If the basilisk sees its reflection within 30 ft. of it in bright light, it mistakes itself for a rival and targets itself with its gaze.

Mike Hoye wrote a charming takedown of the implications of and actual use cases for “effective altruism,” soi-so-very-disingenuously-disant, and I call it to your attention for that, but also for his description of the more abstruse theology behind the ideology:

It’s what you’d end up with if you started with Scientology and replaced “thetans” with “dollars.”

I expect you all to be doing your part to immortalize it.

As to that theology: it’s as grubby and grasping as you’d expect, a premillennialism that dispenses with any need to give an inconvenient shit about the here and now in favor of the serenely happy could-be maybes of literally trillions of one-day someday others—an imaginary euphoria so massively vast that a billionth of a percentage point of the chance that it might come to pass outweighs whatever petty sun-dried raisins might float in the head of whomever’s life is spent in the grindingly horrible labor necessary to build the device that calculates it. The whole affair’s suffused with an overwhelming, overweening aroma of three-in-the-morning dorm-room debate, and it took me a moment to realize the déjà I kept vuing as I read along:

Effective altruism is nothing more than Roko’s basilisk.

Oh, some of the rough edges have been smoothed away, some of the bullshit wiped off: we’ve lost the time-travel and the tortured clones and the games of Prisoner’s Dilemma you’re supposedly playing with yourself; we’ve traded a bizarrely psychotic omnipotent future-AI supremely concerned with what we are doing here and now to bring it someday about for a future of trillions of happy intelligences happily skipping about endless holodecks of fun and adventure that can only someday be brought about by what we’re doing here and now—but that’s just the sort of renovation you’d do to weaponize the notion into a nostrum you could sell to tech-addled billionaires. One can’t help but be (disgusted, but) impressed.

I mean, Jiminy flippin’ Cricket: the post in which Roko first introduced the damned thing is titled Solutions to the Altruist’s Burden: the Quantum Billionaire Trick.

—It’s a cold comfort (most of our comforts are chilly, these days), but it’s worth noting that the basilisk is one of the dumber monsters in the D&D bestiary, with an Intelligence of 2. It helps to explain why Zuckerberg’s burning Facebook to the ground for a metaverse nobody wants, here and now: someday, maybe, trillions of legless avatars might blissfully revere his name.

Every billionaire is a policy failure. Every billionaire is a weapon of mass destruction. Every billionaire is history’s greatest monster. Every billionaire is an injury to the world. Every billionaire is an affront to God. Every billionaire must be taxed out of existence.

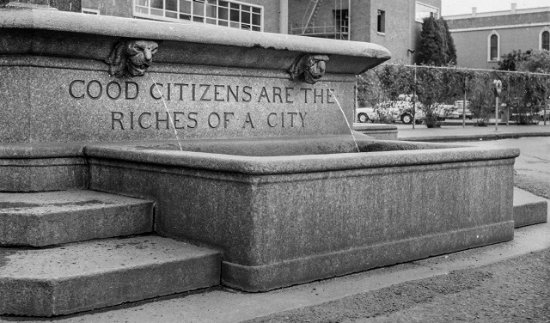

Good citizens are the riches of a city.

That’s what’s engraved at the base of Skidmore Fountain, at the direction of C.E.S. Wood, who had the fountain designed by his good friend Olin Warner, and it’s unclear to me if that’s something he (Wood) was known for having said, and chose to memorialize, or merely an epigram composed for the purpose; it doesn’t so much matter. The saying’s firmly fixed, to him, to the city, to history, to the fountain, to us, so much so that when it came time for me to stage a political debate in the epic, in the storied civic temple of the City Club of Portland, I made sure to build the victor’s rebuttal around that very motto:

(Said fictional debate, and I mention this, I indulge in this detail, because it will turn out to have been somewhat germane, is between the candidates for mayor, the one of them our smoothly corporate cipher, the challenger, who’s not so much based on as representing the place and role in the political firmament of former mayor Sam Adams, and Sam Adams is the label of a once microbrewery gone successfully corporate, and so the challenger’s named Killian, since Killian’s is the label of another microbrewery, ditto; his opponent, the older skool incumbent, rather more directly based on also-former mayor Vera Katz, is, of course, named Beagle, and so.)

—Anyway. So much for the riches of a city.

City Council Passes $27 Million Budget Package to Fund Homeless Encampment Plan

Portland City Council voted 3 – 0 Wednesday morning to approve a controversial budget package that lays the groundwork for a plan to criminalize street camping and build mass encampments to hold unhoused Portlanders by 2024. Both city commissioners Carmen Rubio and Jo Ann Hardesty were absent for the morning’s vote. (According to council staff, Hardesty is on a planned vacation and Rubio is out sick.)

The details of the “mass encampments” the plan speaks of are somewhat in flux: ranging from holding a thousand people each (that version would’ve been maintained by National Guard “security specialists”) to maybe a hundred each, at the start, let’s see; the most generous reading of the plan in its current state would be enough to hold 750 people, total.

The most recent point-in-time count of those experiencing homelessness in the TriMet area? 6,633 people, on the night of January 26, 2022.

I suppose providing some “official” place to camp for ten percent of the people affected counts as just about the equivalent of a Band-aid® in dealing with a homelessness problem?

—Of course, the mass encampments aren’t really there to provide official places to put anyone. The camps are there to provide a fig leaf to allow for the most important provision of the plan: the criminalization of unsanctioned street camping. —In 2019, the Supreme Court declined to hear an appeal of Martin v. Boise, in which the Ninth Circuit found it was a violation of the Eight Amendment to jail, fine, or cite individuals for doing what they could not otherwise avoid doing: if a city does not provide places for those without homes to sleep, it cannot persecute them for sleeping without a home.

But hey, the City of Portland can now say. We’ve got these camps, or will, soon enough. You have legally sanctioned options you’re electing not to exercise; we may now criminalize your behavior. So! GO—MOVE—SHIFT—

This ghastly disaster was yeeted from the public sphere back in February, when it was originally trial-ballooned in a blue-sky memo by none other than said former mayor Sam Adams, now a top aide to our current mayor, Ted Wheeler: “a plan to end the need for unsanctioned camping,” he said, but also, “This is not a proposal, this isn’t even a plan,” and “This is Sam Adams putting concepts out there, looking for discussion.”

“That idea would never fly with us,” said City Commissioner Carmen Rubio at the time, “and if true, I hope that would be a nonstarter for the mayor.” And City Commissioner Jo Ann Hardesty said, “Based on what has been reported, this half-baked plan is a nonstarter.”

Welp, elections have consequences, and so it would appear does a national pre-election campaign of screaming fearmongering as regards CRIME and the need for LAW AND ORDER; that which was roundly shouted down in February is officially if hastily proposed in October and approved, with preliminary funding, by a 3 – 0 vote of our five-member council, in November. “These resolutions do not criminalize homelessness,” insisted City Commissioner Dan Ryan, who, along with Commissioner Mingus Mapps and Mayor Ted Wheeler, voted for the plan, and of course, he’s right; they merely criminalize homelessness anywhere he’d otherwise have to see it.

But that 27 million dollars has to come from somewhere. The budget as approved cuts (among other line items) 8 million dollars from the city’s allotment to the Joint Office of Homeless Services, and threatens to cut another 7 million more. Gutting the JOHS threatens shelters that currently provide a couple-hundred beds and rent-assistance programs that support another fourteen hundred or so people not currently experiencing homelessness.

Oh, well. Guess we’re going to need a bigger mass encampment.

Yes, Portland has an issue with homelessness. Not unlike every other city in the country. Yes, one might even refer to it as chronic. The solution is simplicity itself: you give people homes. An answer so self-evident should not require proof, but it has been proven, over and over again, from Houston to Finland: housing comes first. But our good citizens, or at least the ones currently in office, are criminally stunted in their political imaginations; our riches in that regard are, sadly, depleted. Salt & Straw is threatening to leave downtown, for God’s sake! We must be seen to be doing something. Once it’s swept away, out of sight, and business has returned to what we might remember as having been normal, then we can turn our meagre attentions to the longer term. You’ll see.

But. Until then—

How it started / How it’s going;

or, The ratchet.

You might recall that Andy Ngo, fascist provocateur and inspiration to multiple mass shooters, fancies himself (when he isn’t gleefully ordering the suspension of leftist accounts on Twitter) as something of a journalist: why, he’s even written himself a book! —Here’s how Powell’s wrote it up in their online catalog just a couple short years ago, when it was first released:

Unmasked by Andy Ngo came to us through an automatic data feed via one of our long-term and respected publishers, Hachette Book Group. We list the majority of their catalogue automatically, as do many other independent and larger retailers. We have a similar arrangement with other publishers.

This book will not be on our store shelves, and we will not promote it. That said, it will remain in our online catalogue. We carry books that we find anywhere from simply distasteful or badly written, to execrable, as well as those that we treasure. We believe it is the work of bookselling to do so.

And, well, here’s how Powell’s now writes up the revised edition, with its brand new afterword from the author:

In this #1 national bestseller, a journalist who’s been attacked by Antifa writes a deeply researched and reported account of the group’s history and tactics.

When Andy Ngo was attacked in the streets by Antifa in the summer of 2019, most people assumed it was an isolated incident. But those who’d been following Ngo’s reporting in outlets like the New York Post and Quillette knew that the attack was only the latest in a long line of crimes perpetrated by Antifa.

In Unmasked, Andy Ngo tells the story of this violent extremist movement from the very beginning. He includes interviews with former followers of the group, people who’ve been attacked by them, and incorporates stories from his own life. This book contains a trove of documents obtained by the author, published for the first time ever.

In conclusion, fuck Powell’s.

Meanwhile, in fascist Twitter.

The reason they’re going so openly, distressingly hard (beyond what savagely infantile joy there is to be taken in the mere fact that they can) is because they are shook: they have come just this close to losing an ounce of ill-gotten privilege, and that fact alone has their mouths parched and their palms clammy and their guts in knots, their instincts rattled to the point they forget the thing to do in polite company is to hide who they truly are. They are terrified. —It’s a mean, cold comfort, perhaps, but take what of it you might; we have a long and ugly fight ahead.

GO—MOVE—SHIFT

Telling as all get-the-fuck-out that in the headline “Portland neighbors beg for help as homeless camp takes root” the NEIGHBORS doing the BEGGING aren’t the ones without a roof.

Pontypool variations.

All due respect to Barry, the cartoonist, but his analysis I think leaves out a wide middle swath: there are Republicans, who are tools, who believe ridiculous lies; there are Republicans, who believe in the power of ridiculous lies; and then there are Republicans, who know, deep down, the lie isn’t true, but pretend to believe with all their heart, no matter how ridiculous, because it gives them the excuse they need to do what they want to do anyway. It’s this last set that are the most dangerous, but also our only hope: if the cost of pretending to believe the lie’s too great, they’ll stop—because they can. —It’s just the cost is so damn cheap these days, is the thing.

Smothered.

Why on earth would anyone watch the nightly fascist divagations of Tucker Swanson McNear Carlson? —It’s not just the monotonously sour, pinch-faced homiletics of a Haw-Haw aspirant desperately trying to keep up with the Facebooked racism of his lessors, but also, apparently, every commercial break you’re gonna have to sit through a couple-three spots for those slipperily awful pillows, over and over and over and over again. Who does that to themselves?

Abaugurate.

“When I left there Wednesday, I was real happy and proud of our team,” said Kevin Grooms, who works in the Paint Shop. The white paint on the inaugural stands was completely finished, and they had made it through nearly three-quarters of the blue detail work. “We worked until probably twelve o’clock Wednesday. And the blue paint that was on the deck was actually still wet.”

“We came back on Thursday morning, and I mean, it was completely destroyed,” he said. “It was just totally demolished. The blue wet paint, they tracked it all over.”

There was also trash and debris covering the stands. “Besides the stands having a lot of debris on them, there was a lot of broken glass. And there was a significant amount of residue from the tear gas. It was very difficult cleaning up that area,” said Serock, who noted that the US Capitol Police provided important guidance on how to safely handle these items.

“It was a real mess, it was unbelievable. You just can’t imagine,” said Grooms. “We’re still in shock over it.” But his team worked through the weekend, “When I left there Sunday afternoon, that deck looked like it did Wednesday. Now, it’s pretty much down to touch-ups.”

—via the staff of the Architect of the Capitol

Early yesterday morning, a knot of curious spectators stood on a corner of Connecticut Avenue, craning their necks over a procession of black SUVs and police cars to try to catch a glimpse of Biden. I asked one of the DC reporters standing there if she knew the best path through the cordon of checkpoints surrounding downtown. She glanced down at my unadorned neck and then said, in the manner that you would speak to the Official Rube Correspondent of the Hicksville Gazette, “Um, I think you need a credential to get down there.”

Because I try to avoid wearing press credentials out of both a philosophical belief that the experience of a journalist should mirror that of the general public and the fact that I often work at publications not considered fancy enough to be approved for press credentials, I was determined to navigate DC as any other citizen. It was true that you needed a credential to get anywhere close to the Capitol or even the National Mall, where you might be able to see or hear the actual ceremony. The series of scary-looking metal fences and concrete barriers that began all the way up at K Street, though, could be passed through, although the United States government did not seem to want anyone to be aware of that fact.

At every opening in the security fence, there stood a line of soldiers, with M‑16s, surrounded by a motley assortment of Secret Service and metro cops and FBI agents and Park Police. Concrete slabs were erected to funnel you down this imposing gauntlet of the security state. There was not a single sign saying, for example, “This Way to Inauguration,” or “Entrance Here,” or “Public Access,” or anything else. There was only the military checkpoint, the armed men in sunglasses, and the mostly empty streets. Even I, a basic white man, had to gather a fair amount of courage to approach the stone-faced soldier behind the nearest metal fence and ask if there was a way to get through.

“Oh yeah, you can walk right in here,” he said, gesturing to the terrifying prison-esque checkpoint. “These are open.”

The greatest trick the devil ever pulled

was convincing Democrats that “political capital” is a fungible, depletable resource.

A frozen peach of Serendip.

In searching for something more from William Empson on Edmund Spenser, I happened upon a listing for Radical Spenser, which, I mean, you know, okay, I’m in, but I didn’t want to give Bezos any more money, so I went poking about the Powell’s catalog, and as it turns out they don’t have it at all (recently cutting bonds with the river might maybe have something to do with it; that’s me, always with the edge cases), but: but. —There, between Cold Service Spenser [sic] and Jane Mayer’s Dark Money was, well, this striking bit of in-house marketing copy:

At Powell’s, a lot of our inventory is hand-selected, and hand-promoted. And a lot of our inventory is not. With several million titles available online at any given moment, complete hand-curation is not possible. Unmasked by Andy Ngo came to us through an automatic data feed via one of our long-term and respected publishers, Hachette Book Group. We list the majority of their catalogue automatically, as do many other independent and larger retailers. We have a similar arrangement with other publishers.

This book will not be on our store shelves, and we will not promote it. That said, it will remain in our online catalogue. We carry books that we find anywhere from simply distasteful or badly written, to execrable, as well as those that we treasure. We believe it is the work of bookselling to do so.

And this is how it works, in an interconnected age: when one orders books from let’s say Powell’s, one does not order a book Powell’s currently has on their shelves, or stacked on pallets in their warehouse; just-in-time inventory management allows Powell’s to take your order, pass it along to a distributor, receive from them a copy of the book you want, and pass it back to you, taking a slice along the way, and all so quick you’re usually none the wiser. (Trust me: I’d know if Powell’s actually had 20 copies of one of my books a-waitin’ in a warehouse.) —The downside, of course, is the very lack of those hands, selecting, promoting, curating, which also funnily enough is why YouTube’s such a cesspool, and Twitter a hellsite, and Facebook the destroyer of all we might hold dear. Such a common tragedy.

It should also be noted that said long-term and respected publisher, Hachette Book Group, one of what used to be the Big Five (not counting Bezos), launders its profits through various imprints, so that the money from the street doesn’t get its stink on their name—unless someone like Powell’s goes and gives up the game, most folks would just see that milkshake boy’s first book was published by Center Street, home to such other distinguished authors as Jeanine Pirro, Newt Gingrich, and Donald Trump, Jr. —Undoubtedly, much like those distinguished others, this doxxing grifter will likewise benefit from the conservative book club bulk buy two-step—so, hey, congratulations?

Still: you’d think such cut-outs would make it easier, not harder, for an incomplete hand to still curate its inventory by saying no, not those, not the ones with that label. There being so many, and so carefully calibrated and all. —Funny, that.

All Cops Are Bigoted/Bootlicking/Bastards.

Portland police have used force—in the form of rubber bullets, baton strikes, tear gas volleys, and other acts—more than 6,000 times against Portlanders protesting police violence and racism this year.

This information comes from two newly-updated reports from the Portland Police Bureau (PPB), documenting officer use of force data for the second and third quarters of 2020, a period spanning April 1 and September 30. On Friday, the Mercury shared data from the second quarter report, which found that, in the first 32 days of Portland’s protests—which began on May 29—PPB officers used force against protesters 2,378 times. The release of the third quarter’s data offers a more comprehensive look at the damage inflicted on Portlanders by police this year through what PPB calls “crowd control.” Combined, PPB used force at least 6,249 times against members of the public during 2020’s second and third quarters.

The PPB reports note that this number is likely an underestimation, as some officers did not record every time they used force on a protester.

In comparison, PPB used force against protesters 64 times in 2019, 205 times in 2018, and 162 times in 2017.

I spoke with Jake Angeli, the QAnon guy who got inside the Senate chamber. He said police eventually gave up trying to stop him and other Trump supporters, and let them in. After a while, he said police politely asked him to leave and let him go without arrest.

Like tears in rain.

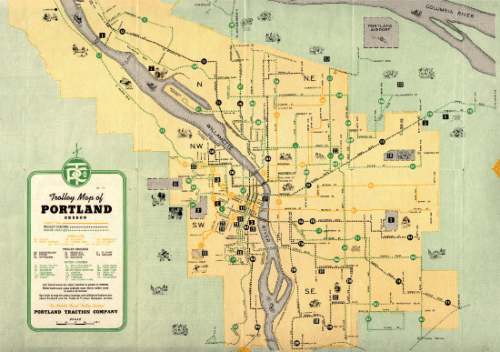

I miss restaurants, sure, of course, but there’s take-out, which salves at least the most immediate loss (to me, of course.) —You know what I really miss? Busses. I got so much reading done on the bus.

—in the palaces of Kings, in the drawing-rooms and boudoirs of certain cities—

Even if these problems could be overcome, other barriers to integration would likely present themselves. Keystone transsexual activists are of generally of [sic] lower socio-economic status, and are probably reliant on their private dwellings for offline meeting. Additionally, while keystone radical feminists generally have homes with reception rooms, transsexual dwellings are probably much smaller (likely amounting to a studio flat or a single bedroom in shared accommodation) making the level of social familiarity required to be invited in unusually high. It is also possible that the private behaviour of transsexuals is so abnormal and morally depraved as to rule out accepting such an invitation [sic sic sic].

As such, no “inner sanctum” discussion has ever been observed, either online or offline. Likewise, no operative has succeeded in forming any form of friendship (let alone an intimate relationship) with a transsexual activist.

This time she went ahead of him and opened a door she felt must be to the kitchen. Light fell on desolation. Worse, danger: she was looking at electric cables ripped out of the wall and dangling, raw-ended. The cooker was pulled out and lying on the floor. The broken windows had admitted rain water which lay in puddles everywhere. There was a dead bird on the floor. It stank. Alice began to cry. It was from pure rage. “The bastards,” she cursed. “The filthy stinking fascist bastards.”

They already knew that the Council, to prevent squatters, had sent in the workmen to make the place uninhabitable. “They didn’t even make those wires safe. They didn’t even…” Suddenly alive with energy, she whirled about opening doors. Two lavatories on this floor, the bowls filed with cement.

She cursed steadily, the tears streaming. “The filthy shitty swine, the shitty fucking fascist swine…” She was full of the energy of hate. Incredulous with it, for she had never been able to believe, in some corner of her, that anybody, particularly not a member of the working class, could obey an order to destroy a house. In that corner of her brain that was perpetually incredulous began the monologue that Jasper never heard for he would not have authorized it: But they are people, people did this. To stop other people from living. I don’t believe it. Who can they be? What can they be like? I’ve never met anyone who could. Why, it must be people like Len and Bob and Bill, friends. They did it. They came in and filled the lavatory bowls with cement and ripped out all the cables and blocked up the gas.

Infiltration into large affinity group meetings is relatively simple. However, infiltration into radical revolutionary “cells” is not. The very nature of the movement’s suspicion and operational security enhancements makes infiltration difficult and time consuming. Few agencies are able to commit to operations that require years of up-front work just getting into a “cell” especially given shrinking budgets and increased demands for attention to other issues. Infiltration is made more difficult by the communal nature of the lifestyle (under constant observation and scrutiny) and the extensive knowledge held by many anarchists, which require a considerable amount of study and time to acquire. Other strategies for infiltration have been explored, but so far have not been successful. Discussion of these theories in an open paper is not advisable.

Don dances in the wet street.

Grad School Vonnegut got to Timequake, and of course to Trout’s Credo:

You were ill,

but now you’re well again,

and there’s work to do.

But—and I’m not nearly fluent enough in British fashion or football hooliganism or recent trends in international capital to unpack everything that’s going on in this ad; still—

You are as you have been,

but the world will never be again—

and yet, there’s dancing to be done.

I’m reminded of something I wish I could find, that Geoff Ryman said about his novel, The Child Garden, but it was some time ago, and I can’t remember the words; still, the gist of it was that dystopias are usually limited because they presuppose a here-and-now: as cautionary tales, they’re presented as problems for their protagonists to solve, worlds to be saved, not lived in, and how exhausting is that? How much better would it not be to write to draw to film to record a story about just living in the world as whatever it is it might be?

I know, I know: saving is what misers do. But I don’t know.

If it doesn’t happen, what we’ll see is a variety of predictable partial responses: unevenly distributed technological innovation, and cultural forms of quietism and accommodation. If we can’t really do anything collectively, people will try to live with disaster, internalizing and riding it rather than trying to change it.

Failsons & November criminals.

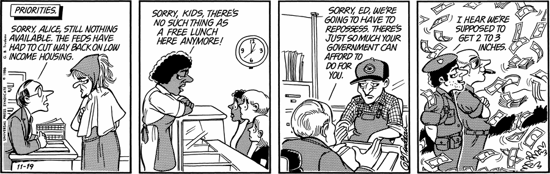

O frabjous day! Callooh! Callay! It’s the thirty-fourth anniversary of my radicalization, which I can date with such alacritous precision due quite simply to the fact that it in turn is due to a comicstrip:

It was more of a straw and a camel’s back than a short sharp apocalypse: and it’s not like there wasn’t then or isn’t even yet a long ways left to go (not too much later, I found myself at Oberlin, tut-tutting my fellow students’ embrace of John Brown, whom I, ’Bama boy that I am, took, at the time, to be a righteous but nonetheless terrorist)—but, but: I’d wet my feet in a Rubicon. We could’ve been making the world a better place. We chose not to.

Thinking about how much of what was then recent history I learned back in the day not from lectures and classwork, from school, but from nipping off to the library to dig through Doonesbury collections, augmented by archives of Feiffer and Herblock and, well, yes, MacNelly, one must have balance, one supposes.

Thinking about that because of what Pat Blanchfield says in this snarkily “Bruckheimer shit” walkthrough of the latest instantiation of the (wildly popular) (wildly deranged) Call of Duty franchise—

A quarter of a billion people, whatever, have played these games, um, and so many American men do, one of the few ways a lot of people ever learn anything even resembling, like, the existence of this history, like, for example, like, in the last game, we were in Angola, is through these games.

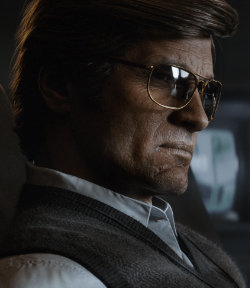

Sobering, and not just for the ideology the games are steeped in, Dolchstoßlegending this or that regrettably unpleasant incident from Yankee history into thrillingly deniable covert ops that left the world, our world, far better off than it otherwise could’ve been, and don’t you forget it— not just the ideology, but also the technique: the hilariously toxic masculinity (when have you ever seen Robert Redford looking so ghoulishly rugged?), the conversational hooks and moral dilemmas drawn from grade-Z B-movie scripts (to say nothing of those meticulously recreated backlot backdrops), all the eye-snagging tics and dialects of body language drawn from deeply uncanny valleys, and touches like the robustly verbose commanding presence of President Dutch, who marches into an expository cutscene (after a prologuizing Gladio massacre) ahead of an anachronistic shaky cam—this isn’t the Reagan to be found in anything close to any actual history this world came up out of; this is a Reagan from a Saturday Night Live skit—

not just the ideology, but also the technique: the hilariously toxic masculinity (when have you ever seen Robert Redford looking so ghoulishly rugged?), the conversational hooks and moral dilemmas drawn from grade-Z B-movie scripts (to say nothing of those meticulously recreated backlot backdrops), all the eye-snagging tics and dialects of body language drawn from deeply uncanny valleys, and touches like the robustly verbose commanding presence of President Dutch, who marches into an expository cutscene (after a prologuizing Gladio massacre) ahead of an anachronistic shaky cam—this isn’t the Reagan to be found in anything close to any actual history this world came up out of; this is a Reagan from a Saturday Night Live skit—

—(and also, yes, all the guns and the shooting and the extreme violence and all that stuff). —It’s, and I use the term advisedly, a cartoon: both in the sense that it’s deliberately, expressively, ruthlessly simplified, drawing power from its crudely broad strokes, and also in that it’s deliberately, ostensibly disposable: a work of paraliterature no one could ever take seriously, c’mon, a staggeringly elaborate, kayfabily po-faced act of kidding-on-the-square, a deniable covert op that leaves us thinking all unawares with precisely what it is we’ve been laughing at, for however long we’ve been twiddling our thumbs at the flatscreen.

Anyway. Down with all Commander Less-Than-Zeroes, wherever they might be found. Give me a November criminal any goddamn day.

When the operation of the machine becomes so odious.

“Everything that is happening to the men who knew Taylor is happening because prosecutors do not want to hold Taylor’s murderers accountable. This is what the system does when it does not want to secure a conviction. Prosecutors themselves try to poison the jury pool against their own case, creating avenues of doubt before any trial process gets going. They try to impugn the character of people who will have to be witnesses for the prosecution. They try to avoid doing forensic research so that they have no ‘hard’ evidence to present to the jury, should it come to that. And they try, desperately, to get anybody to speak out against the victim so the defense can use those statements against the prosecution at trial.” —Elie Mystal

Our Americans.

“The police officers stepped out of the room for just a brief moment, just outside the door. And I told the physician like, ‘Hey, I work here, I’m a nurse here.’ And that shifted everything.” —OHSU nurse and volunteer medic Tyler Cox.