In Tsaija, five kilometers out from Sovetskaya Gavan.

I have no idea what I’m going to do with this just yet—

—so into the commonplace book it goes.

It’s what you do, not who (you say) you know.

Apparently, I’ve been web 3.0 for a couple years now. Who knew? (—Web 4.0, then: we all leave our websites to languish, gathering dust and rust and rotting links.)

Taran plus five weeks and counting.

I did mention the whole kid thing, right?

—Oh, sure, over at LiveJournal and Twitter. —But here? On my own dam’ blog blog? Bupkes for weeks on end. Where did the time go?

Further bulletins when I can find the words. (I know I left them around here somewhere.)

It’s the little things, isn’t it. It’s always been the little things.

“Lately, we all need to eat dinner together. Different groups, but always groups. Long tables, long meals. Lots of dishes and drinking glasses and laughing. This is not, at all, a complaint. It’s just happening on all sides now, often, and I wonder why and, also, I love it.” —Jen Snow

Stay toasty.

I’ve got to share with you, it’s like kinda providential, yesterday what happened to me. I can use this today, after that introduction from Shelly. I’m reading on my Starbucks mocha cup, okay, the quote of the day? You’ll never believe what the quote was. It was Madeleine Albright, former Secretary of State and UN Ambassador, and Madeleine has as her quote of the day for Starbucks—now she said it, I didn’t—she said, “There’s a place in hell reserved for women who don’t support other women.”

—Gov. Sarah Palin, Carson, California rally, 4 Oct. 2008

Alaska Gov. Sarah Palin’s hometown required women to pay for their own rape examinations while she was mayor, a practice her police chief fought to keep as late as 2000.

Former state Rep. Eric Croft, a Democrat, sponsored a state law requiring cities to provide the examinations free of charge to victims. He said the only ongoing resistance he met was from Wasilla, where Palin was mayor from 1996 to 2002.

“It was one of those things everyone could agree on except Wasilla,” Croft told CNN. “We couldn’t convince the chief of police to stop charging them.”

Alaska’s Legislature in 2000 banned the practice of charging women for rape exam kits—which experts said could cost up to $1,000.

—“Palin’s town charged women for rape exams”

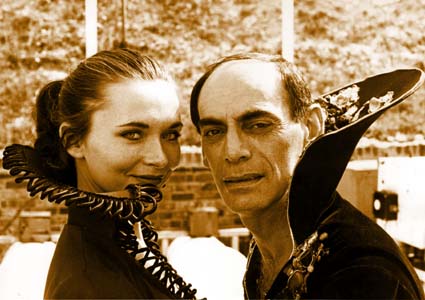

Vanity thy name is.

- Take a picture of yourself right now.

- Don’t change your clothes.

- Don’t fix your hair

- Just take a picture.

- Post that picture with no editing. (Except maybe to get the image size down to something reasonable. Don’t go posting an eight megapixel image.)

- Include these instructions.

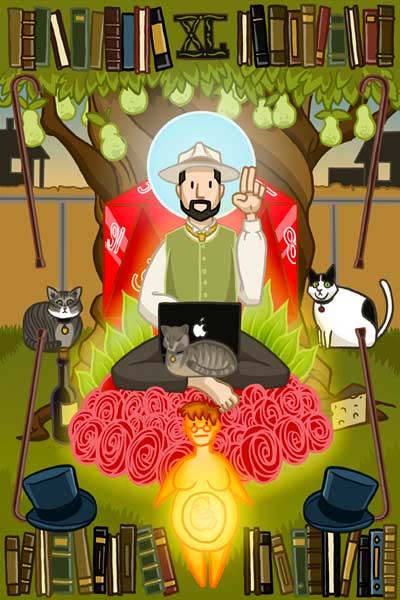

Oh, wait. That’s actually the picture what Bill gave my for my birthday. (Which was spectacular, by the way.)

—The meme’s over here, if you must know.

Andy, are you goofing on Reagan?

I swear to God, between the Sarah Palin pick (and its resulting flop-sweat fall-out) and the majestically unrepentant “Message: We Care” approach to Gustav, I’m fully expecting John McCain to accept his nomination on Thursday or whenever by reaching up and pulling off his full-face latex Tony Clifton mask to reveal Andy Kaufman, wide-eyed, blinking cherubically at the culmination of his decades-long masterstroke. —Or maybe he’s Dick Cheney. Explains a lot, don’t it.

Proper.

I didn’t watch that much television growing up, and anyway we moved a lot, so I’ve always taken the primacy of Blake’s 7 on the faith of an anglophilic SF fan. (Also, the Spouse loved it. So.) —Now, we’ve got a region-free DVD player and amazon.co.uk. We’ve worked our way up through the third episode of the second season, and it’s starting to cook, oh yes; it’s gotten as good as they said it gets. Still. I’m going to perplex the grandkids and the great-grandkids some many years from now by chuckling all unexpectedly at the recurring image of two very proper space-goths in high-cowled flowing black robes marching across an abandoned industrial depot somewhere in the middle of England with their luggage.

Why I currently like Facebook to an arguably excessive degree.

“Kip joined the groups What Would William Tanner Vollmann Do?, Scott Pilgrim is my hero and DAR: A Super Girly Top Secret Comic Diary. 10:06pm Comment”

Class warfare.

The last stop in Fareless Square on the west-bound MAX line is a city-owned Smart Park parking garage. There’s a convenience store on the first floor of the garage—one of three Peterson’s in downtown Portland.

Over across the street there’s one of those renovations where they tried gutting an old office building and turning it into a downtown shopping mall; never all that terribly successful, it recently landed a Brooks Bros. outlet as an anchor store—something hailed as genuinely “rejuvenating” by downtown business types.

Ever since, the downtown business types have been pressuring the city to evict the convenience store.

It’s a successful convenience store that makes a pretty penny for the city, holding its space for years now while other spaces about it have been rented out to fly-by-night shoe and luggage outfits and the sort of art galleries that subsidize those massive art-by-the-foot shows in Shilo Inns out by the airport. (To be fair, the Japanese restaurant and the arty-crafty gallery have been around as long as the Peterson’s.) —But in a spectacular confusion of correlation and causation, the downtown business types (who’ve hired their own private police force, and who back the reprehesible Sit-Lie Ordinance) looked at the yes, colorful and yes, occasionally noisy welter of folks that congregate about the convenience store under a parking garage at the edge of free-ride Fareless Square on the main light-rail line, and rather than—

- realizing that gutterpunks and shiftless kids and those between engagements and even the housing-deprived (among other types similarly declassé) will naturally tend to congregate in semi-public un-chaperoned roofed-over areas (like a parking garage) on or near public thoroughfares (such as a light-rail stop on the edge of a free-as-in-beer–travel zone)—where they might also purchase soda or jerky or a magazine or a newspaper, should they be so inclined;

—the downtown business types have instead decided that—

- the yes, colorful and yes, occasionally noisy welter of folks must congregate here solely for the soda and the jerky and the reading selection that’s not quite as impressive as Richardson’s or that of the public library just across the street, and the parking garage and the MAX do not factor at all in this equation, so: if the convenience store is evicted, then the colorful welter etc. will follow, and all will once more be well for the rejuvenatin’ Brooks Bros. and co.

—How heartening to discover that this “troublesome convenience store” is all that has stood between the Galleria and success. Would that all our economic woes could be salved so readily!

In addition to such spectacularly faulty logic, the downtown business types have completely forgotten everyone else who shops at Peterson’s: everyone who rides the MAX in from Goose Hollow and the west hills to shop or work downtown, and who picks up some refreshment or something to read on their way in or out. —Rather literally and demonstrably forgotten: an assistant manager of the aforementioned Brooks Bros. wrote an email to the mayor, from which we lift the following quote:

I fail to see why a disgusting store such as Peterson’s is allowed to stay open. . . . They cater to the dregs of the streets of our city.

What’s sad is, despite the money made for the city by its successful lessee, and despite the unsurprising lack of specificity in the recent flurry of complaints listed against Peterson’s (which cite only “various dates,” “various times,” and, yes, “various complaints”), the city actually seriously contemplated kicking them out—until all those “dregs of the streets” stood up and said, rather pointedly, “Hell no.” (What would the city have done had they kicked out the convenience store and noticed no drop in the noisy, colorful welter? Would afternoon commuters have sighed and blown five hundred bucks on a new blazer when they could no longer blow five bucks on a Snapple and a Wired?)

So the good guys won one, with a concession or two. Yay! —Meanwhile, if you’ve ever stepped off a bus or a subway or a trolley line and bought something at a bodega or a Plaid Pantry or a 7-11, be sure to write to Brooks Bros. and let them know what a dreg of the street thinks of their general attitude.

What do you jump after the shark?

I suppose it’s the new first you’ll never forget: your first post noting that Instapundit has egregiously burst the bounds of rational discourse. This one’s mine.

SO NOW THAT WE KNOW THAT THE PRESS COVERED FOR EDWARDS—just as, pre-invasion, they covered for Saddam—that raises a question: What else are they not telling us for fear it will hurt the Democrats’ prospects?

This is your fight.

“Reading Runes of Ragnan is like watching someone make a movie with an oiled-up weightlifter that can barely move or hold a sword after years of viewing the best fight films from Hong Kong. It’s watching a kid drop a Boston album onto a turntable in the middle of a party whose soundtrack is a mix of eclectic music culled from someone’s iPod. Its naked yearning for a kind of heroic overlay on life where everything looks awesome for a few seconds, and you can fight in a really effective way and you walk through tough guys like water and your life has mythic resonance and the most beautiful, incredible girl in the world is pledged to your heart, all says something to me that a lot of better art cannot. It makes me want to cry, this ugly but beautiful black velvet painting of a funnybook.” —Tom Spurgeon

Tags I’ve recently appreciated.

“Songs for standing still in the crowds of hurried frown people.” —I mean, Christ, have you heard this remix of “I Need a Life”?

27½ weeks out and counting.

He’d rather fight than switch.

From the eleventh paragraph (of sixty-two) of Orson Scott Card’s most recent online column for the Mormon Times:

This is a term that was invented to describe people with a pathological fear of homosexuals—the kind of people who engage in acts of violence against gays.

“This term,” of course, being “homophobe.” From paragraph sixty-one:

How long before married people answer the dictators thus: Regardless of law, marriage has only one definition, and any government that attempts to change it is my mortal enemy. I will act to destroy that government and bring it down, so it can be replaced with a government that will respect and support marriage, and help me raise my children in a society where they will expect to marry in their turn.

Emphases added. —The rest is a mish-mash of embarrassing evolutionary psychology and patently false assertions of the dictatorial rôle played by dictator-judges in dictating that the legislatures and executives of Massachusetts and California (to say nothing of the popular vote itself) must accept same-sex marriage.

I can only say what I’ve said before, to other homophobes: Mr. Card, do you not dare to presume to defend our marriage. Same-sex couples have been getting married all around us for decades, and they’ll keep on doing it, whether you manage to hold the line or not: men will kiss their husbands as you write your brave polemics; wives will continue to feed each other cake, whatever you think is right. They’ve always had the love and the cherish and the honor, and the recognition of their friends and family, and nothing you can do will take that from them. Nothing. All you can manage is to rewrite the tax code. Make it more of a grinding hassle to deal with insurance and wills. Keep loving families apart at times of illness and accident and death. Condemn children to needless, nightmarish legal quagmires. For this you would tarnish the rings on our fingers, and turn our vows into ashes.

Look to your own marriage, sir, and defend it if you must.

But leave ours the hell out of it.

Quisquiliæ.

Regrets: I regret leaving out Sara’s point from that “Comics Are Not Literature” panel about prose making you forget the black marks on the white paper, and Douglas’s complement that comics make you all too aware of these specific marks made by this specific person, and what that says about rough and smooth; I can’t believe I didn’t tie up the dangling loose end of “pretty much is good enough”; I wish I’d gone ahead and attacked the name of “graphic novel,” which is one of the main reasons why we’re all so het up about literature and not so much worried about art. (Aht?) There’s some nice comments over at the Valve, and I hope I wasn’t the last one in the pool. —Mostly I wish I hadn’t utterly missed the obvious joke of Canon and Continuity.