The Reproof Valiant.

You realize, of course, that “the art of the possible” isn’t the art of doing what’s possible. It’s the art of making things possible.

You never forget your first.

An offhanded comment becomes a meme, suitable for bloggers of a Certain Age: when did you make your first “Christ, what a right-wing hack” post about Instapundit?

And in the comments over at Unfogged, a meme becomes, well, any of a number of things. I keep forgetting how vociferously active that joint is. Makes me wish I hung out in comments more. —But there’s a nice thick strand of how-did-you-end-up-in-blogging there, namechecking poliblogs of days of yore (and to realize that Body and Soul and Fafblog! now belong only to yore is icily sobering) and the folks who’ve been around long enough to remember what blogs were like before they became a corner soapbox in the marketplace of political ideas mention Rebecca’s Pocket and /usr/bin/girl to general befuddlement.

Me? The first thing-that-is-a-blog I read was David Chess’s, which is usually called The Curvature of the Earth is Obliterated by Local Noise, when it isn’t called David Chess’s blog. From him I found Textism, and Oblivio, and Anonymous Juice, and Anita Rowland, and Flutterby, and other, less reputable folks, and then I went and started my own. (Before all that, I’d spent a lot of time on Plastic, wondering why I couldn’t get an account on MetaFilter. Then I discovered I did have an account on MetaFilter, which I don’t remember having set up. But the password worked. I still haven’t used it. Since I have a blog and all. And anyway, I was never very good at the whole hipshot quicklink thing. —Though the mix-tape post that MeFi arguably started, and snarkout definitely perfected, is something I wouldn’t mind doing more of.)

LiveJournal came (much) later. (And all that that entails.)

Of course, if you’re not of a Certain Age, or’d rather not reflect on it, you could always celebrate the news we can finally announce: Dicebox is being made into a movie. (There’s even a novelization!)

The all-too-common tragedy of the foreseeable unforeseen.

As a Republican state senator in Montana and as a human being, I am offended by Senator Craig’s existence. Why oh why are most of the perverts that get caught Republicans? Are there more of them or are they just stupid? The thought of a US Senator chasing love in all the wrong places makes me think longingly of the Ayotollahs in Iran. They would just kill the turkey.

And James, Dave Lewis, a very honorable man, did not recommend “death for queers” (your phraseology).

His statement was obviously exaggerated, but I am sure he meant only to display his rage at Craig’s betrayal of his word and the trust placed in him.

Most weeks, three or four people are hacked, stoned, burned or shot to death for being lesbian, gay, bi or trans. The highest Shia religious dignitary Sistani has again promulgated a fatwa calling for the execution of all non-repentant LGBT people—people talk of him as a liberal and in this degree he is—he allows people to repent on pain of death when most of his rivals would just kill. Contacted by the UN about this campaign of murder, the Iraqi government has refused to acknowledge that it is even a problem.

This is a direct consequence of the war—the Saddam regime, vile as it was, was secular in this respect, just as the Ba’athists in Syria still are. No-one does well in a totalitarian state, but LGBT folk were left alone, mostly.

Those who survive, flee. Through a network of safe houses and incredibly brave people and escape routes to the West.

The British home office is disinclined to regard the likelihood of being murdered by a variety of non-state agents as persecution, because it is not the government that is doing it. The leaders of the diaspora queer community are under death threats—again from Sistani—and live under police protection of a moderately minimal kind.

When troops leave, as leave they will in the runup to the British and American elections, there will be no change, except possibly for the worse.

One of the diaspora spoke to us at Translondon this evening.

He said something amazingly moving to the effect that this is not a movement of Resistance so much as a movement of Existence. Because when everyone wants to kill you, staying alive is the most radical form of resistance possible.

Not sure how that happened.

It’s not like I meant to take the month of August off or anything.

We the motherfucking people.

The Edwards campaign will send our forgetful Attorney General a copy of the constitution for every signature they receive on this petition. (Then again, maybe some of those copies could go elsewhere…)

Commutation.

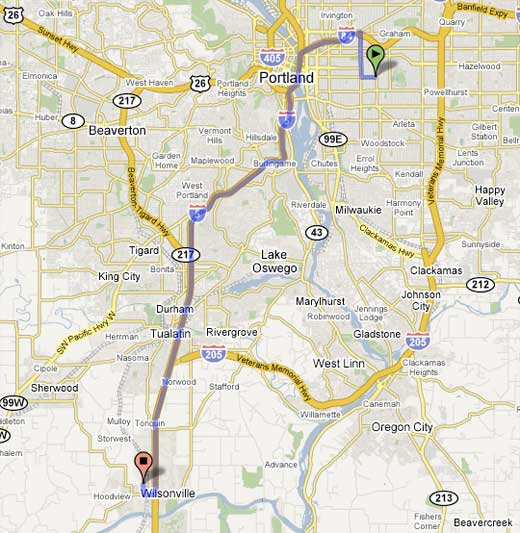

I drive to work these days. Didn’t used to. —When I was freelancing, I’d drive to the occasional client’s office, and there was that month or so temping at Johnstone, and the couple of weeks writing a technical manual for PetSmart, and they’re both out by the airport. Oh, and the week or so at Rio, over the river in Vancouver, laying out cards that advertised the music pre-loaded on whatever MP3 player they’ve probably stopped making by now.

But I’ve almost always otherwise been able to bus or subway or walk to work, usually. For almost five years in this house with the job I’ve had I could walk downtown some mornings, four miles, an hour and a half.

The job moved; now I drive.

And on the one hand, so what? Most people in this country drive to work. Yeah, I say. That’s right. —And now I know why most people in this country are so blackly sullen and ashily angry, and maybe even why we elected Geo. W. Bush to the presidency. (The first time, if not the second.)

There’s a luxury to going to work under someone else’s power. (Or on your own feet, but that’s a luxury of a different order.) —Twenty minutes or so yet to read, doze, listen to the iPod, people-watch, think, write, pretend to think or write while actually people-watching. Driving, I may be master of my fate and captain of my soul, but I must be paying attention, all of it, for the half-hour to forty-five minutes (to an hour, to an hour and a bloody half with the Burnside closed and a stall on I-5 northbound backing up traffic over the Marquam and the regular line of people trying to get on the Sunset snarling the 405). No dozing. No reading. No writing. Barely any thinking, because what the fuck are you trying to do would you get over and let me Jesus! —And the people-watching sucks.

At least I can hook up the iPod to the stereo. (The joys of autonomy!)

The next-to-last straight stretch of I-5 between Bridgeport Village and Wilsonville is as-yet undeveloped; the 205 is the only interchange. Otherwise it’s trees and trees and sixty-five-mile-an-hour speed-limit signs. The median’s a wide strip of dusty yellow grass (this time of year) with a low wire fence running right down the middle. —And then you hit the last straight stretch, lined with hesitant office parks and anemic car dealerships, whose hinterlands are marked by the Garlic Onion restaurant in the basement of a Holiday Inn, its iconic sign spearing up past the overpass as you come around a bend out of the trees.

This morning, running down those next-to-last two miles of tree-lined highway, I spotted a work crew in the median, laying out safety cones and orange lights and white barricades. The barricades they were leaning up against the low wire fence, and every other one had a sign on it. The signs all said NO PARKING.

Okay. Easily enough done—

I’ve mentioned it elsewhere and otherwise, but I might as well note it here, too, seeing as how and all: The “Prolegomenon” of City of Roses has been published in the Summer issue of Coyote Wild. If you haven’t read it, go, read it, if you like; if you have, well, go read it again, why not; either way, go, enjoy some beerly free speculative fiction.

More on the behemoth.

Dylan, as ever, says it best. —Meanwhile, Momus is trying to take the piss out of Potter and The Wire at the same time, and for such an intellective jackanapes falls distressingly flat. Announcing to the world that you think the point of a name like Severus Snape is “you don’t have to waste much time working out whether they’re good or evil” is to mistake the set-up for the punchline, and if you require nothing more than a weepy third party’s word to accept that Bubbles must be “the most sympathetic character ever to appear in a TV drama,” well, you’re pretty much doomed to repeat the downfall of Tom Townsend, who never read novels, just good criticism, thus to efficiently garner the thoughts of a critic as well as the novelist.

—Ah, well. Momus is not without his point re: “wholly human,” and at least it’s—wittier? more insightful?—better than Ron Charles’ weary screed about how it’s all not really, you know, reading.

Eight hours and 759 pages later.

Well. That’s done. —Next?

A pier appears.

—courtesy of the Spouse

The power of names.

No, Barkley; no. You can cite Juan Cole all you want, but this decade will not be called the zeroes, or the naughties, or the naughts; not even the old-skool aughts. It’s going to be a little more cumbersome: the aught-naughts. As in, “We really ought not to have done that—”

—racing down tracks going faster, much faster—

Immanentise the eschaton!

You let the eschaton alone. It’ll come in its own good time.

—Competing grafitti noted in the neighborhood of I want to say Glastonbury

Set out, set out. —But there’s a couple of things that ought to be explained first, like how magic works; right now, I want to talk about a hitch in the body of time. Lord Fanny and King Mob, drawn by Jill Thompson, hanging out in a diner:

And it is, isn’t it? Getting faster. All the time.

But this has nothing to do with eschatons or apocalypses, armageddim or fifth suns. There’s no damn whirl; no damn pool. It’s all so much simpler than that. There’s just us, and here, and now, and the aforementioned body of time. —The thing about time being that your immediate, visceral sense of it, the time that has actually flowed over and past you, your experience of it, your experience, well, that time is always the same size and the same shape, once it’s set (and rather early on): it’s always the size of your life. (“No more, no less,” to tap another echo elsewhere.) As you get older, as you pack more hours and days and years into the same little box, each one is necessarily left with a smaller slice of the whole.

Pitiless, perhaps, but that’s math for you. —“See,” said my littler sister, when she told me this, “a year is like a twelfth of my life. But it’s like a twenty-fourth of yours.” Grinning like a canaried cat in the back seat. (She had every reason to, of course. Already my years were smaller, harder to see, easy to lose in the crowd. It’s only gotten worse.) —Of course everybody King Mob speaks to has been saying the same thing. Everyone ever has always said the same thing. It’s always already been getting faster.

Keep this hitch in mind, and you’ll be able to answer certain questions like a chuffed Robert Graves: why there’s always jam tomorrow and jam yesterday, for instance, and never jam today. Why every Golden Age is the same Golden Age, and where the Old Skool was; when the Eschaton will strike; where Armageddon will have been.

Forget it, and you fall prey to the anthropic fallacy—the lie of the one true only. Like a smug Frank Tipler, you’ll think that here and now is special because you’re here and now; you’ll think you can say for sure when the jam will arrive; you’ll believe it’s all finally coming to pass and in your time; you’ll know in your bones that time is actually getting faster, because every year to you seems shorter than the year before.

The funny thing about The Invisibles is that while the plot depends upon this fallacy—time really is speeding up, just as Fanny says; the age of the fifth sun is about to end in whirlpools and apocalypses, and the crowning of a dark Lovecraftian king in Westminster Abbey during a solar eclipse—but the point of The Invisibles is precisely opposite: we all immanentize the way we die: alone. Our initiation is always already about to begin; it’s never not the Day of Nine Dogs, and Gideon’s last phone call is the same as Wally Sage’s, to tap another echo, elsewhere again. (Or Jack Frost, with Gaz in his lap. —Of course there’s a plot! Of course the plot must have such a ridiculous, action-packed climax! It’s all a game, remember? Sucked from an ærosol can. Go back and play it again!) —The fact that you’re in the here and now doesn’t make this here, this now any more special than any other slice of eternity—except, that is, of course, to you. And every hour that passes you by makes every other hour that much the smaller, the faster, much faster, until they never let us out ten blocks later.

—Thus, the hitch in the body of time.

I’m hurting cultchah!

Confidential to Keen in Silicon Valley: dude, I know, he made a lot of money, but you start citing George Lucas as some sort of, Christ, I’m not sure what, a compeer of David Hockney or something, some sort of authority on art, well, you’ve pretty much gone and shot your argument in the face. (via; via)

What do you think of Internet video? Lucas says there are two forms of entertainment: circus and art. Circus is random, he says: “feeding Christians to the lions”—or, he says, as the term in Hollywood goes—”throw a puppy on the highway. … You don’t have to write anything or really do anything. It’s voyeuristic.” In short, he says, it’s YouTube. Art is not random, Lucas says. “It’s storytelling. It’s insightful. It’s amusing.”

Harry Potter and the Lost Light.

I had no idea. I honestly had no idea. (via)

All models are wrong. Some are useful.

We’re finally watching Rome. —At some point during the second episode, I say something like, “So it’s Artoo and Threepio.”

And then a little later, the Spouse says, “I’m still trying to deal with the idea of Threepio as a whoremonger and Artoo as a stolid family man.”

I frowned. “No, wait,” I said. “Threepio’s the uptight prig, right? Artoo was the id-guy.” The collapse and reversal shorted something in my brain. I grinned. “So, like, Molly’s Threepio, right?”

—Maybe you had to be there.

Magical white boy.

Oh, hell, let’s chase the red herring for a minute. I’ve got time; I’ve got nothing but time. —So: no. Morpheus is not a magical negro. If nothing else, his touchingly stubborn faith in Neo, which sets him at odds with the magical Oracle, which causes us to doubt him (though we never doubt he’s right: Neo must be the One—look at his name!), and which even causes him to doubt himself—this grants him a degree of agency and protagonism that sets him apart from the mere role of wisely aiding and abetting Neo’s enlightenment. (To say nothing of his captaincy, his popular acclaim in Zion, or the fact that he’s the one who lives to tell the tale—)

So: the One True Neo, a man with almost no past, prone to criminality and laziness, inwardly disabled by his shyly geeky nature, hated as a hacker by the powers that be, granted a terrible power so close to the very nature of things yet tempered by his need to help others, ultimately sacrificed, and all to aid Morpheus in realizing his dream—

Well, yes. That’s why the movies, flawed though they indisputably are, nonetheless have the power they have.

But I wasn’t really thinking about the red herring. I was thinking about Mercutio, and I was thinking about Nick.

—Why was I thinking about Mercutio? Right. Because we’d just finished the second season of Slings and Arrows, with its hilarious production of Romeo and Juliet running under and around the A-plot of Macbeth. Why was I thinking of magical negroes? Because I’d stumbled over MacAllister’s LiveJournal, and the most recent entry over there is a nice-enough trip through the trope. And why was I thinking of Nick?

Well, first, Mercutio; specifically, given the confluence of topics, Harold Perrineau’s, in the deliriously ludic Baz Luhrman production. Ostensibly Romeo’s foil, Perrineau’s Mercutio practically foils the whole damn film, othered to his very gills: the only black character, his gender bent in an otherwise rigidly stratified world, his sexuality—well. Even the lightest brush of those buttons with Mercutio—witty, articulate, prancing Mercutio, always a snappy dresser—leaves little room for doubt. —Forever outside the discourse of both those houses, he pushes and pulls and chides his charge until Romeo sees the light and gets off his goddamn ass, and as far as magic goes, well. Queen Mab, bitches. Those drugs are quick.

But hard as they might push in that direction, and as much power as they might arguably draw from the trope, and despite his Act III Scene 1 sacrifice, there’s no way in hell or out of it that Mercutio could ever be anyone’s magical negro.

(A conscious piss-take? I doubt it; I highly doubt it, if for no other reason than Spike Lee’s eponyming talk came five years later. —But Uncle Remus has been with us for a long, long time. Even in Australia.)

Nick, of course, Chris Eigeman’s Nick, is the Mercutio of Metropolitan, othered by his cheerfully chilly snark, his abiding concern for times and fashions past, his detached perspicacity—though perched in the very catbird seat of privilege, he is nonetheless, within his own context, his insular circle, despised; though his power is mighty (he creates a person from whole cloth, like New York magazine) and his scorn withering (ask a bard what terrible magic satire can wreak), he does little beyond push and pull and chide his Romeo, Tom Townsend, over the barest threshold of the story. (He does also insult a Baron, and start a cha-cha.) —And though he isn’t sacrificed, per se, he does abruptly leave the story toward the end of the second act (of three, of course, not five), marching stoically off to his comically supposéd doom.

But much as it might tickle me to push this WASP in that direction, there’s no way in hell or out of it that Nick could ever be a magical negro.

And not because he’s so very, very white. Well, yes, of course, but—

Nick’s a foil, like Mercutio: slipped under the gem of the protagonist to catch the light and throw it back, up and through the protagonist’s facets, the better to shine for our delectation; necessarily subordinate to the protagonist because it’s all about the protagonist. Isn’t it? —They are othered because the protagonist is by definition normal, and they must stand in contrast. They leave so suddenly because the protagonist, having been pushed, must in the end do it all alone. It is, after all, the protagonist’s story.

Yet ask an actor who they’d rather play.

There are foils that disappear behind their gems, that bow and scrape their way across the stage, that take so literally the story-mechanics of their function—to assist the protagonist, buff and polish them till they shine—that they reify those rude mechanics within the story itself, black-garbed kabuki janitors shoving the machina in place for the fifth-act emergence of a pure white deus, and they perform these tasks with little more than a wide wise smile to hint at a there in there, somewhere. And there are settings so rich and strange and wondrous that the very question of who is a protagonist and who isn’t becomes a trick of where your eye happens to light first, and what you make of it. —Nick and Mercutio fall within that spectrum (there is no doubt as to the protagonists of their stories: not them), yet much closer to the one end than the other: no mere enablers, but so very much themselves, so selfish that they’d never be mistaken for the help.

(And because they stand so flashily in contrast to protagonists who must, as noted, be so damned normal [though admittedly not too normal, in either case], a little of the life of the proceedings can’t help but leak out when they leave. There’s a lesson there, too: like all good blades, this stuff cuts both ways.)

—One final digressive note, which draws a little on the related though much less prevalent trope of the magical faggot (think for a moment of the queer eyes buffing and polishing their protagonist; now let’s move on), and specifically the o’erwhelming need for queer foils to die in order to balance out on some inhuman scale the racy transgressions they commit to foil whatever they’re foiling; more specifically, the storied death of Tara, from Buffy the Vampire Slayer, which Mac (most specifically) brought up in passing at the end of the post that’s one of the wellsprings for this one: well. It’s at once rather a bit less complicated than that, and rather a bit more.