God, hes left as on aur oun.

“—I pray you, as I pronounced it to you, trippingly—”

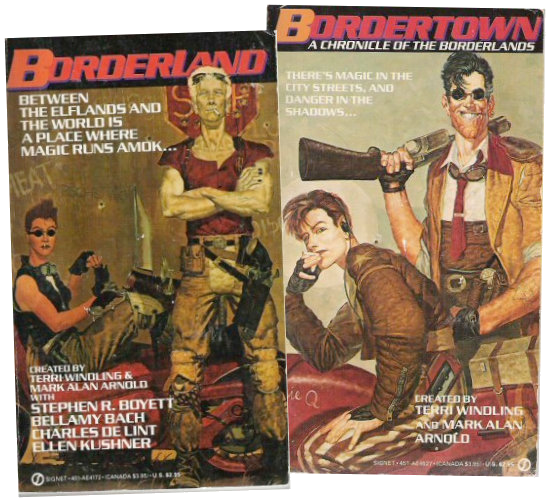

While I was poking about, looking for what I’d said back in the day about ostranenie and the unheimlich (mostly I was trying to remember that push-me-pull-you refrain, oh I see, oh I get it, which I didn’t end up using, but make what you will of the fact I forgot), anyway, I ended up over at the Mumpsimus, contemporaneously, and saw a link in a linkdump that said, “Elves killed by punk rock,” and of course I clicked on it. —Wouldn’t you?

Magic—or more precisely, the “magical”—was one of the first casualties of punk rock. As guitar solos contracted and song structures were shaved to a stump, with amazing speed we lost our dragons, our druids, our talking trees—the whole seeping, twittering realm of the fantastic was suddenly banished, as if by a lobotomy. It survived, lurkingly, in the lower realms of heavy metal and Goth, but no one would ever again fill a stadium by singing about Gollum, the evil one. Punk rock had killed the elves.

And, well, I mean, you know what I’m gonna say about that.

Magic will not be contained. Magic breaks free. It expands to new territories, and it crashes through, barriers, painfully, maybe even dangerously, but, ah, well. There it is. Magic, uh, finds a way.

—And we can quibble about category errors and gestures and deeds and what does or doesn’t count as punk rock to a high school kid in 1987, casting about for whatever wonder-generating mechanisms are in reach, and maybe it’s less punk and more sludge, I don’t know, you can head over to YouTube to listen to the subjects of this fifteen-year-old review for yourself, but mostly the reason I’m mentioning this at all is something from the end of it, said by Dead Meadow’s singer and guitarist, Jason Simon. “These writers,” he says, “to me—”

(—he’s talking about the writers that the writer says he said are his favorites, and these writers of course are folks like H.P. Lovecraft, Algernon Blackwood, William Hope Hodgson, and Arthur Machen—)

These writers, to me, are just a celebration of pure imagination. And it seems like the imagination is suffering these days—so many images coming at you, so shallow and so fast. We’re trying to create songs with some space in them, some imaginative space, to give people some room.

It’s an importantly counterintuitive point, about how the imagination suffers under the onslaught of imagination, and how absolutely vital it is to give the audience some credit.