Half a million words.

So the thing-that-argues (the argument itself being scattered in pieces all over the pier)—and, I mean, wait a minute. Maybe—maybe it’s about time, when you’ve amassed a corpus like this—

—maybe it’s time to stop being quite so self-indulgently coy?

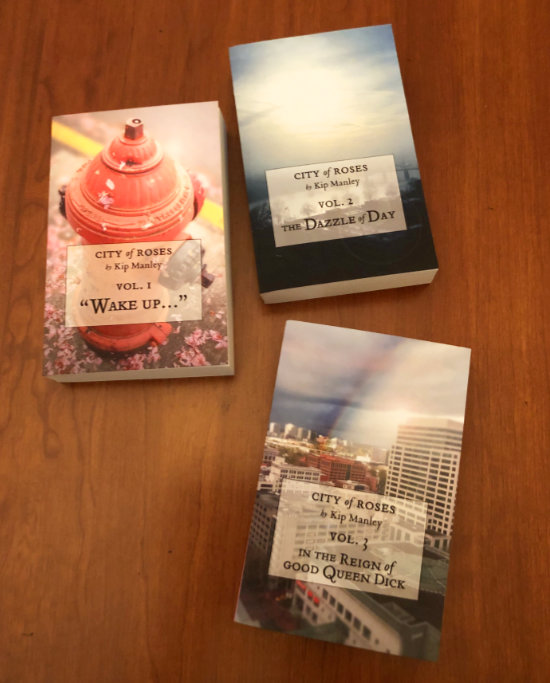

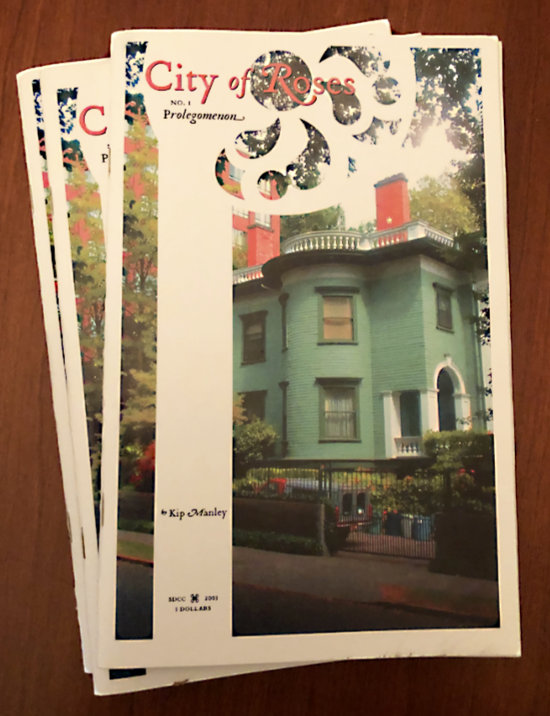

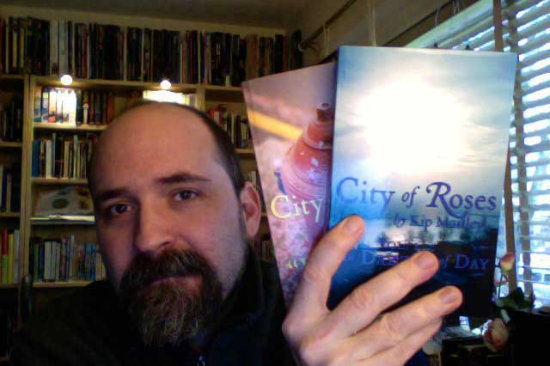

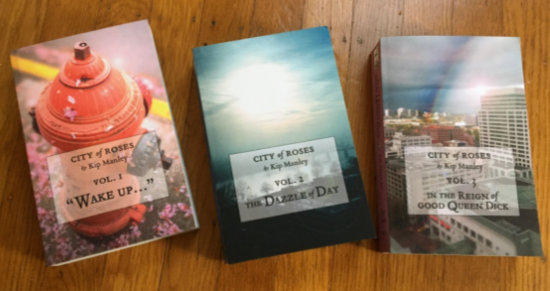

So the epic (I think we can call it an epic, now, right?) just passed a milestone: with the release of no. 34, the first chapbook of vol. 4, —or Betty Martin (and here’s one of the problems of the epic: the cruft needed to identify exactly where you are in the flow of the thing)—anyway, the epic just passed the half-million word mark. These three book-shaped objects—

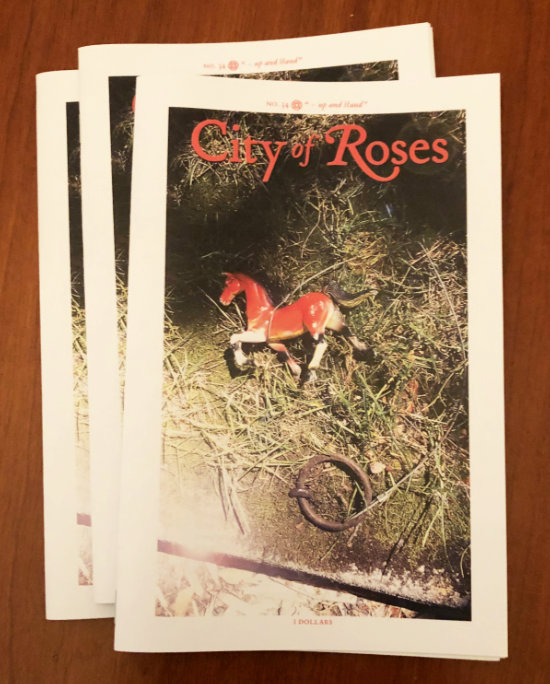

—plus this slender, unassuming ’zine (appearing in installments Monday-Wednesday-Friday for the next two weeks)—

—add up to 511,358 words, according to this device on my desk here (minus the furniture of introductions and forewords, of course): why, that’s just over 29% of a Song of Ice and Fire!

—Anyway. Forgive me my indulgences, as I forgive those who indulge me; I just figured the occasion ought to be marked, somehow. I’ve been at this a while. There’s a whiles yet to go.

Two-score and a dozen years ago.

Monday’s child is fair of face, they say, so hey—I got that going for me.

The visible world is merely their skin.

Altogether elsewhere, an interlocutor described the work of someone whom I haven’t read, for reasons, as, and I quote, “filmic and competent and all surface. And all the epigraphs only makes things worse,” and I know, I know, it has nothing to do with me, per se, but still: I felt so seen. —I do wonder, sometimes, as to how and why and the extent to which I’ve decided that the thing-I-do-with-prose should be so devoted to things prose is not supposed to do, but it’s like they say: anything worth doing is worth doing backwards, and in heels. [Strides off, whistling “Moments in the Woods.”]

Manichæan.

I might’ve made a mistake when I began the thing-that-argues. —Because I could not hear myself constantly and on a regular basis referring to Jo as a white woman (or, God forbid, a White woman), it would not be fair to single out Christian, say, by referring to him as a Black kid, or to Gordon as a black man.

Because I would not mark all of them, I could not mark any of them, so as to mark them all the same. The logic’s ineluctable.

But, you know. Logic.

It’s not just a matter of black, or Black, and white, of course. —How would you go about marking Ellen Oh? Would you say she is Korean? Even though she was born in Alabama, and most of her family hasn’t lived in Korea for a couple generations now? (Can you specify to any useful degree the differences in appearance between all possible individuals whose forebears might at one point have been sustained by that mighty peninsula, and the appearances of anyone, everyone else, that would render such a marker immediately perceptible, and adequately useful?) —You might perhaps think “Asian” to be an acceptable compromise, as a marker, but look for God’s sake at a map: Asia’s everything east of the Bosporous. How staggeringly varied, the appearances of everyone from there, to there! Worse than no mark at all, distorting marker and marked, and to no good or necessary purpose.

(The Ronin Benkei was flatly Japanese, even though Farrell was much too polite ever to notice more than a few echoes of classical Japanese manners in the gestures of Julie Tanikawa, whom he never heard swear in Japanese, except that once, for all that she spoke it as a child, with her long-dead grandmother.) (And as for Brian Li Sung—oh, but comics have their own markers, at once far more persnicketily precise, and yet so roomily ambiguous, and I’ve said too much.)

It’s not that the characters aren’t marked at all, of course: just not with such totalizing, reductive, contingent signs. Everyone’s described in much the same manner: their clothing, the way they carry themselves, their hair, how they say the things they say, the way the light hits them (the visible world being merely their skin)—the hope, of course, being that these pointilist details will accrete into a portait in the reader’s mind—inaccurate, perhaps, at the start, but resolving over time toward something more and more like what’s intended. (—Or, to be precise, what’s needed to make what’s intended work; this is imprecise stuff, this work, but really, think about it: how could even a single person, that is so large, ever fit within a book that is so small?)

But what does such a cowardly refusal on the part of the narrative voice, to plainly mark what any other medium would’ve plainly marked, by virtue of not being limited to one word set after another—what does this do to a reader’s relationship with the portrait they’ve been assembling when it suddenly must drastically be rearranged, after thousands upon thousands of those words? (I mean this at least is gonna hit a bit different than Juan Rico offhandedly clocking himself in a mirror on page two hundred and fifty.)

But let’s turn it around a minute: is it my fault if you didn’t assume from the get-go that an un(obviously)-marked character in a novel written by a white man, in a rather terribly white idiom, set in one of the whitest cities in the country—is it on me if you’re the one who assumes, before you’ve been told, that this character’s clearly white?

My own take on the question of the moment, or at least of the moment when I began sketching this out (though I’ve been thinking about something like it for a while now; it might’ve been the foreword of the third book, had anything coalesced in time)—my own take is not unlike what’s laid out by Angus above: because I would not dignify the constellation of revanchist grievances, the cop’s swagger and the supervisor’s sneer, that make up the bulk of what passes for the race I could call my own—because I would never capitalize that—well. Logic demands. Right?

But it’s ad fastidium, is what it is. —I could bolster it with an argumentum ad verecundiam, by turning to what Delany’s said, on his own perspective on the subject, bolstered in turn by Dr. DuBois’:

—the small “b” on “black” is a very significant letter, an attempt to ironize and de-transcendentalize the whole concept of race, to render it provisional and contingent, a significance that many young people today, white and black, who lackadaisically capitalize it, have lost track of—

Oh, but that was written in 1998, which is further away than it seems. Which is not to say anything’s changed, good Lord, I wouldn’t know, I only ever had breakfast the one time with the man, and we mostly talked about Fowles. But then, there’s this, from 2007, or 2016, depending:

“And those aren’t races. Those are adjectives of place—like Hispanic. And Chinese. Caucasians are people from the area in and around the Caucasus Mountains, which is where, at one time—erroneously—white people were assumed to have originated.”

“Latino..?”

“And that refers to the language spoken. So it gets a capital, like English and French. There is no country—or language—called black or white. Or yellow.”

But when he told this to a much younger, tenure-track colleague, the woman looked uncomfortable and said, “Well, more and more people are capitalizing ‘Black,’ these days.”

“But doesn’t it strike you as illiterate?” Arnold asked.

In her gray-green blouse, the young white woman shrugged as the elevator came—and three days later left an article by bell hooks in Arnold’s mailbox—which used “Black” throughout. He liked the article, but the uppercase “B” set Arnold’s teeth on edge.

And yes, it’s much the same argument! But it sits very differently, with different emphases and outcomes, when it comes from the mouth of Arnold Hawley, such a very fragile man—not Delany’s opposite, no: but still: his reflection, seen in a glass, darkly, as it were.

(Everyone knows there is no country called black, or language. What capitalizing the B presupposes is: maybe there is?)

But my own take on whether to capitalize “black” has no bearing on the thing-that-argues—in part because I’ve short-circuited it entirely, yes, but also and mostly because none of the people in it give a damn what I think, nor should they: the thing-that-argues, when it turns its attention to any such matter, should only ever care what it is they think, and how, and why: Christian thinks of himself as a Black man, for all that Gordon sees him as a black boy; H.D. sees herself as a Black businesswoman, concerned as she is with Black businesses; Udom, the new Dagger, still thinks of himself as from Across-the-River, though he knows most everyone these days sees him as one of the Igbo; Zeina, the new Mooncalfe, would probably say she’s black, or crack a bleak joke about Atlantis, and drowned mothers-to-be, or maybe she’d punch you, I don’t know; and Frances Upchurch (though that is not her name) would tell you exactly what you’d think she would, and never you’d know otherwise. —And each of them must be able to believe what they believe, to fight for it, or change their minds, without ever having to worry about some quasi-objective narrative voice thinks maybe it knows better blundering up to flatly gainsay them, this white voice in a terribly white idiom telling each and every reader that this was said by a Black man, or that was thought by a black woman, tricking these readers, every one, into thinking they maybe know what the author thinks—or worse, what the thing-that-argues thinks—and thus, what ought to be right, and further thus, who should be, could be, must be wrong. —And this understanding extends to all things.

(The narrative voice of Dark Reflections does not capitalize “black,” when referring to jeans, or to people, and so we can think we know what the author thought just a few years ago, or at least his copyeditor.)

So maybe I made a mistake at the start of it all. But there was thought behind it? At the start? Reasons to have done it, not that those are a guarantee of any God damn thing. —Maybe I’d do it differently, I were setting out today. Maybe I still regret using quotations marks, or writing it down as “Mr.” instead of “Mister.” But here we are.

There is a strength in writing as a fool, you do it right. Talking outside the glass. The room, that negative space affords, for the characters, for the story, for the readers (or so I tell myself, but I am a fool)—there’s power, in setting a taboo like this. You may not talk inside the glass, but still: you spill enough words, the shape of the glass can start to be made out.

Move fast; break things.

One is not unaware of a certain disgruntlement in certain quarters regarding a certain operation to which one has recently bound oneself; one looks at the one hand, one looks at the other, one manages a shrug of a bromide, life is compromise, I don’t know. It’s another of those situations where the structure is such that your choice or my choice can’t make a dent in the structure, but it’s all the structure will afford any one of us. They’re burning the postal service to the ground to steal an election—you maybe wanna buy a book? Could help pass the time until a general strike’s declared.

More numbers.

So I sold a copy of the new book through Amazon a couple-few days ago, for eighteen dollars. —I made forty-three cents.

Publishing is hard, y’all.

Despite recent movements advocating pushback against Amazon, most people in the United States maintain a favorable view of Jeff Bezos’ “everything store.” Peter Hildick-Smith, president of book audience research firm Codex, says that this includes most people who frequent independent shops; just over three-quarters of that cohort also use Amazon, at an average of five times a month, according to a 2019 survey. Even among bibliophiles, Hildick-Smith says, “It’s not as if everybody’s saying, ‘Gosh, I really don’t like Amazon. I don’t shop there’.” The result? “A very skewed market.”

When I first started putting this thing out in books (as opposed to words, or ’zines), I went with CreateSpace, because it was there, and because you could give them a PDF and some money and a couple days later you’d have a book-shaped stack of paper, neatly bound—

—which was a neat-enough trick, even if the paper’s a whit too glossy, and the cover a touch too stiff, to feel quite right in the hand, and every now and then you get a copy with sixty some-odd pages of the Petrisin Guide to Taking CLEP Exams stuck in the middle.

But even then, CreateSpace was being bound ever more tightly to Amazon, and now it’s been utterly subsumed, it’s gone; it’s nothing but Kindle, all the way down. —And if Hildick-Smith had a hard time finding bibliophiles who don’t like Amazon, well, he didn’t talk to very many booksellers, or librarians.

had a hard time finding bibliophiles who don’t like Amazon, well, he didn’t talk to very many booksellers, or librarians.

If you spend eighteen dollars to buy the old CreateSpace Amazon paperback edition of “Wake up…”, published by and distributed by and pretty much only sold by Amazon, well, Amazon pays me four dollars. I can buy an author’s copy for six dollars and eighty cents, so we’ll take that as their basic cost to print; eighteen minus four minus six point eight leaves seven dollars and twenty cents for Jeff Bezos’ pocket.

The numbers for the new, Supersticery Press edition shake out a bit differently: published by me, printed by IngramSpark, distributed by Ingram, available to be sold by just about anyone who buys books wholesale from Ingram. The wholesale price is forty-five percent of the list price, or seven dollars and sixty-five cents. It costs seven dollars and four cents to print a copy; IngramSpark then credits my account with sixty-one cents. Profit!

The wholesale price is forty-five percent of the list price, or seven dollars and sixty-five cents. It costs seven dollars and four cents to print a copy; IngramSpark then credits my account with sixty-one cents. Profit!

But there’s fifty-five percent of the list price left over: nine dollars and thirty-five cents. And that goes to whomever sells the book. Me, for instance, if you buy it direct. Your local bookstore, which you can do through IndieBound, assuming your local bookstore participates—even if they don’t have it on the shelf when you order. —Or, y’know, Jeff Bezos, I suppose. If you wanted.

Or if you buy a copy through Bookshop.org—which you can do with the click of a mouse or a tap on the screen—ten percent of the list price, or a dollar seventy, goes into a pool that every six months gets divvied out to bookstores in the American Booksellers Association; another dollar seventy goes to whomever gave you the link to Bookshop (like me, if you buy through this). (If it’s an ABA bookstore that gives you the link, they get twenty-five percent, not ten: four dollars and twenty-five cents.) —And you’ll notice you’re not paying full price, which is another thing a retailer can do with that fifty-five percent.

(Of course, there’s still anywhere from two dollars and four cents to four dollars fifty-nine cents going into Bookshop.org’s pockets, but they have expenses, and it’s okay, they’re a B-corp, and also capitalism.)

I’ll probably keep the Amazon editions around; I’m mildly amused by the mild confusion, and anyway to shut them off I’d have to figure out which website I’m supposed to log into now and what my password was or is or ought to be, and who has the time. —What’s also amusing to me, with Amazon, is of course they carry the new editions, of all three books (they carry everything Ingram distributes, because why not), but: you wouldn’t know it from search results, or looking at my Amazon author page. You can only find the Amazon editions for the paperbacks of the first two, but! Amazon makes more money off the editions that aren’t theirs: two dollars and fifteen cents more, per copy.

Well, anyway. I chuckled. Mordantly, but.

Speaking of self-publishing—

—as we were:

I’ve finally managed to secure test printings of paperbacks from a print-on-demand shop that isn’t wholly owned by the largest and hungriest and most endangering river-system in the world, and holy cats, they are beautiful? They sit in the hand just right and the paper, the paper has this rough-hewn pulpy feel like a mass-market paperback you picked up from a spinner rack instead of that glossy slick you get from so many self-published books like too many (wonderfully, eminently playable) small-press RPGs. —It only took me 22 business days, plus shipping, to do it, since apparently what with the raging pandemic and all there’s been something of an impact on our ability to order and print and place books on demand, but hey.

So! You can certainly order them through me, which would make me ineffably happy, but your local library, or an independent bookstore, might also appreciate the nod, and anyway, them? Being plugged into the way things are? Might move it all along a little faster, because, what takes me, the publisher, 22 business days to deliver, the river insists would only take 11 to 17.

For, indeed, the watch ought to offend no one, and it is an offence to stay anyone against their will.

A socially distanced rally is a strange thing: but Neysa Bogar read Audre Lorde, and Renee Manes carried a sign that said Public Defenders Telling You That Cops Lie For 50+ Years, and even though we couldn’t hug each other, or rub shoulders, the energy was righteous, and the chants, though slightly muffled, still rang out, and one of those chants was DEFUND THE POLICE, and that’s the strangest thing, to me, at least, about the past mad wild upsetting unsettling enraging couple of weeks? —That this idea, that seemed an uncertain step too far when I first encountered through links to Mariame Kaba‘s Twitter feed, that firmed up underfoot as I read about it and sat with it and thought through it until I came around to the point I could say, yes, we must abolish prisons; yes, we must defund the police, all of them, right down to the ground; yes, we have no choice but to do the work to build a world where life is precious, so that life might be precious: that this wild mad desperately necessarily eutopian idea is suddenly lurching into view through the Overton window, to the point that John Oliver can do a whole dam’ show about it, on HBO.

Defund the police.

But for those who still find themselves clung to the notion of reform (radical, to be sure; meaningful; even bold), or those whose abolitionary imaginary only reaches to medieval Iceland—it occurs to me, that Dogberry’s advice to the watch might well prove an excellent basis for a retraining program for our thin blue lines. —Anyway, it’s a start. Policing delenda est.

The most relevantly framed.

DOGBERRY

This is your charge: you shall comprehend all vagrom men; you are to bid any man stand, in the Prince’s name.SECOND WATCH

How, if a’ will not stand?DOGBERRY

Why, then, take no note of him, but let him go; and presently call the rest of the watch together, and thank God you are rid of a knave.VERGES

If he will not stand when he is bidden, he is none of the Prince’s subjects.DOGBERRY

True, and they are to meddle with none but the Prince’s subjects. You shall also make no noise in the streets: for, for the watch to babble and to talk is most tolerable and not to be endured.SECOND WATCH

We will rather sleep than talk: we know what belongs to a watch.DOGBERRY

Why, you speak like an ancient and most quiet watchman, for I cannot see how sleeping should offend; only have a care that your bills be not stolen. Well, you are to call at all the alehouses, and bid those that are drunk get them to bed.SECOND WATCH

How if they will not?DOGBERRY

Why then, let them alone till they are sober: if they make you not then the better answer, you may say they are not the men you took them for.

The most renowned.

SECOND WATCH

Well, sir.DOGBERRY

If you meet a thief, you may suspect him, by virtue of your office, to be no true man; and, for such kind of men, the less you meddle or make with them, why, the more is for your honesty.SECOND WATCH

If we know him to be a thief, shall we not lay hands on him?DOGBERRY

Truly, by your office, you may; but I think they that touch pitch will be defiled. The most peaceable way for you, if you do take a thief, is to let him show himself what he is and steal out of your company.VERGES

You have been always called a merciful man, partner.DOGBERRY

Truly, I would not hang a dog by my will, much more a man who hath any honesty in him.VERGES

If you hear a child cry in the night, you must call to the nurse and bid her still it.SECOND WATCH

How if the nurse be asleep and will not hear us?DOGBERRY

Why then, depart in peace, and let the child wake her with crying; for the ewe that will not hear her lamb when it baes, will never answer a calf when he bleats.VERGES

’Tis very true.DOGBERRY

This is the end of the charge. You constable, are to present the Prince’s own person: if you meet the Prince in the night, you may stay him.VERGES

Nay, by’r lady, that I think, a’ cannot.DOGBERRY

Five shillings to one on’t, with any man that knows the statutes, he may stay him: marry, not without the Prince be willing; for, indeed, the watch ought to offend no man, and it is an offence to stay a man against his will.VERGES

By’r lady, I think it be so.DOGBERRY

Ha, ah, ha! Well, masters, good night: an there be any matter of weight chances, call up me: keep your fellows’ counsels and your own, and good night. Come, neighbour.SECOND WATCH

Well, masters, we hear our charge: let us go sit here upon the church bench till two, and then all to bed.

The most generously apportioned.

Two of Swords (reversed).

Light the candle, draw the card. (I’ve switched from the Bad Girl Tarot to the Carnival at the End of the World.) Tweak a sentence or two, by which I mean take a word out, then put it back. I’ve written five percent of the next first chapter is one way to put it, but another way is to point out most of those words are an opening I’ve discarded, or at least set aside to be repurposed later. Plunge the coffee. Log into the other machine, the work machine, and let the various databases and distance-working tools—overstressed by the demands of an entire segment of the national economy suddenly working from their couches—reset and resynch and restore themselves in the relative quiet calm of four in the morning. Update all the lists of everyone we’ve been able to find so far, folks who might just with patient bureaucratic chipping and exquisitely phrased arguments have a chance to be pried free from federal custody before the virus catches fire in this facility, or that. (It’s already caught fire.) Look up when the daughter’s alarm goes off (sweetly artificial birdsong) and start to think about what can be made into breakfast. Adjust another word. —There’s this, written a couple of weeks ago, but available now, which is something of a sequel to this; also, go and read Martin Jay on the racket society. I’ll be back in a bit.

Read all you want; we’ll make more.

I’ll be puzzling over this one for a spell.

Meanwhile, I’d suggest you check a copy out from the library, but even though they added ten more copies to keep up with demand, there’s still a waitlist. So if I might humbly suggest the source itself?

A journal of the urn burial.

The text has been set in Tribute, says the colophon, a typeface designed by Frank Heine from types cut in the 16th century by Françoise Guyot; specifically, a specimen printed around 1565 in the Netherlands.

It does no good whatsoever to call it a coincidence, that in my dilatory reading/re-reading of Nevèrÿon, I’ve ended up in the Tale of Plagues and Carnivals right about, well, now, but I have, and it is, and, well.

7.5 Historically the official reaction to plague in Europe was the one described by Defoe in A Journal of the Plague Year (1722): “The government… appointed public prayers and days of fasting and humiliation, [and encouraged the more serious inhabitants] to make public confession of sin and implore the mercy of God to avert the dreadful judgment which hung over their heads… All the plays and interludes which, after the manner of the French Court, had been set up, and began to increase among us, were forbid to act; the gaming-tables, public dancing-rooms, and music- houses, which multiplied and began to debauch the manners of the people, were shut up and suppressed; and the jack-puddings, merry-andrews, puppet-shows, rope-dancers, and such like-doings, which had bewitched the people, shut up their shops, finding indeed no trade; for the minds of the people were agitated with other things, and a kind of sadness and horror at these things sat upon the countenance even of the common people. Death was before their eyes, and everybody began to think of their Grave, not of mirth and diversion.”

Defoe’s last few lines may betray that this is the official interpretation of the response as well as the official proscription: if there was, indeed, “no trade,” why would these merrymakings need to be “forbid,” “shut-up,” and “suppressed”? At any rate, even in Artaud’s conservative schema, once “official theater” is banished during the plague, the reemergence, here and there, of spontaneous theatrical gestures in the demoralized populace at large throughout the city represents, for him, the birth of true and valid art/theater/spectacle.

And there’s everybody trying to make some sort of point by carrying on as if business were usual, going out to the bars and the Red Robins and St. Patrick’s Day shenanigans because we’re Americans and we do what we want no matter what like the coronavirus is some kind of terrorist we refuse to appease, and there’s all those videos of Italian neighborhood serenades, and there’s this, too, from a prior time of plagues and carnivals, when the ratchet managed for once not to crank to the right—

—but there’s also all the photos of nightmarish airport lines, and now I’m thinking about another book with a plague, and a carnival, that wrote the writing of it into itself—

Last week a nightmare. Landed at Dulles and arrested in Immigration. On a list, accused of violating the Hayes-Green Act. Swiss gov’t must have told them I was coming, flight number and everything. What do you mean? I shouted at officious official. I’m an American citizen! I haven’t broken any laws! Such a release to be able to speak my mind in my native tongue—everything pent up from the past weeks spilled out in a rush, I was really furious and shouting at him, and it felt so good but it was a mistake as he took a dislike to me.

Against the law to advocate overthrowing US gov’t.

What do you mean! I’ve never done anything of the kind!

Membership in California Lawyers for the Environment, right? Worked for American Socialist Legal Action Group, right?

So what? We never advocated anything but change!

Smirk of scorn, hatred. He knew he had me.

Got a lawyer but before he arrived they put me through physical and took blood sample. Told to stay in county. Next day told I tested positive for HIV virus. I’m sure this is a lie, Swiss test Ausländer every four months and no problem there, but told to remain county till follow-up tests analyzed. Possessions being held. Quarantine possible if results stay positive.

My lawyer says law is currently being challenged. Meanwhile I’m in a motel near his place. Called Pam and she suggested sending Liddy on to folks in OC so can deal better with things here. Put Liddy on plane this morning, poor girl crying for Pam, me too. Now two days to wait for test results.

Got to work. Got to. At local library, on an old manual typewriter. The book mocks: how can you, little worm crushed in gears, possibly aspire to me? Got to continue nevertheless. In a way it’s all I have left.

The problem of an adequate history bothers me still. I mean not my personal troubles, but the depression, the wars, the AIDS plague. (Fear.) Every day everything a little worse. Twelve years past the millenium, maybe the apocalyptics were just a bit early in their predictions, too tied to numbers. Maybe it just takes a while for the world to end.

Sometimes I read what I’ve written sick with anger, for them it’s all so easy. Oh to really be that narrator, to sit back and write with cool ironic detachment about individual characters and their little lives because those lives really mattered! Utopia is when our lives matter. I see him writing on a hilltop in an Orange County covered with trees, at a table under an olive tree, looking over a garden plain and the distant Pacific shining with sunlight, or on Mars, why not, chronicling how his new world was born out of the healthy fertility of the old earth mother, while I’m stuck here in 2012 with my wife an ocean to the east and my daughter a continent to the west, “enjoined not to leave the county” (the sheriff) and none of our lives matter a damn.

Also, to design a font based on a Renaissance Antiqua had been a long held desire for Heine, who said “I am particularly attracted to its archaic feel, especially with settings in smaller design sizes. It is rougher with less filigree than the types of the following centuries thus exhibiting much cruder craftsmanship of the early printing processes.” By using a third generation copy as a model, which did not reveal much detail, allowed Heine enough room for individual decisions resulting in a decidedly contemporary interpretation while maintaining a link to the past.

When I haven’t been reading Delany, or Robinson, or Eddison, or McKillip, or Macharia, or Warner, or helping to prep our office for mandated telework, or reflexively reloading the Twitter feeds of friends, I’ve been setting the type for the revised paperbacks. It’s something I can do over there, on the big monitor: since the final (final) edits were done on the ebook files, I have to copy and paste the text a section at a time, tweaking the kerning as I go to fix the capricious judgment of the automated hyphenator, and to make sure the widows and orphans are cared for, and it’s peaceful, soothing work, handling the text in those Renaissance Antiqua shapes, re-reading this bit or that as I lay them out, remembering, re-thrilling, re-embarrassed, and I can look up and find an hour or three has passed, at four in the morning, at ten at night, but it’s, well, it’s, things get done, you know? There is a measurable sense of progress. Still. I look over to the other screen, in another window, where something-or-other has maybe been playing, A Knight’s Tale, say, or Hannibal, I mean, I really like his neckties, you know? But under it, behind it, always all around it, those tweets, that news, these people, driving us over a cliff because they will not let go of the wheel. —I have to go and walk to the office in a bit here (avoiding public transportation), making sure the skeleton crew has what it needs to keep up with the physical labor that still must be done (answering phones, scanning the paper mail, handling secure faxes, keeping the computer network up), but until then, I look away, look back, spread the letters of that line apart just enough so that Ysabel’s name isn’t split between Ys- and abel. Too much of that sort of thing catches the eye. Draws you out of the flow. Breaks the spell.

A scattered dynasty of solitary men has changed the face of the world. Their task continues. If our forecasts are not in error, a hundred years from now someone will discover the hundred volumes of the Second Encyclopedia of Tlön.

Then English and French and mere Spanish will disappear from the globe. The world will be Tlön. I pay no attention to all this and go on revising, in the still days at the Adrogue hotel, an uncertain Quevedian translation (which I do not intend to publish) of Browne’s Urn Burial.

This year, said Thucydides, by confession of all men, was of all other, for other diseases, most free and healthful.

Sufficient unto the day.

Closing the libraries is wildly grim. “The library branches’ WiFi signals will remain turned on for anyone who wants to sit outside a building or in the parking lots,” but, and yet, I mean, well. And still. —One might well note that ebooks are still available; one might well note that the 2019 Library Writers Project selections have just been announced; one might well—but still.

Folie à hirsute.

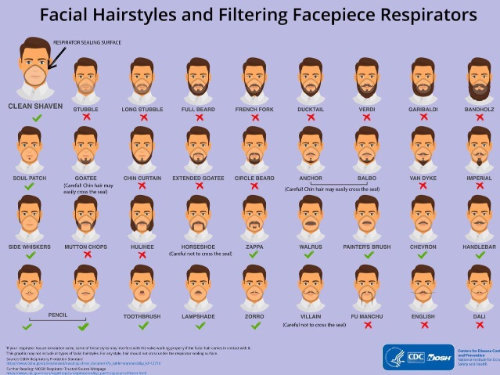

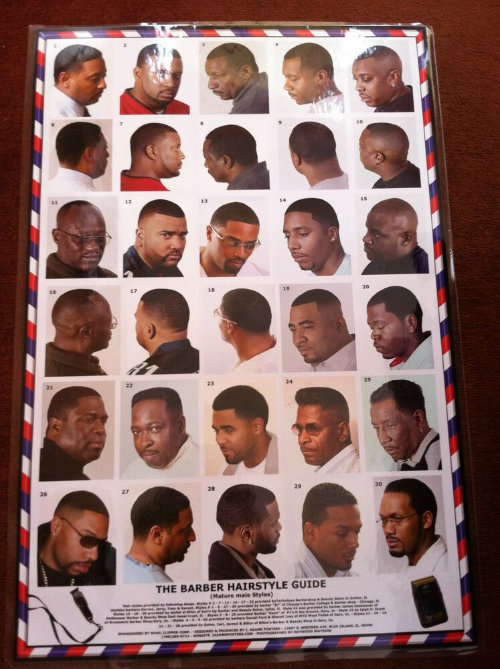

You have more likely than not seen this—

—which some have likened to this—

—or maybe you’re thinking of this—

—but me, I was suddenly, implacably flung back to this—

—so. Anyway. —I’m not sure where I fall on the charts—Fantasy Garibaldi, I suppose, but more effusive; anyway. I’m not choosing to think about what I’d have to do to properly fit a respirator. Yet.

In the reign of good Queen Dick.

Speaking of indulging me, I almost forgot to mention—

It’s new book day! Being the almost entirely arbitrary date selected for making the ebook of Vol. 3 of City of Roses available to the general public. (Almost entirely: I didn’t finish the Foreword ’til Monday, so.) —You can buy it from Smashwords, or any of the fine ebook purveyors Smashwords supplies, which maybe might include Amazon, I guess, oh, wait, no, the book has to have sold two thousand dollars’ worth through Smashwords, first. —Ah, I’m not bothering with the Borg so much anymore anyway; it’s not like this is about selling, ha ha, books, so. (If it were, I doubt I would’ve gone with “a wicked concoction of urban pastoral and incantatory fantastic” as my logline, which replaces “gonzo noirish prose,” and I expect you all to update your marketing kits accordingly.)

Or! You could buy them directly from me. I might not respond immediately, but certainly within an hour or three, and I get to keep more of the money, so it’s a win-win insofar as that goes.

Also! Available in Spanish, though not from me. (I think I mentioned these already.)

And there’s always the Patreon. (I don’t have a SoundCloud. That I know of.) —Anyway. Ha ha! New book day!

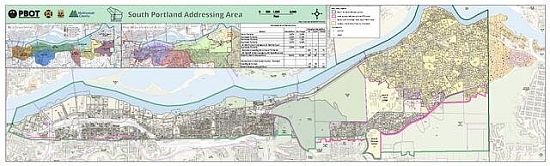

Cartographic spoiler.

If you’ll indulge me a moment:

“Portland,” says Ysabel, spreading marmalade on her toast, “is divided into four fifths.”

“Four,” says Jo. “Not five?”

“Four,” says Ysabel. Leaning over her plate she takes a bite of toast, careful of her sleeveless peach silk top. “There’s Northwest, Southwest, Southeast, and Northeast.” Her finger taps four vague quarters on the purple tabletop between her plate and Jo’s coffee cup.

“What about North?”

“What about it?”

“It’s a whole chunk of town,” says Jo, leaning back. The jukebox under the giant plaster crucifix on the back wall is singing about how you’re all grown up, and you don’t care anymore, and you hate all the people you used to adore. “Isn’t it one of the fifths?”

“There’s no one there.”

“There’s nobody in North Portland.”

“But few of any sort,” says Ysabel, shaking pepper on her omelet, “and none of name.”

“Okay,” says Jo. Stirring her coffee. “But it’s still there. It’s still a part of Portland. It’s still a fifth.”

“If you wish to be finicky, you might also note that there’s no one technically ‘in’ downtown, either,” says Ysabel, cutting a neat triangle from the corner of her omelet. “Or Old Town. So you might speak of six fifths. Or seven. But.” She forks it up, chews, swallows. “I’m trying to keep things simple.”

I always was inordinately happy with that wee early riff on Ireland’s four cóiceda (even if the Shakespeare’s a little on-the-nose). (They’re eating in the Roxy, by the way. I’m serious about being firmly set in Portland.) —So I was anyway initially dismayed to learn that the City of Roses is adding its first new cóiced since 1931:

I mean, “Portland is divided into five sextants” just doesn’t have the same swing, you know? And we’re going to lose the leading zero addresses in inner Southwest, which is one of those charmingly slapdash municipal solutions that seemed brilliant in the moment but now confuse the hell out of underpaid DoorDashers and Amazon delivery drones.

But it’s not like I’m rewriting the riff, and I’m not so concerned with rigorous historical accuracy—I mean, the grand struggle between Good and Evil hinges on whether or not to demolish a ramp that was torn down in 1999. (Oops. Evil wins. Sorry.) —And it’s certainly suggestive, this sudden new neighborhood, carving as it does the Pinabel’s waterfront condominiums and all that other economic development out of the heart of old Southwest. So something’s going to happen in the political situation of my fictional little kingdom—hence the spoiler warning above—only, I’m not yet sure just what that thing will be.

But I have some ideas.

It is easier to clean the kitchen if you keep the kitchen clean

is one of those astringently parsimonious bromides that isn’t worth the wisdom it reveals, but I can’t help but think it applies to the problem with bringing back blogs. I couldn’t begin to tell you why I’ve suddenly resumed a former, blistering pace, but I can say that hiatuses be damned, this blog, this long story; short pier, is now old enough to vote in most American elections. Go on, then; have a haggis—