The war that will end war.

We’re a fifth of the way into the 21st century, and Chris Teso, founder of Chirpify.com and guest-columnist for Oregonlive.com, wants us to end our war on cars. —I used to have to commute in a car, and am thankfully blessedly once more in the position of NOT HAVING TO, of being able to catch one of the regular busses that stops just about right outside my house, or even when the mood takes me walking leisurely over the river and into downtown to get to work, and this is a luxury, I know, but one I’d share with everyone I could, and I stare perplexed at those who think they’d willingly turn it down for a chance to sit ensnarled in choking traffic: who does that? (People who seem to think having to sit next to a stranger on a bus is somehow an invasion of privacy, but we digress.) —I’m glad folks elsewhere took note of this entitled little screed, and took issue with its faulty logic and framed statistics, because damn: we’d do so much better to actually fight a war on cars, instead of all our wars for cars—I mean, can you believe this old bumper sticker is still searingly fucking relevant?

Rise of Something-or-other.

I don’t read novels. I prefer good literary criticism. That way you get both the novelists’ ideas as well as the critics’ thinking. With fiction I can never forget that none of it really happened, that it’s all just made up by the author.

So in other news of the-criticism-of-things-I-have-no-intention-of-seeing-myself, the Laverys went to see the new Star Wars and then had a conversation about it, and why would I subject myself to almost three hours of G-mergate capitulation when instead I could enjoy a frothy interplay of ideas that careens from Grace, taking up the question Lili Loofbourow asked, back when the first (the seventh) first came out—

The thing that has stunned me about Star Wars, for decades, has been the franchise’s extreme casualness about mass death. In The Rise of Skywalker, someone destroys a planet as a kind of flirtatious joke—“This’ll light a fire under their asses!”—and the effects of that catastrophe disappear from the screen within a couple of seconds.

—to Daniel’s reaction to (the lack of) the queering of (the lack of) Finn and Poe—

All I can think of with that “two men refusing to kiss? That’s a story” is the old “headless body found in topless bar” bit about what makes for really good headlines. I picture Sedgwick in full JJ Jameson drag, complete with cigar, yelling over the phone: “Two men refusing to kiss? Get me the photographs!”

—so anyway. Go; read.

Sed quis non custodiet ipsos custodes?

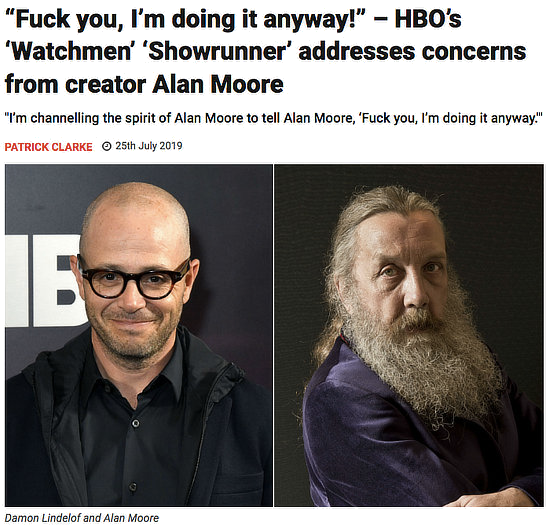

If I have to hear one more goddamn television producer insist their multimillion-dollar teevee show is really, truly punk—

—I swear to fucking God—

I’m afraid that for a few years now, I have felt that since I am apparently not allowed to own the work that I created in the same manner that an author in a more grown-up and worthwhile field might expect to do, and since my protests at having my work stolen from me are interpreted by a surely young-at-heart and non-unionised audience as evidence of my “grouchiness” and “cantankerousness,” then the only active position that is left to me is to disown the works in question. I no longer own copies of these books and, other than the earnest creative work that I put into them at the time, my only associations with these works are broken friendships, perfectly ordinary corporate betrayals and wasted effort. Given that I will certainly never be reading any of these works again and that I have no wish to see them or even to think of them, it follows that I don’t wish to discuss them, sign copies of them or, indeed, have anything to do with them. As I would hope should be obvious, to separate emotionally from work that you were previously very proud of is quite a painful experience and is not undertaken lightly. However, having to answer questions about my opinions regarding DC Comics’ latest imbecilic use of my characters or stories would be much more harrowing. And, of course, it’s not as if I don’t have plenty of current work to be getting on with.

—so yeah, I was not shall we say well-disposed to the idea of a televisual sequel to Watchmen. Sure, by all accounts it was gonna be better than the last attempt to frack monetary value from the IP’s shale (but Christ, Zack Snyder is such a low bar), and I will admit my resolve (if such a curmudgeonly disdain might be dignified with such a word) weakened when I heard what they’d managed to pull off with Hooded Justice, but then I heard what they did with Laurie and Dr. Manhattan and Ozymandias and Angela Abar and Lady Trieu, and my resolve redoubled.

Should we be surprised that Damon Lindelof’s Watchmen made Lady Trieu the bad guy? That a character named after Bà Triệu, a legendary third-century nationalist hero who resisted the Chinese occupation of Vietnam, must in the end be stopped by the combined efforts of two white men associated with the genocidal destruction of multiple civilian populations (the Manhattan Project, the bombing of Vietnam itself, and the squid-fall of New York)? Should we be surprised that a show which began with an airplane dropping bombs on Tulsa provides narrative closure by thwarting Trieu’s evil plans with “a gatling gun from the heavens” fired at Tulsa? (The gatling gun, briefly used in the American civil war, and extensively used in colonial subjugation.) How did Lady Trieu, would-be avenger of colonial-violence-from-the-heavens, become the victim of yet another righteous iteration of death from the skies?

That’s from Aaron Bady’s wrap-up at the LARB, which is exactly what you’d expect from him on something like this with a title like that. —Just because I’m not gonna bother watching the show doesn’t mean I’m not going to read what people have to say about it, much as I’ve been staring agog at every Skywalker spoiler that seeps within my purview (they fucking did what now with his futhermucking X-wing?). —The one that’s stuck with me the most, most recently, has been Jaime Omar Yassin’s “Black, White, Blue”—

Lee characterizes the print Watchmen as a brilliant, subversive anti-racist and anti-fascist text that Lindelof’s TV show fails to live up to. I loved Moore’s Watchmen and have re-read it half a dozen times over the years, and that’s why I’m confident that the original text is a really unfortunate platform to launch these critiques from.

Moore built an ugly super-hero landscape, mired in imperialist politics, narcissism, cultural chauvinism and white supremacist zeitgeists, true. The birthplace of superheroing is the “Minutemen” a WW2 era group of morally-confused and easily-corrupted narcissists working under a white supremacist, capitalist definition of right and wrong who donned capes for uninspiring reasons. Moore’s work has always been about taking apart superhero tropes and putting them back together in situations atypical of the genre (1). But Moore went a few steps further here because he was able to sully the intellectual property and express his own politics about the concept. And he did it beautifully—Watchmen transcended the form with its intricate plot and a reverberating flow of prose and art. All indisputable.

Regardless of his intentions, however, Moore built a thematic framework that bolsters many awful superhero tropes—and these have outlived the subversive qualities of the text (2). Moore, to his credit, created dynamic three-dimensional characters, and that’s the problem. After all is said and done, Dr. Manhattan is a mass murderer indifferent to human suffering. Rorschach, a proto-incel, is an Alex Jonesian conspiracy-fabulist. And yet fans—like me—loved them both for decades. Moore had us spend so long in the heads of Manhattan and Rorschach that eventually their world-views became compelling.

Omar deftly explicates the comic’s whiteness, and its failures to address race and racism (despite its aims and goals), and ties this to a general pro-police tenor in Moore’s work—surprising, to be sure, in an anarchist; less so, perhaps, in a writer of superhero comics: and this, I think, is where the dam’ whole enterprise falls down: “The fail condition of subversion/parody is reification.”

But I want to dig into one thing Omar brings up that reveals just how heartbreakingly Watchmen fails, or was failed—

Rorschach is every bit the reactionary Miller’s Batman is, but Moore’s superb narrative tells us why in a compelling and heart-breaking flashback. Ironically, Rorschach’s lengthy existential thought balloons (and those of Dr. Manhattan) feed into conservative ideas about a dark nature of humanity with a far greater lasting effect than Dark Knight Returns. Moore compounded this by taking Rorschach’s side in philosophical debates. When a “liberal” African American prison psychiatrist must treat Rorschach, it’s Rorschach’s perspective that infects him, not the other way around. Rorschach is shown to have the more compelling, self-aware view, while the psychiatrist is a liberal fop, as weak as Rorschach implies when he reads him. Moore—unlike Miller who actually got worse (3)—moved on from treatments of superheros in the decades after Watchmen, I suspect because he recognized the perils of even engaging the tropes (4).

Aaaaand—I mean, it’s not that this isn’t not what doesn’t happen, and it’s not that Dr. Malcolm Long isn’t a liberal fop, a milquetoast, even, and it’s not that he’s not infected by Rorschach’s nihilism. But that’s not the end of Long’s story.

Rorschach’s (Kovacs’) “compelling and heart-breaking flashback” is, of course, built around, based upon the Kitty Genovese story—not what actually happened, but the story—

(And as a brief digression, the shot here, of neighbors watching from the balconies of apartments supposedly on Austin Street in Kew Gardens, Queens, New York, lends some slim credence to the mildly contested theory that Moore tripped over the story of Kitty Genovese by way of Harlan Ellison’s “Whimper of Whipped Dogs,” which, I mean, I know I first heard the story of Kitty Genovese by way of an Ellison essay, I think, in The Glass Teat, I think, which is one more I owe the bastard, and anyway, I agree with Joanna Russ—but let’s face it, the story of Kitty Genovese is everywhere.)

(And as a brief digression, the shot here, of neighbors watching from the balconies of apartments supposedly on Austin Street in Kew Gardens, Queens, New York, lends some slim credence to the mildly contested theory that Moore tripped over the story of Kitty Genovese by way of Harlan Ellison’s “Whimper of Whipped Dogs,” which, I mean, I know I first heard the story of Kitty Genovese by way of an Ellison essay, I think, in The Glass Teat, I think, which is one more I owe the bastard, and anyway, I agree with Joanna Russ—but let’s face it, the story of Kitty Genovese is everywhere.)

—though I must admit a moment’s amusement, reconciling the queer bar manager who was, with the socialite who was supposed to have been, who rudely rejected the pop-art op-art dress that ended up becoming what would be Rorschach’s mask.

It’s pointless to argue whether 38 or “almost forty” neighbors really heard the socialite’s screams, or if it was more like what really happened; what happened that was compelling and heartbreaking was that Kovacs read an article in the New York Gazette that said that’s what had happened, which is what inspires him to make his mask and dress up as Rorschach and go and fight crime as a costumed adventurer né superhero—“I knew what people were then,” he tells Dr. Long; “behind all the evasions, all the self-deception. Ashamed for humanity, I went home. I took the remains of her unwanted dress and made a face that I could bear to look at in the mirror.”

And Dr. Long hears that and tries to dismiss it and feels badly about trying to help Rorschach or Kovacs out of somewhat selfish reasons and has movie-of-the-week arguments with his wife about the damage his dedication to his job is doing to their marriage, and in the end he breaks on the bulwark of Kovacs’ or Rorschach’s next, real origin story, which I bet Zack Snyder got a kick out of filming—but that isn’t the end of Long. It’s just the end of chapter six. (Of twelve.)

No, Long’s end comes at the end of chapter eleven: as Ozymandias’s stupidly huge plot comes to fruition, a number of uncostumed unadventurous unsuperheroes whom we’ve seen here and there in the previous chapters milling about the business of their lives as the protagonists protagonize, these folks end up converging on a corner by Bernard’s newsstand near Madison Square Garden, Dr. Long, and Bernard (of course), and Bernie, Derf, Detectives Steven Fine and Joe Bourquin (cynical cops who in the end get to prove they’re good police, but I anticipate myself), Milo, Gladys Long, and Joey and Aline, and the point is, what happens is, when Joey and Aline get into a fight over their dissolving relationship, and when Joey attacks Aline, pushes her to the ground, starts kicking her, right there, on the sidewalk, before the newsstand, all those onlookers, those neighbors, less than 38 or almost 40, sure, but Bernard and Detective Fine and even yes Dr. Long, despite his infection with Rorschach’s nihilism, he steps up with the rest of them all to stop the fight, and that’s the end of Dr.Long, and all of them: a spontaneously anarchist fellowship, a striking reversal of a superheroic origin, a repudiation of all the cool grimdark Rorschach supposedly serves up as truth, a pro-Genovese anti–Genovese-story—

—that gets smashed in the very next instant, bigfooted by the squid-drop climax of the protagonists’ plot.

But! This ironic thematic climactic crescendo itself gets bigfooted by everything that happens around and about that squid-drop: the superhero-cool in Antarctica, “I did it thirty-five minutes ago,” Dr. Manhattan’s apotheosis and Ozymandias catching bullets and Rorschach in the snow. The book’s supreme irony—that the human fellowship Veidt despaired of is obliterated precisely by the plot that Veidt engineered to restore it—is itself ironically overwhelmed by the superheroic armature of that plot. So much so that almost no one who talks about it ends up talking about this at all…

I said this recently but I think the best part of the comic is all the background characters coming together to try to stop a fight in Times Square, on their own, no capes. https://t.co/iuyO0U5vMe

— Gerry Canavan (@gerrycanavan) December 9, 2019

…so that’s another way that Moore and Gibbons failed the comic (not so much Higgins, he’s still cool), and the comic failed the show, and the show failed us all, and as for us?

The Fanonian Watchmen is there, but buried deep. By quoting from the “The Internationale,” Fanon’s title gives to the Wretched of the Earth the implied imperative to “Stand up,” but Lindelof’s Watchmen submerges any revolutionary consciousness under things like the cartoonish “Red Scare” character. The only masses in the show are white supremacists. Still, if you look for it, you can find in the story of Angela and her grandfather the discovery that America’s problem is not hidden conspiracies to be revealed but the open secret of American white supremacy; if you want, you can trace out the show as it might otherwise have been, in which two granddaughters of American massacres team up to create a better world from the ashes of what was done to their families.

We’re left once again to ignore the ending we’ve been given, and imagine something else.

(Oh but one last ever-loving thing: learning that Lady Trieu’s villainous genius was explained and excused by her descent from Veidt was enough to make me want to throw the goddamn television show across the goddamn room. Why—that would be as astoundingly short-sightedly stupid as the Star Wars people deciding that instead of being her own person, Rey would have to be excused and explained by her descent from someone like Emperor Palpatine, I mean, can you imagine? —Can you imagine something else? Something different? —At all?)

Retrospectacular!

It’s that time of year, when those of us still in the blogging game tell you what we did with the previous three-hundred-sixty-five, much as many of us working the fantastika mines tell you which of what we’ve done is eligible for this award, or that. —But most of what I’ve done this past year has been over at the city, finishing the third volume; writing the thirty-third chapter. The blogging here’s been slight.

But it’s also that time of the decade, isn’t it? —Accepting for the moment that one can at once aver that decades don’t begin on the downbeat of the zero,

Let’s see: I made an opaquely definitive statement on URBAN FANTASY, that I later repurposed as a guest-post in a marketing push for vol. 2 (I have some strange ideas on marketing); I solved in one stroke both income inequality and global warming; I defined the most important social media trend of the decade (which promptly dissipated); I engaged in some criticism, like this, about Frozen, or this, about, um, Frank Herbert, and Reza Negarestani, or this, which is about just about everything, and had a DVD’s worth of cut scenes; and also I used the supreme cinematic accomplishment of 2008 to explain the Cluthian triskele; and also I had some things to say about publishing (mass-market, and self-); a friendly comment from an international correspondent led to a momentary spark of reason; I walked away from Twitter, which was supposed to lead to more blogging (I mean, it did, but not as much as maybe I’d thought, and also, see above); and, but, before I did, I turned some off-hand twitterings to things I rather liked, on novel-shaped objects, and galactic civilizations.

Also, I sold maybe the only story I’m going to sell, and—even though I got started before 2012, or even before the beginning of the decade, still: I published all three books in the past ten years; I wrote a goddamn trilogy. —So there’s that.

Minimally viable product,

or, Easy money at the ketchup factory.

“The books are wretchedly written, but fast-moving. The wretched prose, the mixed syntax, the bad grammar, and the typos would barely raise a sneer from the MFA-educated crowd. They’re used to a publishing industry that already embraces James Patterson and Dan Brown’s barely literate level of storytelling. The bar was already low; it’s just being slid through the wood chipper and scattered over the culture like salt at Carthage. —I looked up Anderle’s record on Amazon. His Author Rank is #54 in the Horror category, placing him ahead of Lee Goldberg, Seth Grahame-Smith, and some guy named “Richard Bachman.” In Science Fiction, he’s ranked #60, ahead of Alan Dean Foster, John Scalzi, Douglas Adams, and Neal Stephenson. —But if you feel that Anderle’s work represents the bottom of the barrel, you haven’t met T.S. Paul.” —Bill Peschel

Fuck death.

It hit me hard when Howard Cruse went and died, but I’d had no idea Tom Spurgeon was already gone—

This storm is what we call progress.

Many of the great fantasy writers of the last century were shaped by the experience of World War One; the attitude of JRR Tolkien to the world storm of his time is anguish and anger; he and other great fantasy writers turn away from the world to shame it. Here are the four phases:

- Wrongness. Some small desiccating hint that the world has lost its wholeness.

“With each set of three books, I’ve commenced with a sort of deep reading of the fuckedness quotient of the day,” he explained. “I then have to adjust my fiction in relation to how fucked and how far out the present actually is.” He squinted through his glasses at the ceiling. “It isn’t an intellectual process, and it’s not prescient—it’s about what I can bring myself to believe.”

- Thinning. The diminution of the old ways; amnesia of the hero and of the king; the harvest fails, the Land dries up; diversion of story into useless noise; battle after battle.

After The Peripheral, he wasn’t expecting to have to revise the world’s F.Q. “Then I saw Trump coming down that escalator to announce his candidacy,” he said. “All of my scenario modules went ‘beep-beep-beep—super-fucked, super-fucked,’ like that. I told myself, Nah, it can’t happen. But then, when Britain voted yes on the Brexit referendum, I thought, Holy shit—if that could happen in the UK, the US could elect Trump. Then it happened, and I was basically paralyzed in the composition of the book. I wouldn’t call it writer’s block—that’s, like, a naturally occurring thing. This was something else.”

- Recognition. The key in the gate; the escape from prison; amnesia dissipates like mist, the hero remembers his true name, the Fisher King walks, the Land greens. The locus classicus of Recognition is Leontes’s cry at the end of The Winter’s Tale (1610) on seeing Hermione reborn: “O she’s warm.”

In the hall, he relieved me of my misjudged chore coat, and handed me a recent reproduction of Eddie Bauer’s 1936 Skyliner down jacket: a forerunner of the down-filled B-9 flight suit, worn by aviators during the Second World War. Boxy and beige, its diamond-quilted nylon was rigid enough to stand up on its own. When I put it on, it made me about four inches wider. Gibson shrugged into a darkly futuristic tech-ninja shell by Acronym, the Berlin-based atelier, constructed from some liquidly matte material.

“You have to dress for the job,” he said.

- Return. The folk come back to their old lives and try to live them.

She doesn’t zoom through glowing datascapes; instead, having suffered from “too much exposure to the reactor cores of fashion,” she practices a kind of semiotic hygiene, dressing only in “CPUs,” or “Cayce Pollard Units”—clothes, “either black, white, or gray,” that “could have been worn, to a general lack of comment, during any year between 1945 and 2000.” She treasures in particular a black MA-1 bomber jacket made by Buzz Rickson’s, a Japanese company that meticulously reproduces American military clothing of the mid-twentieth century. (All other bomber jackets—they are ubiquitous on city streets around the world—are remixes of the original.) The MA-1 is to Pattern Recognition what the cyberspace deck is to Neuromancer: it helps Cayce tunnel through the world, remaining a “design-free zone, a one-woman school of anti whose very austerity periodically threatens to spawn its own cult.” Precisely because it’s a near-historical artifact—“fucking real, not fashion”—the jacket’s code can’t be rewritten. It’s the source code.

I think it’s inarguably clear: we must admit William Gibson to the ranks of the world’s great fantasists.

Regret, by definition.

I’m not sure what to say about this article about the reappearance of John M. Ford; chances are good you’ve already seen it, since it’s been out for almost a week now, and it shows up in the wee little sidebar on the Google news thing, which I assume means people want to see it enough that the algorithm has learned it’s what people want to see. —But I’m not gonna not put a link to it here; the days I don’t want to be Dorothy Dunnett when I grow up, I want to be John M. Ford; every time somebody quotes his line about his horror of being obvious, I feel entirely too seen. Maybe wind this up with a growl at, I don’t know, the Yankee health insurance system, or capital’s grinding gears, or pettily familial stupidities redeemed by an accidentally incandescent burst of good news: send tweet.

What I tell you three times is true.

The thirty-third installment’s been released: the eleventh (and final) chapter of the third volume, which means: I’ve done it. I’ve gone and written a trilogy.

And there’s work yet to be done and technical difficulties to overcome and I have to re-remember all the stuff about marketing and distributing book-shaped objects but for the moment I get to sit here on this deserted bit of beach as the tossing storm growls away over the horizon and take a deep breath and enjoy the silence, before I start vaguely to worry about what happens next. (An aftermath, yes, I do enjoy a good aftermath, but then what? And what then?)

—I guess I’d thought a Snark would have more meat on it?

—30—

“This is the violence that endings do to stories,” says Aaron Bady, writing over at Dear Television about the final season of Game of Thrones; come for his epic musings about the longue durée, sure, which get at how we go about doing what we do, but stay as Sarah Mesle namechecks the smoldering appeal of Tanthalas Quisif Nan-pah, which gets at some of the all-important why—wait a minute. Strike that. Reverse it; thank you. (—The commenter who insists “you cannot directly comment on the real world with fantasy and every one who thinks so is a pompous idiot” would be the lagniappe.)

Offensively impeachable.

“Ultimately, acting White House chief of staff Mick Mulvaney seemed to have been able to talk the President out of closing the port of El Paso […] After the President left the room, agents sought further advice from their leaders, who told them they were not giving them that direction and if they did what the President said they would take on personal liability […] ‘He just wants to separate families,’ said a senior administration official […] ‘At the end of the day,’ a senior administration official said, ‘the President refuses to understand that the Department of Homeland Security is constrained by the laws’.” —And this, more than the election interference and the emoluments and the graft and the et cetera (though those too!) but THIS, this nightmare is why he has to go, and go now.

Catastrophic injury and sudden death have been known to occur.

Those Go Army commercials they’re showing all the time on Hulu now, there’s the one where a fire squad or a platoon or whatever crashes their choreographed way through an otherwise empty neighborhood troped up to read as GENERIC MIDDLE EASTERN HOTSPOT, firing guns at everything but each other, or the other one, where a cavalry unit of jeeps encrusted with soldiers charges across a field, and helicopters keep pace overhead, and every gun held or mounted shoots rapidly repeatedly wildly ahead at something we never see, stitching the sky with Star Wars light, and all the while in both commercials this calm cool collected authoritative voice stirringly intones platitudes of altruism and sacrifice, of service to those in need, of the best America has to offer, it’s all just as completely dizzyingly incoherent as those other commercials they show on Hulu all the time, full of people out living their best lives, smiling with ostentatious magnanimity as they forego this or that limitation previously imposed by implied, otherwise unseen conditions, and all the while this clipped and business-like authoritative voice rapidly monotones the endlessly specific side effects of whatever miraculous pharmaceutical it is that makes all this wonderment possible; “Do not take Qurac if you are allergic to Qurac.” —The hard power, and the soft.

Mister Blue Sky, please tell us why.

“Teens and young adults are in the midst of a unique mental health crisis,” we are told, and of course we’ve got to go and blame it on their use of smartphones and social media, tsk tsk, and not the fact that, say, nobody older than them seems to give a shit that we’re literally burning the clouds away.

A moment of your time.

Over at the city, the thirty-second novelette is appearing this week, and next; the penultimate chapter of the current volume, the third, which we’re calling In the Reign of Good Queen Dick.

And I know what you’re thinking: Kip, thirty-two novelettes—that’s a lot! —But you count it all up, it’s only 484,470 words, in toto, so far: considerably less than two Songs of Ice and Fire. (It’s also just over one Lord of the Rings; 44% of a Harry Potter; 15% of a Wheel of Time, or a Malazan Cycle, though it’s 50% of a Marq’ssan; 28% of a House of Niccolò; and 210% of a Valley of the Nest of Spiders.)

So it’s not that much, in the scheme of things. You could probably get all caught up before I’m done posting this one.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that a single person in possession of a billion dollars must be in want of dismantlement.

“It is always a little sad to see what the people rich enough to have everything actually want,” says the article, and truer words; truer words.

Just wrestle me.

“For such a physical sport, some men may express concerns over applying force on a woman or pressing against a female opponent in the era of the #MeToo movement,” says the article, and what bizarre creatures, these men-who-may, who seem utterly bereft of concepts of context and consent…

“This was back in 1945.”

Well, I was working in a dental office on Lexington Avenue for two brothers, JD and JL Burke, and all morning long people would come in and say there seems to be rumors that the war is ending. And since I wasn’t very far from Times Square, I could just walk over there and see for myself. And so after my bosses came back at 1:00 from their lunch hour, excuse me, I went straight to Times Square where I saw on the lighted billboard that goes around the building, V-J Day, V-J Day, and that really—that really confirmed what the people have said in the office. And so suddenly I was grabbed by a sailor, and it wasn’t that much of a kiss, it was more of a jubilant act that he didn’t have to go back, I found out later, he was so happy that he did not have to go back to the Pacific where they already had been through the war. And the reason he grabbed someone dressed like a nurse was that he just felt very grateful to nurses who took care of the wounded. And so I had to go back to the office, and I told my bosses what I had seen. And they said, Cancel all the appointments, we’re closing the office. So they left, and I canceled all the appointments and went home.

—Interview with Greta Zimmer Friedman, August 23rd, 2005

SARASOTA—George Mendonsa hasn’t even been buried yet, but a statue depicting the World War II veteran kissing a woman in Times Square to celebrate the end of World War II has been vandalized in Sarasota.

The sculpture called “Unconditional Surrender” was spray-painted with #MeToo graffiti, indicating the movement founded in 2006 to help survivors of sexual violence.

While the statue—which came to Sarasota in November 2009—represents nostalgia and a level of unity and pride, some consider the act a sexual assault by today’s standards.

—“#Metoo” painted onto “Unconditional Surrender” statue in Sarasota

Greta Zimmer Friedman:

Well, we met in Times Square in 1980.Patricia Redmond:

But who invited you to Times Square then?Greta Zimmer Friedman:

LIFE Magazine.Patricia Redmond:

Okay. And?Greta Zimmer Friedman:

And we sort of—I didn’t want to reenact the kiss. First of all, my—well, no, my husband did not come with me, but his wife was there.Patricia Redmond:

Mr. Mendonsa’s wife?Greta Zimmer Friedman:

Yes.Patricia Redmond:

Well, she was there the first time.Greta Zimmer Friedman:

Well, I didn’t know. Well, it wasn’t—it wasn’t my choice to be kissed. The guy just came over and kissed or grabbed.Patricia Redmond:

This was back in 1945.Greta Zimmer Friedman:

Yes.Patricia Redmond:

Okay. So now we’re in 1980, and we do a reenactment of the kiss.Greta Zimmer Friedman:

Yes. I told him I didn’t want to redo that pose.Patricia Redmond:

Well, we have—we have the picture here.Greta Zimmer Friedman:

It’s sort of a—Patricia Redmond:

And it’s kind of the pose, and it says—and the sign, this is Times Square.Greta Zimmer Friedman:

Right.Patricia Redmond:

It says, what does it say on the sign?Greta Zimmer Friedman:

It says, “It had to be you.”Patricia Redmond:

Okay. So that makes it pretty official, doesn’t it?Greta Zimmer Friedman:

I would guess.

—Interview with Greta Zimmer Friedman, August 23rd, 2005