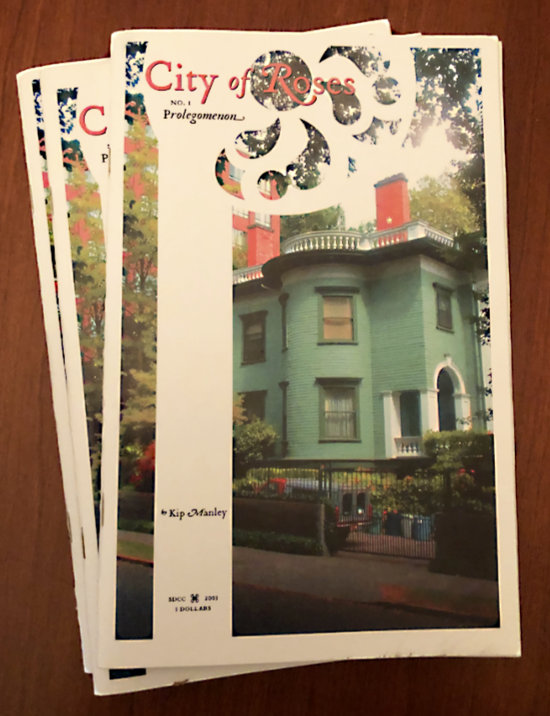

So the epic (I think we can call it an epic, now, right?) just passed a milestone: with the release of no. 34, the first chapbook of vol. 4, —or Betty Martin (and here’s one of the problems of the epic: the cruft needed to identify exactly where you are in the flow of the thing)—anyway, the epic just passed the half-million word mark. These three book-shaped objects—

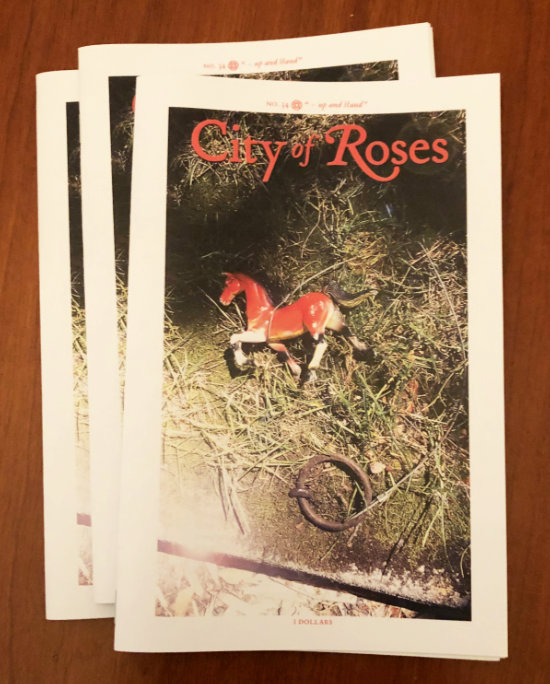

—plus this slender, unassuming ’zine (appearing in installments Monday-Wednesday-Friday for the next two weeks)—

—add up to 511,358 words, according to this device on my desk here (minus the furniture of introductions and forewords, of course): why, that’s just over 29% of a Song of Ice and Fire!

—Anyway. Forgive me my indulgences, as I forgive those who indulge me; I just figured the occasion ought to be marked, somehow. I’ve been at this a while. There’s a whiles yet to go.

Don dances in the wet street.

Grad School Vonnegut got to Timequake, and of course to Trout’s Credo:

You were ill,

but now you’re well again,

and there’s work to do.

But—and I’m not nearly fluent enough in British fashion or football hooliganism or recent trends in international capital to unpack everything that’s going on in this ad; still—

You are as you have been,

but the world will never be again—

and yet, there’s dancing to be done.

I’m reminded of something I wish I could find, that Geoff Ryman said about his novel, The Child Garden, but it was some time ago, and I can’t remember the words; still, the gist of it was that dystopias are usually limited because they presuppose a here-and-now: as cautionary tales, they’re presented as problems for their protagonists to solve, worlds to be saved, not lived in, and how exhausting is that? How much better would it not be to write to draw to film to record a story about just living in the world as whatever it is it might be?

I know, I know: saving is what misers do. But I don’t know.

If it doesn’t happen, what we’ll see is a variety of predictable partial responses: unevenly distributed technological innovation, and cultural forms of quietism and accommodation. If we can’t really do anything collectively, people will try to live with disaster, internalizing and riding it rather than trying to change it.

Failsons & November criminals.

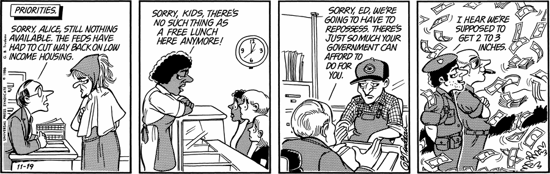

O frabjous day! Callooh! Callay! It’s the thirty-fourth anniversary of my radicalization, which I can date with such alacritous precision due quite simply to the fact that it in turn is due to a comicstrip:

It was more of a straw and a camel’s back than a short sharp apocalypse: and it’s not like there wasn’t then or isn’t even yet a long ways left to go (not too much later, I found myself at Oberlin, tut-tutting my fellow students’ embrace of John Brown, whom I, ’Bama boy that I am, took, at the time, to be a righteous but nonetheless terrorist)—but, but: I’d wet my feet in a Rubicon. We could’ve been making the world a better place. We chose not to.

Thinking about how much of what was then recent history I learned back in the day not from lectures and classwork, from school, but from nipping off to the library to dig through Doonesbury collections, augmented by archives of Feiffer and Herblock and, well, yes, MacNelly, one must have balance, one supposes.

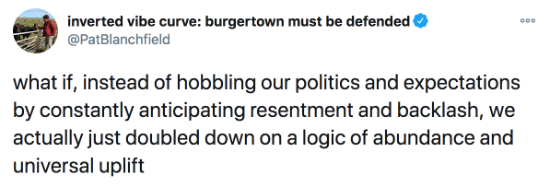

Thinking about that because of what Pat Blanchfield says in this snarkily “Bruckheimer shit” walkthrough of the latest instantiation of the (wildly popular) (wildly deranged) Call of Duty franchise—

A quarter of a billion people, whatever, have played these games, um, and so many American men do, one of the few ways a lot of people ever learn anything even resembling, like, the existence of this history, like, for example, like, in the last game, we were in Angola, is through these games.

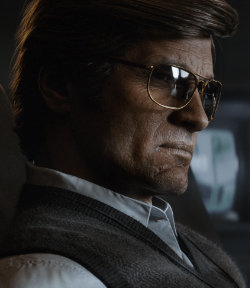

Sobering, and not just for the ideology the games are steeped in, Dolchstoßlegending this or that regrettably unpleasant incident from Yankee history into thrillingly deniable covert ops that left the world, our world, far better off than it otherwise could’ve been, and don’t you forget it— not just the ideology, but also the technique: the hilariously toxic masculinity (when have you ever seen Robert Redford looking so ghoulishly rugged?), the conversational hooks and moral dilemmas drawn from grade-Z B-movie scripts (to say nothing of those meticulously recreated backlot backdrops), all the eye-snagging tics and dialects of body language drawn from deeply uncanny valleys, and touches like the robustly verbose commanding presence of President Dutch, who marches into an expository cutscene (after a prologuizing Gladio massacre) ahead of an anachronistic shaky cam—this isn’t the Reagan to be found in anything close to any actual history this world came up out of; this is a Reagan from a Saturday Night Live skit—

not just the ideology, but also the technique: the hilariously toxic masculinity (when have you ever seen Robert Redford looking so ghoulishly rugged?), the conversational hooks and moral dilemmas drawn from grade-Z B-movie scripts (to say nothing of those meticulously recreated backlot backdrops), all the eye-snagging tics and dialects of body language drawn from deeply uncanny valleys, and touches like the robustly verbose commanding presence of President Dutch, who marches into an expository cutscene (after a prologuizing Gladio massacre) ahead of an anachronistic shaky cam—this isn’t the Reagan to be found in anything close to any actual history this world came up out of; this is a Reagan from a Saturday Night Live skit—

—(and also, yes, all the guns and the shooting and the extreme violence and all that stuff). —It’s, and I use the term advisedly, a cartoon: both in the sense that it’s deliberately, expressively, ruthlessly simplified, drawing power from its crudely broad strokes, and also in that it’s deliberately, ostensibly disposable: a work of paraliterature no one could ever take seriously, c’mon, a staggeringly elaborate, kayfabily po-faced act of kidding-on-the-square, a deniable covert op that leaves us thinking all unawares with precisely what it is we’ve been laughing at, for however long we’ve been twiddling our thumbs at the flatscreen.

Anyway. Down with all Commander Less-Than-Zeroes, wherever they might be found. Give me a November criminal any goddamn day.

Two-score and a dozen years ago.

Monday’s child is fair of face, they say, so hey—I got that going for me.

When the operation of the machine becomes so odious.

“Everything that is happening to the men who knew Taylor is happening because prosecutors do not want to hold Taylor’s murderers accountable. This is what the system does when it does not want to secure a conviction. Prosecutors themselves try to poison the jury pool against their own case, creating avenues of doubt before any trial process gets going. They try to impugn the character of people who will have to be witnesses for the prosecution. They try to avoid doing forensic research so that they have no ‘hard’ evidence to present to the jury, should it come to that. And they try, desperately, to get anybody to speak out against the victim so the defense can use those statements against the prosecution at trial.” —Elie Mystal

Our Americans.

“The police officers stepped out of the room for just a brief moment, just outside the door. And I told the physician like, ‘Hey, I work here, I’m a nurse here.’ And that shifted everything.” —OHSU nurse and volunteer medic Tyler Cox.

Loudly with the quiet part.

Accordingly, I urge you to prioritize public safety and to request federal assistance to restore law and order in Portland. We are standing by to support Portland. At the same time, President Trump has made it abundantly clear that there will come a point when state and local officials fail to protect its citizens from violence, the federal government will have no choice but to protect our American citizens.

This, from illegally Acting Secretary Chad F. Wolf, to Ted Wheeler, desperately unpopular mayor of a city that’s been on fire for decades, which is news to most of us who live here, letmetellyou. —That “our” American citizens is a nice fucking touch, isn’t it? Let America’s Sheriff, David Clarke, make it abundantly fucking clear:

The question is when is government going to do something? Inaction is not a plan. You know what happens with inaction? People take the law into their own hands. Government is leaving them no choice. No choice. I don’t advocate for some of the stuff that’s starting to happen, but I am certainly done—I am through with condemning it. I’m done with that.

I’m just telling people, “Hey, you’re on your own.” Think about it, have a plan. Act reasonably. You have to act reasonably. Then you’re going to have to articulate what you did afterwards. But you can’t have government officials and law enforcement executives telling people, “Do not take the law into your own hands.” Well, you’re forcing them to!

And—wait, I’m sorry, but the utterly gratuitous comma splice from our Acting Secretary is just grating my eyeballs, and Christ, you know me, I’m the king of comma splices, but those two independent clauses, “President Trump has made it abundantly clear,” yes yes, and “the federal government will have no choice,” I mean, for fuck’s sake, those two don’t even articulate coherently as one sentence after another in a paragraph, much less as clauses enjambed by a comma! At long last, you murderous franchisees, have you no decency?

—Sorry. Where were we? —Ah, yes: the vicious fuckwad in the back of the pickup truck with the gun is one of “our” Americans, those of us he’s shooting at are by definition not, and he won’t even have to worry about articulating what he did afterwards, because the Portland Police Bureau did fuck-all to stop him, leaving him more than well enough on his own.

Hey. At least we’ve got Paris.

Ecophage.

Another way to look at their downward spiral is as a parable of a housing market that is not primarily intended, or even incentivized, to actually house people. “We don’t finance housing in this country,” says Ron Shiffman, a city planner and tenured professor at Pratt’s School of Architecture. Instead, housing serves as a “financing tool.” The market encourages buyers, whether Saudi princes or the owners of yoga studios, to treat homes like banks, as places to put their money, whether or not they actually live in them. It also motivates developers to build luxury properties with the highest returns, housing fewer residents. In New York, the pandemic brought the dangers of this system painfully to light, as mass economic devastation made many people, even landlords like Gendville and Brooks-Church, suddenly desperate for real-time shelter. “The housing market isn’t meeting the needs of people who are working, who are living, in New York,” Shiffman says. Brooklyn’s runaway success, it turns out, was built on an economic disparity so intense that it has created a microgeneration of gentrifiers like Brooks-Church and Gendville who are now being priced out themselves.

All those generic slender needles you see piercing the New York skyline, more and more of them every time you used to fly in to Newark, or JFK, in the Before Times, gnomons sweeping shadows over more and more of the streets you used to walk, those towers, every single one of them, are not towers; no one lives in them, as you or I understand living. They’re safety deposit boxes, for offshore billionaires who’ve never thrown parties in those penthouses—or worse, unthinkingly assembled byproducts of the financial eructations of distant hedge funds. (At least billionaires can dream of bit parts in the next Furiously Fast Impossible Mission.) —Have you noticed? Watching the teevee? All the shows filmed in the City: how easily, and how often, now, they can film on location, in great buildings with spectacular views. Somebody’s got to do something with all those empty floors.

Or used to have to have done, at least. Before.

“Plants” with “leaves” no more efficient than today’s solar cells could out-compete real plants, crowding the biosphere with an inedible foliage. Tough omnivorous “bacteria” could out-compete real bacteria: They could spread like blowing pollen, replicate swiftly, and reduce the biosphere to dust in a matter of days. Dangerous replicators could easily be too tough, small, and rapidly spreading to stop—at least if we make no preparation. We have trouble enough controlling viruses and fruit flies.

Among the cognoscenti of nanotechnology, this threat has become known as the “gray goo problem.” Though masses of uncontrolled replicators need not be gray or gooey, the term “gray goo” emphasizes that replicators able to obliterate life might be less inspiring than a single species of crabgrass. They might be superior in an evolutionary sense, but this need not make them valuable.

The gray goo threat makes one thing perfectly clear: We cannot afford certain kinds of accidents with replicating assemblers.

La même chose.

“Portland is a place where rich ones run away to settle down and grow flowers and shrubbery to hide them from the massacres they’ve caused. Portland is the rose garden town where the red, brown, blackshirt cops ride up and down to show you their finest horses and saddles and gunmetal.” —Woody Guthrie

Regrets, I've had a few.

Most notably, today, at this moment, the fact that I went the one way, when I coulda gone the other, which, granted, okay, kinda a foundational, even definitional experience of regret, sure, but anyway, back when we were tussling over questions of belief («belief» belief BELIEF) and the foundations, the definitions of fantasy and SF, I mean, I kinda wonder what might've happened if I’d leaned harder into the notion that SF is an argument with the universe, that fantasy is a sermon on the way things ought to be, because an argument’s a tool, a machine of words and logic that might be deployed with whatever passion or skill you care to bring to bear, or don’t, and so matters of “belief” are almost incidental (almost)—but a sermon, a real pulpit-pounding barn-burner of a stem-winder, hell, that pretty much requires belief: but not belief as in some positivist notion that what one posits is what one takes to be “real” (I once told my paramour at the time of how, during that first acid trip, I’d heard f--ry fiddles playing as streetlight scraped over frozen grass; but really? she asked, did you really hear them? Really? —We broke up sometime later); no: belief as in conviction, as in the indisputable fact that one knows the way things ought to be, and because the sermon ought to be, it necessarily addresses a world that isn’t: a belief, therefore, in what can’t be believed. —You want it to be one way. You want it to be one way, but it’s the other way. QED.

The visible world is merely their skin.

Altogether elsewhere, an interlocutor described the work of someone whom I haven’t read, for reasons, as, and I quote, “filmic and competent and all surface. And all the epigraphs only makes things worse,” and I know, I know, it has nothing to do with me, per se, but still: I felt so seen. —I do wonder, sometimes, as to how and why and the extent to which I’ve decided that the thing-I-do-with-prose should be so devoted to things prose is not supposed to do, but it’s like they say: anything worth doing is worth doing backwards, and in heels. [Strides off, whistling “Moments in the Woods.”]