Six hundred thousand words and counting.

A brief note on the appearance of the fortieth novelette, this week and next, over at the city; we’ve launched into Next Thing I Know, and are coming up fast (I hope) on Ain’t That Some Shit. —As the tagline runs: “In which forensics are seen to, and a beloved companion, a gift is given, and a window restored, portions are measured, and measures will be taken.”

I mean the matter that you read, my lord.

Matter matter matter, let’s see—we’ve moved, across town, from Ladd’s Addition to Rose City; we’re homeowners now, and again, which means we can paint the rooms the colors we’d like, but also means we have to strip and sand and sweep and repair and replace and prime and tape and paint and paint again, over and over for each different color, and, well. Time passes. You look up and wonder what you’ve accomplished and then you look around, and yes, but also yes, well...

As for words words words: as to written, and here you must imagine me sucking my teeth. I’ve got the fortieth novelette queued up and ready to go starting Monday, but that’s the only one I’ve written this year, and last year I managed to write most of five, and the discrepancy gnaws. I’d point to the work alluded to in the paragraph above, and the work associated with the day job (turns out, preparing for and supporting a federal criminal trial? Time-consuming), but work we will always have with us, and the work still needs to get done, and the forty-first isn’t at the moment coming any faster, and as for anything written around here, well...

But as to have read, have been reading, to be read: currently bouncing between two big books, each expansively large in their own particular idioms: on the one hand, I’ve decided instead of dipping in almost at random to sample this run of stanzas, or that, to work my way through the F--rie Queene from first line to last, drawing what dry amusement I might from the coincidence in age between myself when I finally started it (53) and Virginia Woolf, when she finally started it (53)—

The first essential is, of course, not to read The F--ry Queen. Put it off as long as possible. Grind out politics; absorb science; wallow in fiction; walk about London; observe the crowds; calculate the loss of life and limb; rub shoulders with the poor in markets; buy and sell; fix the mind firmly on the financial columns of the newspapers, weather; on the crops; on the fashions. At the mere mention of chivalry shiver and snigger; detest allegory; and then, when the whole being is red and brittle as sandstone in the sun, make a dash for The F--ry Queen and give yourself up to it.

—only to find myself at the end of the first 12 cantos looking up, blinking, as our avatar of Holinesse, that Redcrosse knight his own dam’ self, so happy in his ever-after with Una, his one true only, the only one true only, suddenly just ups and leaves her in the space of eight lines of iambic pentameter and a single alexandrine—and, I mean, I know why St. George leaves the personification of true religion to return to F--ry Lond, but I can’t for the life of me figure out how Spenser knew, or at least what Spenser knew, and wanted me as a reader to know, and it’s another of those weird bucks and hitches from out of time that keep kicking me loose from the poem and yet drawing me back all at once.

The other is Pynchon’s Against the Day, which if I were feeling glib I’d describe as Roszak’s Flicker meets Vollmann’s Bright and Risen Angels with a dash of let’s say Matewan; it’s like the reading and research I did back in the day for that never-to-be-realized mashup of Blavatsky and Lovecraft, Space: 1889 and the Difference Engine, all was homework for enjoying this—but such flippancy isn’t meet for any of the works in question. It’s baggy and shaggy and too much by half, I’m completely lost every time I slip back into it, but comfortably lost, reliably at sea, and the stew of language Pynchon and Spenser make when taken in alteration is heady indeed.

Heady, but thick, and slow-going, and see above re: work, and so these other books are piling up in the queue: John Ford’s last book, and Avram Davidson’s last Virgil Magus book, Mary Gentle’s Ash, the Moonday Letters and the Monkey’s Mask, the Underground Railroad and a half-dozen Queen’s Thieves, and that’s just the fiction, good Lord, there’s the White Mosque which isn’t even on my shelves yet, and Reading and Not Reading the F--rie Queene, which is, but, I mean, well...

As for what I have read, recently, well, I mean, there was Under the Pendulum Sun, which was fine insofar as it went, some lovely and divertingly weird imagery, but overall the book’s preoccupations weren’t my own, or rather weren’t what I would’ve expected them to be, given what we’re given, which resulted in some unfortunate undercooking here and gauchely overdoing it there and left me mostly with I’m afraid a shrug; and then there was Jawbone, which was spectacularly taut and exactly pretty much what I wanted it to be until it somehow utterly failed to end; and then there was, well.

Oh, it’s a big thick wodge of an epic, diligently working the post-Martin space, which is terribly au courant for epics, and it’s got a killer title, and that’s about all I can say for it—it has nothing like Ojeda’s power, or Ng’s charm, it sags tiresomely when it doesn’t race through suddenly ancillary quests for plot coupons (I’m afraid my disdain is such I’ll reach for overused critical terminology): an Anthropologie®-curated fantasy with a girlboss gloss that insists I see a dragon without doing the work to show me anything like a goddamn dragon. —But Shannon did make two moves, at least, that stuck with me, in how they kicked me loose, but without anything beyond my own cussedness to draw me back:

The first (which, as I’m piecing this together, I realize happens second in the book, but it’s the first I remember, so) is when great revels are thrown to celebrate the introduction of Sabran, our unmarried cod-Elizabeth I, to her proposed suitor Livelyn, our cod-Anjou:

The Feast of Early Autumn was an extravagant affair. Black wine flowed, thick and heavy and sweet, and Lievelyn was presented with a huge rum-soaked fruit cake—his childhood favorite—which had been re-created according to a famous Mentish recipe.

And at that I closed up the book, and looked about the bus (I was reading this almost entirely on the bus, in to work, and back home again), and then opened it up to the front to scour the maps—here, follow along—there’s the Queendom of Inys, or cod-England, and the Draconic Kingdom of Yscalin, or cod-Iberia, and the Free State of Mentendon, which I keep thinking of as cod-France, but is really more of a cod-Low Kingdoms (which makes doomed Lievelyn more of a cod–Holstein-Gottorp, I suppose); there’s cod-Lybia and a cod-Levant, and then over here on our other map we have wee cod-Nippon and but also the Empire of the Twelve Lakes, which is a cod-Middle Kingdom and not a cod-Minnesota—but what we don’t have is a cod-India, a cod-Cyprus, a cod-Madagascar, a cod-Madeira, a cod-Caribe, a cod-Hawai’i, not a cod-plantation to be seen—so when I read that a Prince’s favorite dessert is

a huge rum-soaked fruit cake

and you have countries and cultures and glimpses of history recognizably English and Spanish and Dutch and Japanese, and you tell me offhandedly you have rum, rum which if it is to be rum and not some phantastick honey liquor or something, but rum made from sugar, sugar from sugarcane (I mean, you can make rum from beet-sugar, but I’d hope you’d tell me it was beet-rum so I could take at least some visceral delight)—and sugarcane as such requires prodigious quantities of backbreaking labor to grow and harvest and process on a scale industrial enough to have enough left over to think to boil it into liquor, liquor enough that it might occur to a royal pâtissier, or banketbakker, to soak a fruitcake in a bottle’s worth to see what might come of it, you tell me that this is a thing in your world, but I look on your maps and I can’t anywhere find a trace of the God-damned Triangle—

—I’m gonna get flung right the fuck out.

The second move that stuck (which, again, now I’m looking at it, came first) is at once almost anticlimactically smaller and yet so very much more large: it’s a move made over and over throughout the book, but this was (for me, at least, at the time, for reasons) the most startlingly salient example, the one after which I could no longer ignore the bedevilment—it comes as Niclays Roos, disgraced alchemist and con artist, exiled before the novel begins from Mentendon to the lone Western trading post in Seiiki, our cod-Nippon, he’s being palanquined across the island to a mandatory meeting with the Warlord, and gets inexplicably dropped on his own in the middle of downtown Ginura, the Seiikinese capital, where he knows no one, nowhere, not hint of how to get to the Warlord, not a thing, until he coincidentally bumps into an old friend and colleague: Dr. Eizaru Moyaka, who, with his daughter, Purumé, had come some time before to Orisima, the aforementioned trading post, to study anatomy and medicine with this exiled Western doctor. Eizaru offers his modest house to Roos as a place to stay until the Warlord is ready, and Roos gratefully accepts; after all, he knows no one else here, nothing, no-how.

Eizaru lived in a modest house near the silk market, which backed onto one of the many canals that latticed Ginura. He had been widowed for a decade, but his daughter had stayed with him so that they could pursue their passion for medicine together. Rainflowers frothed over the exterior wall, and the garden was redolent of mugwort and purple-leaved mint and other herbs.

It was Purumé who opened the door to them. A bobtail cat snaked around her ankles.

“Niclays!” Purumé smiled before bowing. She favored the same eyeglasses as her father, but the sun had tanned her skin to a deeper brown than his, and her hair, held back with a strip of cloth, was still black at the roots. “Please, come in. What an unexpected pleasure.”

Niclays bowed in return. “Please forgive me for disturbing you, Purumé. This is unexpected for me, too.”

“We were your honored guests in Orisima. You are always welcome.” She took one look at his travel-soiled clothes and chuckled. “But you will need something else to wear.”

“I quite agree.”

When they were inside, Eizaru sent his two servants—

Wait—which the what, now?

We have a couple of academics living in a modest house—in the capital, on a canal, sure, nice little walled herb-garden, she’s answering the door herself, taking in an old friend on a whim, sure, but there’s a cat twining about her feet, and then, all of a sudden—servants?

This sudden, wrenching shift, the violent clash of assumptions, between what I’d expect of the class of a couple of modestly housed academics, worldly enough to travel to a distant, despised outpost for a chance to study with an exotically disreputable doyen, yet grounded enough to open their own door to visitors, and what the book was willing to prepare me to accept of their class, with the sudden irruption of these two servants, never named, never described, just there, to, to, I don’t know, to have done things, fetch water, keep the day’s heat at bay, lay out the food, deliver messages, to signal the class to which the doctors belong despite any other assumptions, to otherwise be ignored.

They’re of a piece, these similar ignorances: slipping a rum-soaked cake into a scene for the one set of connotations the word “rum” might bring, without taking into consideration all the others that freight the word; dropping a servant—two!—into a set-piece for no other reason and no other effect than that it is assumed servants of some sort must be there—a heedlessness severely detrimental to the building of a world.

But here’s me being awfully stern about an epic so—I’d say “slight,” I’d say “inconsequential,” but there’s stern again, and uncharitable. I mean, I did finish the dam’ thing, didn’t I? —And there, up above, did you catch it? When Virginia Woolf was telling us what we ought to do, and ought not do, before we set out to read the F--rie Queene? That we should “walk about London; observe the crowds; calculate the loss of life and limb; rub shoulders with the poor in markets—”

And who does it turn out to be are we, then, being addressed? And who, is it assumed, are not?

INT. HEADSPACE. DAY.

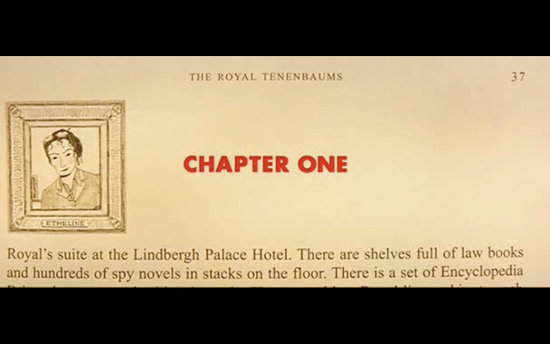

You know what’s really irksome about the Royal Tenenbaums?

It’s such an overtly, ostentatiously bookish film, from the inspiration for the grown-up whiz kids past their prime (everyone else will tell you it’s that Glass brood, but I’ll tell you it’s much more the ilk of Claudia and Jamie Kincaid and Turtle Wexler) to the obvious surface gloss of those exquisitely designed dust jackets, from the genially gravelly Narrator to the way it’s broken into chapters, with those primly typeset insertions—

—and there, that’s it, that’s what’s annoying: the text of the book we’re ostensibly reading as the movie unspools. If you read it (and it’s large enough to easily read, we’re given enough time), well. Ostensibility crumbles. —Oh, the first one, the Prologue’s okay: it’s just the Narrator’s opening lines, set down on the page and perfectly prosaic, excellently novelistic: “Royal Tenenbaum bought the house on Archer Avenue in the winter of his thirty-fifth year.” But the rest?

Chapter One as we can see starts off with “Royal’s suite at the Lindbergh Palace Hotel. There are shelves full of law books and hundreds of spy novels in stacks on the floor.” Chapter Four? “The side entrance of the hotel. Royal goes in through the revolving doors.” Chapter Seven? “The next morning. Richie comes downstairs. He carries the stuffed and mounted boar’s head.” The Epilogue? “A gentle rain falls in the cemetery, and the sky is getting dark.” —This isn’t the sort of prose to be found in books with those dust jackets, in novels written by Ellen Raskin or E.L. Konigsberg—these are passages from the screenplay of the movie that we’re watching, bald instructions to the production team, this is what needs to be seen to make the story happen, copied as-is and pasted just so, to lorem ipsum up a handful of grace notes in the movie’s art direction. Once you see it, you can’t unsee it, sticking out among all the other details so much more carefully considered. It irks.

I get a little twitchy, whenever the subject of cinematic writing comes up. —Cinematic writing, filmic writing, the screen-like æsthetic: here, let me grab a passage from Simon McNeil’s Notes on Squeecore, since that’s where I’m going to tell you it most recently came up:

Wendig is, perhaps, the clearest example of a novelist who writes in a filmic style. Now I think it’s important to draw out how I talked previously a bit about how this was a characteristic of Hopepunk—the mediation of a literary canon via its filmic representation being something I called out within the Hopepunk manifestos—but this isn’t so much a matter of Wendig mediating literature via its depiction on screens as it is Wendig drawing the screen structure back into the book. The crafting of an image becomes the chief concern of the novel in Wendig’s hands. Action is in the moment and the dialog is kinetic precisely because Wendig is trying to show his audience a moving picture rather than tell them a story. In a way the lionization of show, don’t tell, almost inevitably leads to the logic of a filmic literature. After all, internality often involves telling the audience how somebody feels. As “Show, Don’t Tell” becomes a hard rule, it’s not hard to see how an audience of would-be authors with an insufficient grounding in literature but a lot of exposure to television will inevitably interpret that to turn the page into a kind of screen.

Breezy, surfactant, imagistic, often in the immediately present tense and almost always the disaffectedly third person (first person in screen-like tips from teevee to vidya: first-person shooters, don’t you know): at its most amateurishly egregious, the iron law of SHOW DON’T TELL eats itself, as the prose insists on telling you the show that needs to happen in your head: bald instructions to the production team, as it were; passages cut and pasted from a screenplay. (Rather than show you a dinosaur, I tell you to see a dinosaur, to tie this to other ongoing threads.) —It can be intended as complimentary, to say of someone’s prose that it is cinematic, but there’s always a bit of English on the ball: oh, look, the writer’s trying so hard, the poor dear, to make prose do what it manifestly can’t—and anyway, everybody knows the book is always better than the movie. (Think of what it means, after all, what’s intended, when a television show is said to be novelistic.)

And, well, I mean, here’s me, then, and the epic: specifically imagistic, immediately present, disaffectedly third, cinematic, yes, okay, sure, filmic, all right, I’ll even cop to a screen-æsthetic, but only if I get to play with all the various meanings packed into “screen,” but but but I know what it is I’m doing, it’s not amateurish, honest, I’m sufficiently grounded and aware of if not all then at least a great many literary traditions—

See? Twitchy. And that’s never a good look on anyone.

I didn’t set down specific rules I’d follow, or at least not break, when I set out to figure out what I was going to do and be doing. It’s more that the rules assembled themselves, from what I wanted to pull off: an epically longform, episodic serial, and the best and most prevalent examples thereof at the time were superhero comics and hour-long dramedic television serials. So I leaned into that. —I’ve written before, about the differences between words, and moving pictures:

The primary difference between prose and cinema (beyond the obvious) is I think in time, and how each handles it; cinema (like theatre before it) no matter how achingly it might strive for universal generalities, must necessarily show you specific people doing specific things in specific places at very specific times. Prose, on its wily other hand, can say: “Monday morning staff meetings were always a chore for Willy” or “For the next week whenever she went to the coffee shop she saw the woman on the corner” or “And then everybody died.” —The narrow bandwidth of prose can’t begin to approach the wealth of incidental detail that makes up cinematic specificity without enormous slogging effort; most of the tricks and tips one needs to learn to tell stories and have them told with mere words, in fact, those reading protocols we’ve all had put in place, have everything to do with tricking us into thinking that specificity’s been achieved without us noticing (just as a great many of cinema’s tricks are all about forcing us to empathize with the saps up on the screen, bridging the vast gulf between their specificities and ours).

Setting out to ape the effects of one with the tools of another, though, is less about what I’m going to do (write with immediacy and specificity, as if, yes, I’m telling you what you’d see and hear if the story were playing out on a screen, yes yes) than what I won’t: generalize, pull back, sweep up and away from that immediate moment, that specific place. —And there’s one more thing prose does, that the epic does eschew:

Every narrative has a narrator. This may seem a ravelled tautology, but tug the thread of it and so much comes undone: a narrator, after all, is just another character, and subject to the same considerations. What might we consider, then, of a character who strives with every interaction for a coolly detached objectivity that’s betrayed by every too-deft turn of phrase? Who lays claim to an impossible omniscience, no matter how it might be limited, that’s belied by every Homeric nod? Who mimicks the vocal tics and stylings, the very accents of the people in their purview—whether or not they’re put in italics—merely to demonstrate how well it seems they think they know their stuff?

It’s only those texts that admit, upfront, the limitations and the unreliability of their narrators, that are honest in their dishonesty. —The third person, much like the third man, snatches power with an ugliness made innocuous, even charming, by centuries of reading protocols: deep grooves worn by habits of mind that make it all too lazily easy for an unscrupulous, an unethical, an unthinking author to wheedle their readers into a slapdash crime of empathy: crowding out all the possible might’ve beens that could’ve been in someone else’s head with whatever it is they decide to insist must have been.

I’d never presume to tell you what someone else is thinking, good Lord, no. That would be rude. Instead, I’m going to show you what it is they do, and say, and let you draw your own conclusions, and trust you to adjust them as we go.

Framing it this way, as what I’m not going to do, makes me mindful of the tools I’ve set aside, and turns those vasty fields untrampled into negative space—a very potent consideration in any composition: instead of showing you a dinosaur, or telling you to quick, think of a dinosaur, the hope is that these dotted moments, and the space implied between them, might at this moment or the next shiveringly resolve in your head into the suggestion, of a dragon-like, dinosaur-sylph—and all the more impactful, as it’s one you’ve made yourself.

A long way round, perhaps, but fitting, I think, for an idiom that seeks to immerse you in a slightly disjointed reality, to make you believe that at any moment a short sharp shock of the numinous might intrude. —At any rate: I’m having fun. The occasional twitch aside.

Actually, you know, the one for the epilogue’s okay, too? “A gentle rain falls in the cemetery, and the sky is getting dark.” That’s a fine-enough turn of phrase for a novel, or even a screenplay. Except of course for the fact that it’s not getting dark in the scene that then unfolds: the sky’s a fixed and dreary mid-afternoon. —The perils of adaptation, one supposes.

Fine china.

Oh, hey, twenty years. Happy anniversary. —I’m not sure if Gordon Sinclair kept flinging haggises—hagi?—across the Bow River; cursory internet searches suggest his patented flinger wasn’t so much a success—but then, we’re none of us doing too well. If you’d come to me, then, to tell me that twenty years on we’d be entering the third year of a global pandemic, determined to forget any lessons we might accidentally have learned; that the Objectivists who’d taken over Silicon Valley would be cheerfully conspiring to break every utopian promise the internet had ever made for the sake of an energy-guzzling money-laundering bookkeeping trick; that we’d be staring down the barrel of an inevitably impending Christofascist takeover, and the only thing the Democrats could think of to fight it was to lionize Dick “Torture” Cheney, I mean, honestly: in the list of what-the-fuckeries piled up over the past twenty years, the fact that Donald freaking Trump is an odds-on favorite to win a second term as president barely cracks the top five.

Then again, I always was a pessimistic curmudgeon.

If you’d like to look back, to when blogging was a thing, and we weren’t yet rocketing up the hockey stick, there’s the previous retrospectives: the ten-year argosy (posted 3,635 days ago) and the 2019 update; to which from the past couple of years I’d add maybe this one, and this one, and let’s not read too much into the fact they’re both needling George R.R. Martin?

So, yes, it’s been quiet hereabouts. I did write five novelettes last year, which might help to explain some of it, maybe? —The epic’s up to 586,000 words, which is 34% of a Song of Ice and Fire, and I said we weren’t going to read too much into this.

Anyway. See you when I see you.

A clay envelope or hollow ball, typically with seal impressions or writing on its outside indicating its contents.

Someone, somewhere, recently pointed out that you don’t see the sainted Limbaugh’s favorite insult, “feminazi,” being tossed about with quite such abandon anymore, now that the right’s decided maybe the Nazis had a point.

That’s the sort of observation that’ll stick in your craw, if you let it.

I’m caramelizing (well, roasting) cabbage tonight, and if I were still on Twitter, I’d needle Keguro about it. Or roast him. I mean. You know what I mean.

This is mostly what has occupied my mind, mostly, of late: high-minded despair; quotidian satisfaction. On the one hand, there’s strong evidence a not insignificant number of Supreme Court justices want to do away with Gideon, and thus the very basis of my job; on the other, this new technique of cooking the noodles with the milk has kicked my macaroni and cheese to the next fucking level, let me tell you. —The whipsaw, ever and always.

I mean, anyway. That’s how I am. How are you?

The cabbage was delicious, by the way.

So forgive me, I guess, is the basic point, if I go on about what I’ve been doing over there, but it’s what I’ve been doing: the entire Trump administration, I managed to write six installments; in this, so far, the first year of the Biden interregnum, I’ve (just about) written five alone. That, such as it is, isn’t nothing. —And so.

Anyway. That’s how I’ve been. How you doin’?

The fingers in your glove.

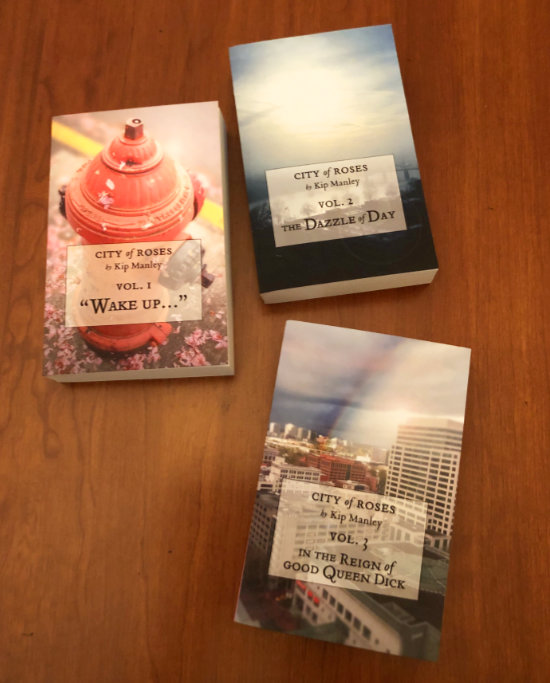

Yeah, I know, but I’ve been busy over yonder, epic-wise. Look! New chapbook day! Again!

Sounding brass; tinkling cymbal.

Oh, dear. —Bryant Durrell, friend of the pier, went and remembered something I wrote (checks dates) seventeen years ago, and while it’s not that I wish that he hadn’t (one is pleased, after all, to be remembered), still: his assessment of me-then as “overly charitable” is, itself quite graciously charitable; me-now, looking back over that intractably defensive meander, would rather call me-then “gormlessly naïve.” —But time has passed, great seething gobs of the stuff, and the only benefit one can scrabble from its passing is whatever might pass for wisdom: I’d like to think I’ve become a wee bit better at reading things, and reading how they might be read; much less sanguine, anyway, about an author’s ability to keep such material from turning in their hands and pointing the way it’s always going to point without inhuman effort, whatever intentions might charitably be imparted to them in the use of it. —There’s so much more and other more desperately needed work to be done, before we can set ourselves to play in fields like that.

We interrupt this narrowcast.

So the first chapbook of the fourth volume premièred on the web back in December; the second chapbook will make its debut one week from today, on February 8th, and appear in Monday-Wednesday-Friday installments for the next two weeks. So, hey: words are getting written. —In the meanwhile: if you do enjoy the work being done by the epic, or the notion of the work the epic would like to be doing, might I ask you to consider, for a moment, at least, supporting it with your patronage? Depending on the level at which you subscribe, you might already have gotten to see the story-time calendar I’m using to keep my discourse-time untangled; you might already have (in EPUB, MOBI, or PDF form) a copy of that next chapter, weeks before the (wonderful, lovely, couldn’t get by without ’em) peanut gallery has a chance to read it; your name might well be on an envelope I’m addressing tomorrow, to ship you a paper copy. Do consider it? —And, that consideration having now been taken, we return you to your regularly scheduled scroll.

Hey, nineteen.

So the pier’s been around for a while. (Apparently, bronze is the appropriate metal for any gifts on such an occasion.)

Begin as you mean to go on.

Stagger toward consciousness under the insistent paws of the older cats, wondering where breakfast is. Sit up, fish last night’s sweater from the floor, slip into it. Quietly to the bathroom to void the bladder and wonder, vaguely, if the toilet’s recently sluggish drain is merely due to an uptick in toilet paper usage, that might be remedied by a faintly stern lecture at some point, or something deeper, older, more severe, that will at some point require professional help. Into the kitchen, followed by the aforementioned cats, but quietly, quietly; it may be an hour later than usual, but it’s still some hours before everyone else. Switch on the kettle, crack open a can, a spoonful each in the bowls of the older cats. Grind the coffee. Rinse out the French press. As the water works its way to a boil, stick a head in the daughter’s room to check on the kitten, who’s sat, alert but sleepy, on her sleeping shoulder. Tip out the ground coffee. Stir in the water just off its boil. Mix up the poolish for the pompe a l’huile, and notice for the first time that the recipe just says “salt,” and not how much. Figure it’s a teaspoon, given everything else, but that’s for later, after the poolish has had time to ferment. Plunge the coffee, pour it into the thermos, pour out a cup. Sit down. Light the candle. Draw the card. Fire up the keyboard and turn to the first draft of the first scene of the thirty-fifth novelette. Figure maybe it’s time to commit to the occasional use of a question mark as an aterminal mark of punctuation, indicating a rising tone in the middle of a sentence, but not the end of it—but only in dialogue, and only when separated from the rest of its statement by some sort of dialogue tag? he said, uncertainly, but sure, okay, let’s do it. And what about whether or not he straight-up asks her where she’s going: say that out loud? Let it be inferred? Decide. Decide. There’s three more scenes to edit today to hit the pace we’d like. Let’s go.

20/20 hindsight.

What did I do this year, the year we decided to do the same thing we do every year, which is to bring blogging back. —Besides get translated and publish a book and begin the process of de-Amazonification and put out a ’zine and write another novelette, none of which is blogging, per se. Let’s see: I rather like this one, which only looked like it was sort of mostly about Watchmen, and this one, which is really mostly David Graeber, only then he had to go and die. This one, about book design and Entzauberung, is the sort of post I’d like to think I miss most about blogging; this one, about comics and formalism and serials, I’d like to think could’ve been, if maybe I’d worked it over one more time; this is the sort of genial shit-talking I always think these days I never have the time for anymore, even though they don’t take long at all; and this is the sort of thing commonplace books were intended for, I’d like to think. And I’m most awfully fond of this one (another entry in the Great Work) and most especially this one (yes), if not so much the third in the sequence, which wasn’t ever really supposed to be a sequence, but I’m sure you’re noticing all of these are from, like, the very beginning of the year? Before the Occupation of Portland by the zelyonye chelovechki, before the election and its ghastly aftermath sped up the grindingly long-term fascist coup enough for everybody else to see it, before the pandemic really settled in and took hold, and the bleakly short-sighted stupidity, and, well, I mean, 2020, y’know? I mean, it’s not like I gave it up entirely, I was still posting stuff I’d include in a year-end round-up, but I did skip the entire month of October, so. —I do have a Big Stupid Idea that I might start chipping away at. And I’ll try to make a point of not dismissing little stuff before I can post it; sometimes big things come from little stuff. —And I mean, 2009 was a pretty good year for blogging, wasn’t it? (Oh, hey, I was poking at Watchmen then, too!)

Fully automated hauntology.

I do wonder how authors dealt with the memories of cities and the ever-changing fabric of their ever-present selves in the days before we had Google’s Street View, and specifically now the history slider, letting you slip back and back to see what it looked like the last time one of those camera-mounted cars wandered these same streets, or the time before that: oh, look! you say, cruising past your own house on the monitor of the computer within it. Our car was parked right out front that day. What a curious sense of pride. (—If I were in my office instead, I might look up to see the enormous map of Ghana on the wall, and decide to walk the streets of Accra for just a few minutes to clear my head; we can do that, sort of, now.) —But there are costs, and slippages: this morning I was trying to find an appropriate bus stop to loiter at, needing to catch the no. 6 bus up MLK to (eventually) Vanport; I was reminded they’re building a building there now, where once had only been a parking lot, and a Dutch Bros. coffee cart, and happened upon a view of the construction site from April of 2019, when the first floor had been set in concrete and rebar, waiting for six more wood-framed storeys to balloon above it, but I stepped sideways, into another stream of views, that only offered September or June 2019 (the wood having bloomed now clad in brick, or what passes for brick these days) or August 2017 (the lot, the coffee, the light already different, as if lenses have changed enough since then to be noticed), and so here I am, with a morning spent bootlessly wandering over and over the same corner and streetfront, trying to find the precise spot from which I can once more catch that bygone glimpse of April, of last year.

Half a million words.

So the thing-that-argues (the argument itself being scattered in pieces all over the pier)—and, I mean, wait a minute. Maybe—maybe it’s about time, when you’ve amassed a corpus like this—

—maybe it’s time to stop being quite so self-indulgently coy?

So the epic (I think we can call it an epic, now, right?) just passed a milestone: with the release of no. 34, the first chapbook of vol. 4, —or Betty Martin (and here’s one of the problems of the epic: the cruft needed to identify exactly where you are in the flow of the thing)—anyway, the epic just passed the half-million word mark. These three book-shaped objects—

—plus this slender, unassuming ’zine (appearing in installments Monday-Wednesday-Friday for the next two weeks)—

—add up to 511,358 words, according to this device on my desk here (minus the furniture of introductions and forewords, of course): why, that’s just over 29% of a Song of Ice and Fire!

—Anyway. Forgive me my indulgences, as I forgive those who indulge me; I just figured the occasion ought to be marked, somehow. I’ve been at this a while. There’s a whiles yet to go.

Two-score and a dozen years ago.

Monday’s child is fair of face, they say, so hey—I got that going for me.

The visible world is merely their skin.

Altogether elsewhere, an interlocutor described the work of someone whom I haven’t read, for reasons, as, and I quote, “filmic and competent and all surface. And all the epigraphs only makes things worse,” and I know, I know, it has nothing to do with me, per se, but still: I felt so seen. —I do wonder, sometimes, as to how and why and the extent to which I’ve decided that the thing-I-do-with-prose should be so devoted to things prose is not supposed to do, but it’s like they say: anything worth doing is worth doing backwards, and in heels. [Strides off, whistling “Moments in the Woods.”]

Manichæan.

I might’ve made a mistake when I began the thing-that-argues. —Because I could not hear myself constantly and on a regular basis referring to Jo as a white woman (or, God forbid, a White woman), it would not be fair to single out Christian, say, by referring to him as a Black kid, or to Gordon as a black man.

Because I would not mark all of them, I could not mark any of them, so as to mark them all the same. The logic’s ineluctable.

But, you know. Logic.

It’s not just a matter of black, or Black, and white, of course. —How would you go about marking Ellen Oh? Would you say she is Korean? Even though she was born in Alabama, and most of her family hasn’t lived in Korea for a couple generations now? (Can you specify to any useful degree the differences in appearance between all possible individuals whose forebears might at one point have been sustained by that mighty peninsula, and the appearances of anyone, everyone else, that would render such a marker immediately perceptible, and adequately useful?) —You might perhaps think “Asian” to be an acceptable compromise, as a marker, but look for God’s sake at a map: Asia’s everything east of the Bosporous. How staggeringly varied, the appearances of everyone from there, to there! Worse than no mark at all, distorting marker and marked, and to no good or necessary purpose.

(The Ronin Benkei was flatly Japanese, even though Farrell was much too polite ever to notice more than a few echoes of classical Japanese manners in the gestures of Julie Tanikawa, whom he never heard swear in Japanese, except that once, for all that she spoke it as a child, with her long-dead grandmother.) (And as for Brian Li Sung—oh, but comics have their own markers, at once far more persnicketily precise, and yet so roomily ambiguous, and I’ve said too much.)

It’s not that the characters aren’t marked at all, of course: just not with such totalizing, reductive, contingent signs. Everyone’s described in much the same manner: their clothing, the way they carry themselves, their hair, how they say the things they say, the way the light hits them (the visible world being merely their skin)—the hope, of course, being that these pointilist details will accrete into a portait in the reader’s mind—inaccurate, perhaps, at the start, but resolving over time toward something more and more like what’s intended. (—Or, to be precise, what’s needed to make what’s intended work; this is imprecise stuff, this work, but really, think about it: how could even a single person, that is so large, ever fit within a book that is so small?)

But what does such a cowardly refusal on the part of the narrative voice, to plainly mark what any other medium would’ve plainly marked, by virtue of not being limited to one word set after another—what does this do to a reader’s relationship with the portrait they’ve been assembling when it suddenly must drastically be rearranged, after thousands upon thousands of those words? (I mean this at least is gonna hit a bit different than Juan Rico offhandedly clocking himself in a mirror on page two hundred and fifty.)

But let’s turn it around a minute: is it my fault if you didn’t assume from the get-go that an un(obviously)-marked character in a novel written by a white man, in a rather terribly white idiom, set in one of the whitest cities in the country—is it on me if you’re the one who assumes, before you’ve been told, that this character’s clearly white?

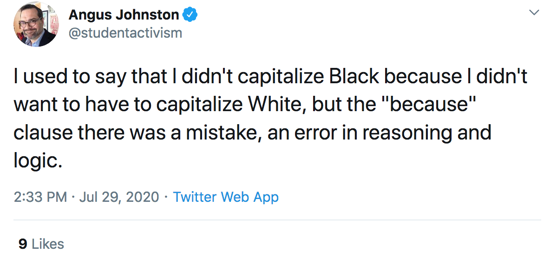

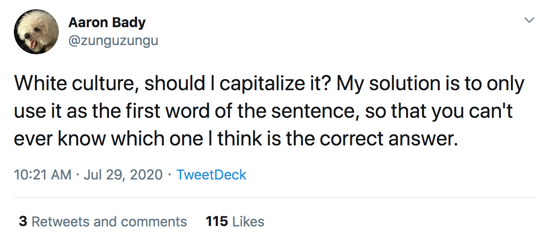

My own take on the question of the moment, or at least of the moment when I began sketching this out (though I’ve been thinking about something like it for a while now; it might’ve been the foreword of the third book, had anything coalesced in time)—my own take is not unlike what’s laid out by Angus above: because I would not dignify the constellation of revanchist grievances, the cop’s swagger and the supervisor’s sneer, that make up the bulk of what passes for the race I could call my own—because I would never capitalize that—well. Logic demands. Right?

But it’s ad fastidium, is what it is. —I could bolster it with an argumentum ad verecundiam, by turning to what Delany’s said, on his own perspective on the subject, bolstered in turn by Dr. DuBois’:

—the small “b” on “black” is a very significant letter, an attempt to ironize and de-transcendentalize the whole concept of race, to render it provisional and contingent, a significance that many young people today, white and black, who lackadaisically capitalize it, have lost track of—

Oh, but that was written in 1998, which is further away than it seems. Which is not to say anything’s changed, good Lord, I wouldn’t know, I only ever had breakfast the one time with the man, and we mostly talked about Fowles. But then, there’s this, from 2007, or 2016, depending:

“And those aren’t races. Those are adjectives of place—like Hispanic. And Chinese. Caucasians are people from the area in and around the Caucasus Mountains, which is where, at one time—erroneously—white people were assumed to have originated.”

“Latino..?”

“And that refers to the language spoken. So it gets a capital, like English and French. There is no country—or language—called black or white. Or yellow.”

But when he told this to a much younger, tenure-track colleague, the woman looked uncomfortable and said, “Well, more and more people are capitalizing ‘Black,’ these days.”

“But doesn’t it strike you as illiterate?” Arnold asked.

In her gray-green blouse, the young white woman shrugged as the elevator came—and three days later left an article by bell hooks in Arnold’s mailbox—which used “Black” throughout. He liked the article, but the uppercase “B” set Arnold’s teeth on edge.

And yes, it’s much the same argument! But it sits very differently, with different emphases and outcomes, when it comes from the mouth of Arnold Hawley, such a very fragile man—not Delany’s opposite, no: but still: his reflection, seen in a glass, darkly, as it were.

(Everyone knows there is no country called black, or language. What capitalizing the B presupposes is: maybe there is?)

But my own take on whether to capitalize “black” has no bearing on the thing-that-argues—in part because I’ve short-circuited it entirely, yes, but also and mostly because none of the people in it give a damn what I think, nor should they: the thing-that-argues, when it turns its attention to any such matter, should only ever care what it is they think, and how, and why: Christian thinks of himself as a Black man, for all that Gordon sees him as a black boy; H.D. sees herself as a Black businesswoman, concerned as she is with Black businesses; Udom, the new Dagger, still thinks of himself as from Across-the-River, though he knows most everyone these days sees him as one of the Igbo; Zeina, the new Mooncalfe, would probably say she’s black, or crack a bleak joke about Atlantis, and drowned mothers-to-be, or maybe she’d punch you, I don’t know; and Frances Upchurch (though that is not her name) would tell you exactly what you’d think she would, and never you’d know otherwise. —And each of them must be able to believe what they believe, to fight for it, or change their minds, without ever having to worry about some quasi-objective narrative voice thinks maybe it knows better blundering up to flatly gainsay them, this white voice in a terribly white idiom telling each and every reader that this was said by a Black man, or that was thought by a black woman, tricking these readers, every one, into thinking they maybe know what the author thinks—or worse, what the thing-that-argues thinks—and thus, what ought to be right, and further thus, who should be, could be, must be wrong. —And this understanding extends to all things.

(The narrative voice of Dark Reflections does not capitalize “black,” when referring to jeans, or to people, and so we can think we know what the author thought just a few years ago, or at least his copyeditor.)

So maybe I made a mistake at the start of it all. But there was thought behind it? At the start? Reasons to have done it, not that those are a guarantee of any God damn thing. —Maybe I’d do it differently, I were setting out today. Maybe I still regret using quotations marks, or writing it down as “Mr.” instead of “Mister.” But here we are.

There is a strength in writing as a fool, you do it right. Talking outside the glass. The room, that negative space affords, for the characters, for the story, for the readers (or so I tell myself, but I am a fool)—there’s power, in setting a taboo like this. You may not talk inside the glass, but still: you spill enough words, the shape of the glass can start to be made out.

Move fast; break things.

One is not unaware of a certain disgruntlement in certain quarters regarding a certain operation to which one has recently bound oneself; one looks at the one hand, one looks at the other, one manages a shrug of a bromide, life is compromise, I don’t know. It’s another of those situations where the structure is such that your choice or my choice can’t make a dent in the structure, but it’s all the structure will afford any one of us. They’re burning the postal service to the ground to steal an election—you maybe wanna buy a book? Could help pass the time until a general strike’s declared.