Existing in grids and swerves.

You know that London swings.

New York’s a grid.

Chicago swings.

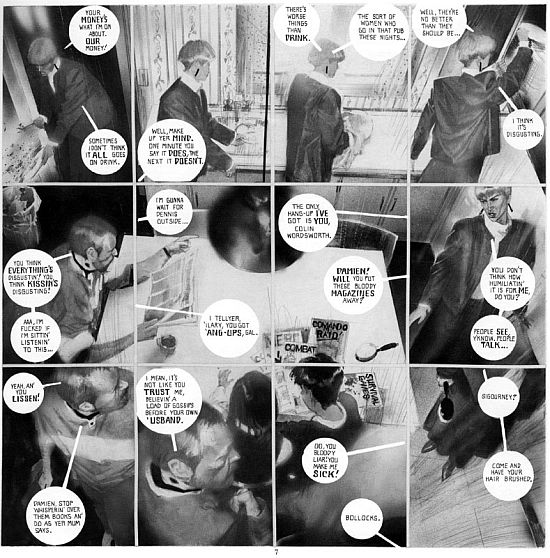

Just about every writer who’s tried their hand at a comicbook script has when describing a scene or a panel to be drawn said something like ZOOM IN or TRACKING SHOT or SMASH CUT. The artist, when they get the script, will roll their eyes heavenward in a silent prayer of not again, before taking up their pen to attempt, once more, to suggest the dynamic motion of cinema with the one-fixed-image-after-another of comics.

(Fun fact: that writer and that artist can easily be the same person.)

It’s jargon creep, is what it is. —“Jargon,” we are told, “is the inevitable outcome of the specialised communicational needs of professionals, who require terms for things and situations which they, as a matter of necessity, have to deal with every day of their lives, but which do not enter into the world of the man on the Clapham omnibus except as occasional ‘technical’ matters,” and that’s all well and good insofar as it goes, but when one’s specialised communicational needs are themselves relatively abstruse, expressed in terms of art only haphazardly taught or even studied, with critical apparati that have only just begun to assemble themselves, well: it’s only natural, to reach for something closer to hand, superficially similar (bright colors! pretty pictures! explosions!) but colossally more popular, more easily reached from the Clapham omnibus, and thus more familiar, more well-known—superficially, at least: an approximation of the tools it’s built to satisfy its own specialised communicational needs, osmotically assimilated from backstage tell-alls and glandhanding chroniclers eager to demonstrate an almost professional grasp of the technicalities, and voila: a tracking shot that zooms in to a smash cut. In comics.

—Which isn’t to say there’s never a point in trying to evoke in pen and ink the cinematic swoop of the one, the celluloid abruption of the other, or that interesting effects couldn’t be gleaned from the attempt, but you need to think about how to do that in comics, and what that will do to your comic, and whether the effect is right for the moment, the scene, the story, and reaching just for the closest jargon to hand isn’t doing that thinking. At best, it’s offloading that thinking to our weary, prayerful artist (see above). —Nor is this some sort of Hulked-out Sapir Whorffery, where because you’ve turned to the jargon of cinema, you can’t think in comics at all; but. But: the trick of unthinkingly reaching for metaphorized jargon is that you just don’t bother to think it. You think you already have.

It is possibly the predominant narrative mode in Western movies, television, comic books, what-have-you. And now I learn (via Warren Ellis (via Gene Ha (who cribs it from Dennis O’Neil who deems it “the best imitation of life possible in a work of fiction”)))—it has a name: The Levitz Paradigm.

Speaking of which. —The Levitz Paradigm (also known as the Levitz Grid, which it isn’t) is not a narrative mode, much less the predominant one of anything West of anywhere, and while it’s a useful tool for (a not inconsiderate number of) television shows and (quite a lot, really, though less than before, of Yankee-style) comicbooks, it’s got nothing at all to do with movies as they are currently practiced and produced, to say nothing of novels, and as for your what-have-you, well. And Denny O’Neill’s remark must be approached in a context of specialised communicational needs that straiten severely the very meanings of “best” and “imitation” and “life” and “possible” and “work of fiction” to make the sense it does: “Basically, the procedure is this,” he tells us:

The writer has two, three, or even four plots going at once. The main plot—call it Plot A—occupies most of the pages and the characters’ energies. The secondary plot—Plot B—functions as a subplot. Plot C and Plot D, if any, are given minimum space and attention—a few panels. As Plot A concludes, Plot B is “promoted”; it becomes Plot A, and Plot C becomes Plot B, and so forth. Thus, there is a constant upward plot progression; each plot develops in interest and complexity as the year’s issues appear.

That’s it: the Levitz Paradigm.

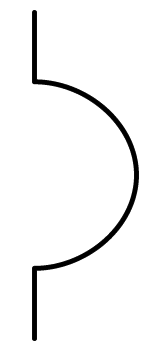

The Levitz Grid (which isn’t a grid) is likewise simple enough: jot your issue numbers or chapter titles or whatever designation you might have in mind for your buckets-of-story along one side of a piece of paper; scribble whatever it is you’re using to keep track of your possible plots (whether I, II, III, or A, B, C, or the One Where Her World Explodes, the One Where He Turns on His Left Side) down the perpendicular, and where each of them meets, make a note: in this episode, this plot will make up the A story (not the A plot—we just crept into sitcom jargon), and this one the B, this one the C, and this one’s taking a smoke break:

But ceci n’est pas un paradigme! The Grid (not a grid!) is just something you use to grasp, manipulate, note and recall the thing itself: the swirlingly fluid interplay of rising and falling actions of ever-churning never-ending storystuff braided in regular packets that nevertheless in their hurly and their burly, their ebb and flow as each crescendoes and recedes in turn to be replaced by the next already swelling, seeming thus to provide an eternally returning imitation of life at least as convincing as their illusion of change: misshapen chaos lent a decently utilitarian but deliberately none-too-well–seeming form. “It’s a fairly simple and useful charting tool for doing serial comics,” says Levitz himself, and there, that’s why it’s got nothing to do with novels, or movies, or short stories, or plays, or much of anything at all that even glances at an Aristotelian unity: this is a tool for comicbookers, soap operators, serialists: θεαμάτων διευθυντές, in the original Greek. —Novels have no need to juggle advancing and retreating plots with an abacus like this; movies-as-such shouldn’t have to twiddle plot-sliders on a giant storystuff equalizer: they’re of a shape, done in one, start to finish: there’s braiding, sure, advancing, retreating, but not on a long-term, continuing basis that requires a grid (that’s not a grid!) to track the paradigm used to keep hold of the writhing swerves of it all.

—Which is not to say you couldn’t, if you so wished, apply serialist tools to a unitary project (yes, you in the back there, a picaresque, of course, now sit down)—but much as when you set out to draw a tracking shot, you need to think a moment, at least, about how, and why, and when. —I’ve never played with the Levitz Paradigm myself, for all that I am a serialist; I can appreciate what it does, and smile to see it at work behind the shapes of comicbooks and television shows, but I don’t keep track of storylines braided in that fashion, which anyway isn’t so much a braid as a splice, or maybe a graft? (Jargon creep…) —However it is I approach the structure of my own storystuff is bound up in a synæsthetic proprioception that I can barely describe and mostly leave alone to do what it does out of fear that I’ll break something by poking at it. The way I feel it in my hands doesn’t translate to abecederial beads strung on an armature of criss-crossing wires: it’s more, I don’t know. Tidal? It does slosh. Sort of. —Anyway.

Not to go on, though, about that post (none of this is to say), a four-year-old recapitulation of an efflorescence of enthusiasm for a simple, careworn charting tool, mostly unspooled in long-since unravelled Google+ threads, which I found because I was looking for another grid, an actual grid, a fabled, magical grid:

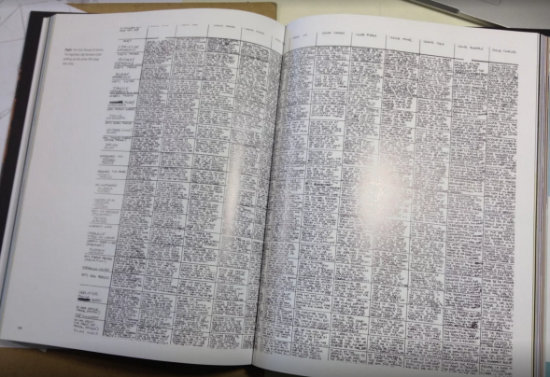

When I started out with this I was living in a state of such terror that I would get to the end of a story and not have an ending for it, or would not have at least a satisfactory ending for it, that I would plot my stories out almost to the finest detail. If I was plotting a 24-page Swamp Thing story I would have a kind of rough idea of where I wanted the story to go in my head, I would have perhaps vague ideas of what would make a good opening scene, a good closing scene, perhaps a few muddy bits in the middle. I’d then write the numbers 1 to 24 down the side of the page and I would put down a one line description of what was happening on that page. This kind of developed to the point of mania with Big Numbers.

When I plotted Big Numbers I plotted the entire projected 12-issue series on one sheet of A1 paper—which was just frightening. A1 is scary—it’s the largest size. I divided it along the top into 12 columns and along the side into something like 48 different rows across which had got the names of all the characters, so the whole thing became a grid where I could tell what each of the characters was doing in each issue. It was all filled with tiny biro writing which looked like the work of a mental patient, it was like migraine made visible, it was really scary.

I mainly did it to frighten other writers—Neil Gaiman nearly shat, the colour drained from his face when he saw this towering work of madness. I’ve still got it somewhere, I just don’t look at it very often, it doesn’t make me feel good, it’s sort of: “Where was I?”

And much to the credit of that post, it offers a glimpse of the beast:

Now: that’s a grid. But it’s not a Levitz Grid. (Which, anyway, isn’t.) It’s got nothing at all to do with the Levitz Paradigm: superficially similar, perhaps (there’s the issue numbers along the top! there’s the characters, written down the side, just like possible plots!), but the plots-as-such aren’t jockeying for position, each taking their run at the top as the previous focus retires; there’s no Story A or B or C, to track and note their relative placements in time. There’s just a grid (just), a map in time, of who needs to have done what by when, to pull it all off. —Big Numbers was episodic, in that it was strictly structured around 40-page issues that had specific beginnings and endings (at least, the three that managed to make it out into the world from the shelves of Kupe’s library)—but it isn’t (wasn’t) a serial. Or at least what was serialized about it wasn’t the start-and-stop of rising and falling repeating and returning stories, per se; I mean of course it’s a serial, any writer as devoted to rhythm and rhyme and structure as Moore, any artist as formally impishly devious as Sienkiewicz, they’re going to rank and arrange elements of their work to unfold in a serial manner, yes, of course, hang the swerves on an unrelenting nine-panel grid just to show how much it isn’t, can’t be, couldn’t, repeat and return to reach for what can’t, and yet—

My specialized communicational needs exceed my grasp. (Where the words do fail.) —Christ, I caught myself just now looking up serialist composition, just to maybe have something to say it with. (Talk about jargon creep.) —I went looking for a Big Damn Example of something I might want to think about using, myself; stumbled over a post that mildly annoyed me with its innocently inaccurate enthusiasm; started to think my way through how, and what, and why, and I’ve ended up in an unlooked-for existential crisis, over what is a serial, and what isn’t, and why I think I feel as strongly as I do about this bit, or that. Or that over there, God damn.

Thus, the problem of argument: one talks oneself onto a branch that ultimately must break. I should maybe get back to the thing-that-argues? (This was all a procrastination from the thing-that-argues.)

Bombay’s a grid.

Delhi swings.

Vincent Adultman by a nose.

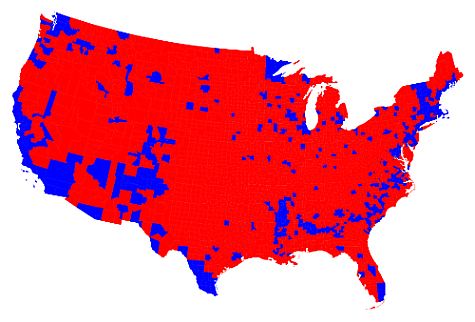

“Bernie Sanders isn’t the frontrunner in the Democratic race. The moderates are” is just a slightly smarter centrist take on “Look at all the red counties on the electoral college map and tell me Trump can’t win!”

January, February, March, April, May, I'm alive

June, July, August, September, October, I'm alive

November, December, you all through the winter,

I'm alive

I'm alive...

Here’s a copy of that calendar of East Portland campsites we noted earlier. (“I think that we are used to having solutions to problems and we’re trained in really specific ways to have really specific solutions to really specific problems,” says firefighter Brett Zimmerman, “and I think when we show up and we don’t have a fix for something and we show up at camps and you can see folks that are struggling right in front of your eyes and you can see folks in hard spaces, and there’s no easy fix in that moment that we’ve been trained to give. That can be heavy and that can be frustrating because we want to help and we want to solve things. And I think that frustration can make you feel pretty helpless, and there’s positive ways to deal with that, and there’s less positive ways. Humor can be both.”)

Which side are you on, folks? Which side are you on?

“Which flavor of authoritarian oligarch would you prefer? The one who is bloodthirsty and vulgar about hating Muslims, or the one who is more polite and technocratic about it? The salivating, rabid racist, or the cool, self-congratulating one? The one who thinks he could get away with shooting someone on 5th Avenue, or the one whose personal “army” actually did after killing Sean Bell at 94th Avenue in Queens? The 73-year old man who measures his dick, or the 78-year old one who thinks the answer is to measure his head? The transgressive, sybaritic daddy who wants you to enjoy all the cheeseburgers you can, or the austere, martinet patriarch who will measure and ration your soda by the calories and ounce? The anal-sadistic pervert who is fixated on how toilets flush, or the anal-retentive one who obsesses over how long employees take to shit? Do you identify more with the retiree who is frustrated with their new, energy efficient appliances, or the still-hard-at-work tycoon who is furious at the inefficiency of his human employees? The lecher who’s fixated on pussy and tits, or the one who prefers mouths and ass?” —Patrick Blanchfield

In much the same way bricks don't.

Let Charles Mudede walk you through a Reddit post about the shuttering of a cinephile palace and how it’s just like what happened at Boeing, and it’s a cliché, I know, to say we don’t make stuff anymore, just money, but nowadays we don’t even do that; we can’t even be bothered to make up the numbers that make the right-colored bar climb in the right direction on a PowerPoint slide. We just make the money stand still in a pool somewhere long enough for a grifter to nip in and slip off with it, and what do you call your act? —The Capitalists!

Scenes from the always-emerging class struggle.

Friends and strangers send me links to Instagram ads, portholes into identically extravagant offices. The waiting rooms are plush mid-century modern, the exam rooms an assortment of delicate monochromes washed in halos of light. There is usually a jungle of plants somewhere in the frame. This week, it was Tend, the dentist’s office that is miraculously also a “studio” and a “dental wellness brand,” where patients brush with Italian Amarelli licorice toothpaste and arrive to find their favorite HBO dramas pre-loaded on a screen. For its expansion it brought in $36 million late last year. A few months ago it was Parsley Health, the functional medicine startup that operates outside the indignities of the insurance system. “Primary care is broken,” according to its founder, and the solution, as rendered by Parsley, is a whole-body approach that includes microbiome and genetics testing. (Supplements, rather than medications, are encouraged but not typically included in the membership fee.)

For those who desire a more overt technological flex in their healthcare journey, there is Forward, another subscription-model primary care doctor where membership grants access to a whole-body biometric scanner and patients view an interactive double of their body during visits. Women have Tia, the members-only gynecologist, or Maven, the virtual prenatal clinic that proudly labels itself “insurance free,” or any of the plush fertility startups Wall Street salivates over as they gaze at market predictions that curve steeply North. At the outer limits, there is the baffling monolith The Well, a private “wellness club” with a dizzying array of offerings within its white-washed walls, including Chinese medicine, energy healing, and $850 consultations with a licensed MD.

Most of these places are trying to replicate, or at least latch on to, the massive success of One Medical, a membership-based primary care franchise that operates nearly 80 locations and went public last week with a valuation of over $1.5 billion, a modest sum given its projected success. Unlike similar startups treating local populations or Medicare patients, One Medical has become the industry’s blueprint, a fantastically valuable company that can also say it is “fixing” healthcare with a straight face. (Scooping up the segment of a $3.5 trillion industry that has decent insurance and extra cash lying around is generally understood to be lucrative as hell.)

There are five signs that foreshadow the death of a god. His body’s inherent brilliance, usually visible from a league or several miles distant, grows dim. His throne, upon which he never before felt weary of sitting, no longer pleases him; he feels uncomfortable and ill at ease. His flower garlands, which before had never faded however much time passed, wither. His garments, which always stayed clean and fresh however long he wore them, get old and filthy and start to smell. His body, which never perspired at all before, starts to sweat. When these five signs of approaching death appear, the god is tormented by the knowledge that he, too, is soon going to die. His divine companions and sweethearts also know what is going to happen to him; they can no longer approach, but throw flowers from a distance and call their good wishes, saying, “When you die and pass on from here, may you be reborn among the humans. May you do good works and be reborn among the gods again.” With that they abandon him. Utterly alone, the dying god is engulfed by sorrow. With his divine eye he looks where he is going to be reborn. If it is in a realm of suffering, thetorments of his fall overwhelm him even before those of his transmigration have ended. As these agonies become twice and then three times as intense, he despairs and is forced to spend seven gods’ days lamenting. Seven days among the gods of the Heaven of the Thirty-three are seven hundred human years. During that time, as he looks back, remembering all the well-being and happiness he has enjoyed and realizing that he is powerless to stay, he experiences the suffering of transmigration; and looking ahead, already tormented by the vision of his future birthplace, he experiences the suffering of his fall. The mental anguish of this double suffering is worse than that of the hells.

Then the tests came quicker and more frequently. One in four jobs had an assessment attached, he estimates. He got emails prompting him to take an online test seconds after he submitted an application, a sure sign no human had reviewed his résumé. Some were repeats of tests he’d already taken.

He found them demeaning. “You’re kind of being a jackass by making me prove, repeatedly, that I can type when I have two writing-heavy advanced degrees,” Johnson said, “and you are not willing to even have someone at your firm look at my résumé to see that.”

Johnson also did phone interviews with an Alexa-like automated system. For one job, he was asked to make a one-sided video “interview” of himself answering a list of company-provided questions into a webcam for hiring managers to view at their convenience. Or maybe an algorithm would scan the video and give him a score based on vocal and facial cues, as more than 100 employers are now doing with software from companies like HireVue.

This central class divide now runs directly through the middle of most parties on the left. Like the Democrats in the US, Labour incorporates both the teachers and the school administrators, both the nurses and their managers. It makes becoming the spokespeople for the revolt of the caring classes extraordinarily difficult.

An especially meritorious contribution to the security or national interests of the United States, world peace, cultural or other significant public or private endeavors.

“There may be some Democrats who think, ‘That’s exactly what we need to do, Rush. Get a gay guy kissing his husband on stage! You ram it down Trump’s throat and beat him in the general election.’ (laughing) Really? Having fun envisioning that.” —Say what you will, but vulgar Freudianism is oftentimes painfully correct. We’ll leave you with the time Letterman spat in Limbaugh’s coffee, for all the good that did the world.

Cæsar’s wife : Trump’s DOJ :: reproach : ?

“He tweeted about it I guess, so people perceived that as him having weighed in.”

In the reign of good Queen Dick.

Speaking of indulging me, I almost forgot to mention—

It’s new book day! Being the almost entirely arbitrary date selected for making the ebook of Vol. 3 of City of Roses available to the general public. (Almost entirely: I didn’t finish the Foreword ’til Monday, so.) —You can buy it from Smashwords, or any of the fine ebook purveyors Smashwords supplies, which maybe might include Amazon, I guess, oh, wait, no, the book has to have sold two thousand dollars’ worth through Smashwords, first. —Ah, I’m not bothering with the Borg so much anymore anyway; it’s not like this is about selling, ha ha, books, so. (If it were, I doubt I would’ve gone with “a wicked concoction of urban pastoral and incantatory fantastic” as my logline, which replaces “gonzo noirish prose,” and I expect you all to update your marketing kits accordingly.)

Or! You could buy them directly from me. I might not respond immediately, but certainly within an hour or three, and I get to keep more of the money, so it’s a win-win insofar as that goes.

Also! Available in Spanish, though not from me. (I think I mentioned these already.)

And there’s always the Patreon. (I don’t have a SoundCloud. That I know of.) —Anyway. Ha ha! New book day!

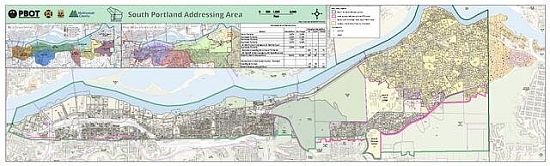

Cartographic spoiler.

If you’ll indulge me a moment:

“Portland,” says Ysabel, spreading marmalade on her toast, “is divided into four fifths.”

“Four,” says Jo. “Not five?”

“Four,” says Ysabel. Leaning over her plate she takes a bite of toast, careful of her sleeveless peach silk top. “There’s Northwest, Southwest, Southeast, and Northeast.” Her finger taps four vague quarters on the purple tabletop between her plate and Jo’s coffee cup.

“What about North?”

“What about it?”

“It’s a whole chunk of town,” says Jo, leaning back. The jukebox under the giant plaster crucifix on the back wall is singing about how you’re all grown up, and you don’t care anymore, and you hate all the people you used to adore. “Isn’t it one of the fifths?”

“There’s no one there.”

“There’s nobody in North Portland.”

“But few of any sort,” says Ysabel, shaking pepper on her omelet, “and none of name.”

“Okay,” says Jo. Stirring her coffee. “But it’s still there. It’s still a part of Portland. It’s still a fifth.”

“If you wish to be finicky, you might also note that there’s no one technically ‘in’ downtown, either,” says Ysabel, cutting a neat triangle from the corner of her omelet. “Or Old Town. So you might speak of six fifths. Or seven. But.” She forks it up, chews, swallows. “I’m trying to keep things simple.”

I always was inordinately happy with that wee early riff on Ireland’s four cóiceda (even if the Shakespeare’s a little on-the-nose). (They’re eating in the Roxy, by the way. I’m serious about being firmly set in Portland.) —So I was anyway initially dismayed to learn that the City of Roses is adding its first new cóiced since 1931:

I mean, “Portland is divided into five sextants” just doesn’t have the same swing, you know? And we’re going to lose the leading zero addresses in inner Southwest, which is one of those charmingly slapdash municipal solutions that seemed brilliant in the moment but now confuse the hell out of underpaid DoorDashers and Amazon delivery drones.

But it’s not like I’m rewriting the riff, and I’m not so concerned with rigorous historical accuracy—I mean, the grand struggle between Good and Evil hinges on whether or not to demolish a ramp that was torn down in 1999. (Oops. Evil wins. Sorry.) —And it’s certainly suggestive, this sudden new neighborhood, carving as it does the Pinabel’s waterfront condominiums and all that other economic development out of the heart of old Southwest. So something’s going to happen in the political situation of my fictional little kingdom—hence the spoiler warning above—only, I’m not yet sure just what that thing will be.

But I have some ideas.

If it be not to come, it will be now. If it be not now, yet it will come—

“The character’s constant preoccupation is action and the lack of it, and as Hamlet comes into his own, Negga shimmers with the thrill of finally doing what has long been talked about. Her enormous eyes, searchlights which seem to see around corners, are suspicious for four and a half acts. But by the end, she’s discovered action, and she beams the good news out to us like a lighthouse finding ships at sea.” —Helen Shaw

You didn’t, Rusty.

“Chip-polt-lay? Say it with one voice. —It’s spelled c-h-i-p-o-t-l-e. Chip-polt-lay, that’s it? You’re telling me it’s Ship-pole-tay? Well, I’m gonna call it Chip-pote-il because I’ve never heard the word pronounced that way, and it doesn’t matter! —Chip-polt-ay? Okay, I’m gonna read the paragraph again ’cause you have distracted everybody now from the point. This is, aw, jeez! This is a piece written by an intellectual, pseudo-intellectual, attempting to explain why Obama was right when he said: ‘You didn’t build that’.” —a recent Medal of Freedom recipient

Aviso de inspección de equipaje.

US Customs and Border Protection destroyed Ballaké Sissoko’s irreplaceable kora on the way out of the country, just because they could, why not. —Somehow, when they told us all the world was getting smaller, I don’t think this was what anyone had in mind. CBP delenda est; TSA delenda est; ICE delenda est; DHS delenda est: delenda, delenda, delenda est, unto the seventh generation.

Apotheodicy.

All I wanted, all I was looking for, was some idea of what the current industry standards are, ratio-wise, height to width, for laying out an ebook page, and I know, I know, the whole dam’ point’s the fluidity and adaptability, there’s no one right true only answer, but there have to be some best practices out there somewhere—a recipe if not for grace, then something that’s more likely than not in most use-cases to end up not ungraceful. (I’d go with the golden ratio, but look at the phone in my hand—design for mobile! we’re exhorted—and you can see the golden ratio no longer so much obtains.)

That’s all I wanted, but it turns out that when you go searching for key words like EBOOK and SCREEN and RATIO you end up skirting a vast, grey-flannel field of rabbitholes lined with websites built from templates to sell you templates you can use to build ebooks with handy preconfigured placeholders into which you merely need to pour your content, crowding out the lorem and the ipsum with your marketing mission statement and your brand story and the repurposed blog posts that will build thought-leadership in alignment with your product direction while addressing the pain points of particular personas to meet the needs of your audience at a given segment of the marketing circle—or is it a sales funnel? a Klein bottle?—all while staking one’s claims to those ever-evolving SEO terms, precious as deuterium. —“Ebook,” you see, is now a term of art in marketing: a genre encompassing works more in-depth and complex than a blog post or presentation, but not so long as a white paper.

It’s one of those uncanny corners of the internet, this field: like a seemingly empty page that shows up in a search result, that turns out to have thousands upon thousands of random words tucked in a hidden div, inadvertently snagging your googling fingers; like those breathless despatches you see in the more financially minded chumboxes, from somebody with a nom de l’argent like The Points Guy, extolling the latest bestest credit cards this fiscal cycle for air miles; like that time I found out I’d been to Maui and attended a luau and written a glowing review, to the tinny approbation of supposedly fellow travelers. There’s a there there, sure—and it’s clean, tastefully lit, properly appointed, apparently well-trafficked, but still and nonetheless: clearly not for the likes of thee and me. —“Haunted” isn’t the right word; one is haunted by the absence of what once was, and this is an imminence of something that isn’t, not yet: that is desperately, hungrily, aspirationally wished-for, hoped-for, right around the corner, just you wait, balls have zero to me to me to me to me to me to me to me to me to an image of the Singularity: the last few ergs from the only Rolls-Royce cold fusion reactor we ever manage to get online juice a sand-pocked, sun-blasted server still somehow running a couple of chatbots locked in zip-squeal conversations, in languages adversarially generated from fulfillment center stocking algorithms, all to game the odds of one of them finally talking the other into joining its proprietary multilevel marketing you i i i i i everything else

I’ve grown disenchanted with disenchantment as a metonym or symptom of the schmerz in our Welt; as the ur-wound dealt us all by the world-storm blowing from paradise. It’s a just-so story, a deeply personal tragedy ideologically smeared over the rest of us, that only seems to explain so much, all out of proportion to its brutal simplicity. —It’s not even wrong: after all, the enlightened triumph of rationalism and positivist thinking sure has left us all a surly, superstitious lot, still grimly bound by all manner of magical thought, and if God is really truly awfully dead, what are all these theocracies clashing over?

It’s a just-so story, a deeply personal tragedy ideologically smeared over the rest of us, that only seems to explain so much, all out of proportion to its brutal simplicity. —It’s not even wrong: after all, the enlightened triumph of rationalism and positivist thinking sure has left us all a surly, superstitious lot, still grimly bound by all manner of magical thought, and if God is really truly awfully dead, what are all these theocracies clashing over?

But the worst of it: by bundling up our sense of wonder, our need for enchantment, our ache for the divine, our zauberung, and telling us we’ve lost it, it’s Ent, we’ve but reified it all into a discretely graspable thing, the lack of which is now more keenly felt; by telling us all that what we want once was, in a storied, demon-haunted past, we make of all our histories a single, othered country: the very fairyland we’ve pretended to disavow. And when you’ve got a bunch of folks aching, seeking, casting about, and you tell them that beyond the fields we know is thataway—

Something hidden. Go and find it. Go and look behind the Ranges—

Something lost behind the Ranges. Lost and waiting for you. Go!

I mean, do you want appropriating colonists? Because that’s how you get appropriating colonists.

So not so much with the disenchantment, no. Now, misenchantment, on the other hand—

In McCarraher’s telling, capitalism as it has taken shape over the past few centuries is not the product of any kind of epochal “disenchantment” of the world (the Reformation, the scientific revolution, what have you). Far less does it represent the triumph of a more “realist” and “pragmatic” understanding of private wealth and civil society. Instead, it is another kind of religion, one whose chief tenets may be more irrational than almost any of the creeds it replaced at the various centers of global culture. It is the coldest and most stupefying of idolatries: a faith that has forsaken the sacral understanding of creation as something charged with God’s grandeur, flowing from the inexhaustible wellsprings of God’s charity, in favor of an entirely opposed order of sacred attachments. Rather than a sane calculation of material possibilities and human motives, it is in fact an enthusiast cult of insatiable consumption allied to a degrading metaphysics of human nature. And it is sustained, like any creed, by doctrines and miracles, mysteries and revelations, devotions and credulities, promises of beatitude and threats of dereliction. McCarraher urges us to stop thinking of the modern age as the godless sequel to the ages of faith, and recognize it instead as a period of the most destructive kind of superstition, one in which acquisition and ambition have become our highest moral aims, consumer goods (the more intrinsically worthless the better) our fetishes, and impossible promises of limitless material felicity our shared eschatology. And so deep is our faith in these things that we are willing to sacrifice the whole of creation in their service. McCarraher, therefore, prefers to speak not of disenchantment, but of “misenchantment”—spiritual captivity to the glamor of an especially squalid god.

That’s a better way, I think, to go massive, sweep it all up, things related and not, and much as with Reagan, it’s hard to go wrong when you’re blaming the Puritans (though not just them alone, God knows). But it’s still not quite right: misenchantment implies there’s a right way to go about it, that we missed; a wrong track or a foot we got off on, and all we have to do is get back on the right one, right? —And having thusly reified it, off we hare after the one right way, that unencumbered enchantment still somewhere out there, instead of looking about here and now, to what might be done to make things better (more enjoyable, more livable, more just) and not, well, worse (less; not; un).

—Malenchantment, maybe?

And, for an instant, she stared directly into those soft blue eyes and knew, with an instinctive mammalian certainty, that the exceedingly rich were no longer even remotely human.

you i i i i i everything else

It’s funny,

but none of the folks who insist that affirmative action degrades both accomplishment and accomplisher seem to mind that Rush “who the hell cares” Limbaugh is only getting a Medal of Freedom to pwn the libs.

Fake news.

So I had this whole riff on how the controversy (?) over how it turns out James Corden’s Range Rover is being towed whenever they film those Carpool Karaokes (!), on how that’s what happens when the news is filled with Republicans pissing on your leg and telling you it’s raining people telling violently bald-faced lies without even caring whether they’re believed, and it’s overwhelming everything that you and everyone you know and love knows to be true, and there’s nothing you can do about it, you can’t call those people out, you can’t touch them, you can’t even spit in their coffee, and changing the channel does no good at all anymore, it’s in the air, it’s on your phone, it covers you now like some sort of film, in your hair, your face, like a glaze, a coating, a patina of shit, I mean, and voting doesn’t do any God damn good, and even if you are a Republican openly affect to agree with them this constant grinding degrading cognitive dissonance is going to take a toll, is going to build up pressure that has to be relieved somewhere, somehow (to get hydraulic for a moment), is going to squirt out at the oddest moment, lashing when it sees a chance to feel weirdly betrayed by a cheaply obvious bit of televisual trickery, I mean, who out there is really all that invested in the belief that actors must really be driving when they’re playing at driving a car? (James Garner as always excepted, of course.) —I had this whole riff, but it turns out it’s really just that James Corden’s actually kinda a dick, and people don’t like him. So.