Put down the poker and nobody gets hurt.

I confess that, in these days of blogroll amnesty, I worry how much longer I’ll be able to claim a spot on the rolls of both the Valve and the Weblog. (Have neither of them noticed how far behind I’ve fallen in the reading? Even the title’s secondhand!) —Ah, well. I can just go cue up “Sailing Day” again, and if that doesn’t do the trick, there’s always another fight elsewhere.

Tipping their hand.

Red is the boldest of all colors. It stands for charity and martyrdom, hell, love, youth, fervor, boasting, sin, and atonement. It is the most popular color, particularly with women. It is the first color of the newly born and the last seen on the deathbed. It is the color for sulfur in alchemy, strength in the Kabbalah, and the Hebrew color of God. Mohammed swore oaths by the “redness of the sky at sunset.” It symbolizes day to the American Indian, East to the Chippewa, the direction West in Tibet, and Mars ruling Aries and Scorpio in the early zodiac. It is the color of Christmas, blood, Irish setters, meat, exit signs, Saint John, Tabasco sauce, rubies, old theater seats and carpets, road flares, zeal, London buses, hot anvils (red in metals is represented by iron, the metal of war), strawberry blondes, fezes, the apocalyptic dragon, cheap whiskey, Virginia creepers, valentines, boxing gloves, the horses of Zechariah, a glowing fire, spots on the planet Jupiter, paprika, bridal torches, a child’s rubber ball, chorizo, birthmarks, and the cardinals of the Roman Catholic Church. It is, nevertheless, for all its vividness, a color of great ambivalence.

—Alexander Theroux, The Primary Colors

Red state, blue state: it’s divisive bullshit, an accident of history barely six years old, it’s a goddamn eyeworm, an honest-to-god meme that won’t get out of the way, a map that warps the thing it maps. It’s magic, is what it is. All this business, George Lakoff and his frames, George Bush and his backdrops, David Brooks capitalizing random nouns in a desperate attempt to bottle that Bobo lighting once more, the hoarse, fierce shadowboxing around “surge” or “escalation” that would be grotesque if it weren’t already so weirdly disconnected—it’s all magic, groping for the emblem or rite, the utterance or name that will when written or shown or repeated often enough bring about that change in accordance with will. Some of it works, some of it doesn’t; as usual, it’s the stuff nobody’s trying to make work that works the best. Psycohistory’s still an art, not a science. (Hence: magic.)

—Digby points us to the latest effort of some apprentices to the art: Applebee’s America: How Successful Political, Business and Religious Leaders Connect with the New American Community. Written by a former Clinton strategist, a former Bush strategist, and a former national political writer with the AP, it purports to tell us:

Political commentators insist that the nation is a collection of “red states” (Republican) and “blue states” (Democrat). The reality is that America is a collection of tribes—communities of people who run in similar lifestyle circles irrespective of state, county, and precinct lines.

And there’s some stuff about Navigators (“otherwise average Americans help their family, friends, neighbors, and coworkers negotiate the swift currents of change in twenty-first-century America”) and how fundamental political decisions are made with the gut and not the head and how the authors have cracked the twenty-first century code with their “LifeTargeting” [sic] strategies, etc. etc. —But at least they’ve abandoned red-state blue-state, right? Faceted their analysis into tribes? Brought some nuance into the picture, beyond those two drastically simplified tribes, red and blue?

Yup. There’s three.

Red. Blue. And Tippers.

No. Not otherwise entertaining Second Ladies with an inexplicable mad-on against explicit pop music. People who, like, tip, from red to blue. And back. Get it? Tippers?

—If you’re curious as to how you’d rate in this 2004-level political analysis, there’s a quiz. I scored as a member of the Red tribe. (Apparently, Dr. Pepper, Audis, TV Guide, and bourbon are all more Red than Sprite, Saabs, US News & World Report, and gin.) —I’m thinking their “LifeTargeting” maybe needs to go back to the drawing board for a bit.

Now, I’m not knocking dualism. Dualism isn’t always bad; like any tool, sometimes it’s useful, sometimes it isn’t. With a book like Applebee’s America, there are, indeed, two tribes: those the authors (and the publisher) are trying to reach, and those they couldn’t care less about. A quick scan of the website makes it clear who’s us and who’s them in this particular case:

Their book takes you inside the reelection campaigns of Bush and Clinton, behind the scenes of hyper-successful megachurches, and into the boardrooms of corporations such as Applebee’s International, the world’s largest casual dining restaurant chain. You’ll also see America through the anxious eyes of ordinary people, buffeted by change and struggling to maintain control of their lives.

This isn’t political or sociological analysis. It isn’t even pop sociology. It’s an I’ve Got Some Cheese book. “Applebee’s America cracks the twenty-first century code for political, business, and religious leaders struggling to keep pace with the times,” says so right on the website. —And if you see yourself as a political, business, or religious leader in this twenty-first century, looking out on the ordinary people from behind the scenes in the boardrooms, well, they’ll gladly hand you a neatly bound stack of printed paper in exchange for your money.

—Nor am I knocking the idea of tribes, or guts. Psychology Today has a mildly interesting follow-up to the “Crazy Conservative” study of mumblety-mumble spin-cycles ago, and really, the basic idea that conservatism stems from fear and uncertainty, that liberalism and tolerance are best nurtured by stability and confidence, these are hardly controversial ideas, when you stop and think about it. (In the terms I’ve chosen, yes. Hush.) —For those who want something boiled a wee bit harder, there’s the work of Mark Landau and Sheldon Solomon, on page 3, which gets interesting about here:

As a follow-up, Solomon primed one group of subjects to think about death, a state of mind called “mortality salience.” A second group was primed to think about 9/11. And a third was induced to think about pain—something unpleasant but non-deadly. When people were in a benign state of mind, they tended to oppose Bush and his policies in Iraq. But after thinking about either death or 9/11, they tended to favor him. Such findings were further corroborated by Cornell sociologist Robert Willer, who found that whenever the color-coded terror alert level was raised, support for Bush increased significantly, not only on domestic security but also in unrelated domains, such as the economy.

Old hat, yes, to anyone who’s been paying any attention at all, but how many of us really do? —You have to turn to page 5 for the punchline.

If we are so suggestible that thoughts of death make us uncomfortable defaming the American flag and cause us to sit farther away from foreigners, is there any way we can overcome our easily manipulated fears and become the informed and rational thinkers democracy demands?

To test this, Solomon and his colleagues prompted two groups to think about death and then give opinions about a pro-American author and an anti-American one. As expected, the group that thought about death was more pro-American than the other. But the second time, one group was asked to make gut-level decisions about the two authors, while the other group was asked to consider carefully and be as rational as possible. The results were astonishing. In the rational group, the effects of mortality salience were entirely eliminated. Asking people to be rational was enough to neutralize the effects of reminders of death. Preliminary research shows that reminding people that as human beings, the things we have in common eclipse our differences—what psychologists call a “common humanity prime”—has the same effect.

Ask us to consider carefully. Remind us of the things we have in common. It’s apparently that simple. Which doesn’t mean it’s easy. And any book that was actually about how to lead and build and make the most would talk about how to do that, and how to keep on doing that.

Anything else is magic, and as any real magician will tell you, magic’s a great way to make some money—but it’s a lousy way to chop wood and carry water.

Blue is a mysterious color, hue of illness and nobility, the rarest color in nature. It is the color of ambiguous depth, of the heavens and of the abyss at once; blue is the color of the shadow side, the tint of the marvelous and the inexplicable, of desire, of knowledge, of the blue movie, of blue talk, of raw meat and rare steak, of melancholy and the unexpected (once in a blue moon, out of the blue). It is the color of anode plates, royalty at Rome, smoke, distant hills, postmarks, Georgian silver, thin milk, and hardened steel; of veins seen through skin and notices of dismissal in the American railroad business. Brimstone burns blue, and a blue candle flame is said to indicate the presence of ghosts. The blue-black sky of Vincent van Gogh’s 1890 Crows Flying over a Cornfield seems to express the painter’s doom. But, according to Grace Mirabella, editor of Mirabella, a blue cover used on a magazine always guarantees increased sales at the newsstand. “It is America’s favorite color,” she says.

—Alexander Theroux, The Primary Colors

After the late, great unpleasantness.

I am a Southerner, for all that I’m expatriate—born in Alabama, raised in Virginia and the Carolinas and Kentucky, I graduated high school in John Hughes land and attended a famously liberal arts college on the North Coast of Ohio. Since then, I’ve lived my life in New York and Boston and the Pioneer Valley and Portland, Oregon, and I haven’t spent more than two weeks at a stretch south of the Mason Dixon. (And those stretches are sometimes awfully few and far between.) —But I cook up hoppin’ john for New Year’s, every year (though, apostasic, I make it without the fatback). I taught my Jersey girl how to eat grits and I make my biscuits from scratch. (Food? Don’t laugh. Look to the roots of your own tongue.) —I’m haunted by the smell of magnolia blossoms, plucked and left in a drinking glass on the mantelpiece. (They smell lemony, the same way apples do.) Long pine needles crushed underfoot, dry, not wet and silvery grey; evergreens burnt brown by the sun. I always forget until I see it from the window of the plane, how red the dirt is, scraped up, laid shockingly bare in circles of development scars that will always ring Charlotte: how wrong it looks, how raw. It’s not the color the earth is supposed to be. It’s alien; I’m home.

For a couple of weeks, at most. And then.

(“You will find no other place, no other shores,” says C.P. Cavafy. “This city will possess you, and you’ll wander the same streets. In these same neighborhoods you’ll grow old; in these same houses you’ll turn grey.”)

—If you aren’t Southern, I don’t know that I can explain the little thrill I felt when I saw the motto for the Levine Museum of the New South: “Telling the story—1865 to tomorrow.” Shock is hardly the word. Frisson even seems too strong. It’s a stifled giggle; a flash of a grin, at something you’d’ve done yourself, but never would have thought to do. It hardly seems worth mentioning, but—well, maybe the About Us page will bring it into focus for the Yankees among us?

What is the New South?

The New South means people, places and a period of time — from 1865 to today. Levine Museum of the New South is an interactive history museum that provides the nation with the most comprehensive interpretation of post-Civil War southern society featuring men, women and children, black and white, rich and poor, long-time residents and newcomers who have shaped the South since the Civil War.

New South Quick Facts

- A Time—The New South is the period of time from 1865, following the Civil War, to the present.

- A Place—The New South includes areas of the Southeast U.S. that began to grow and flourish after 1865.

- An Idea—The New South represents new ways of thinking about economic, political and cultural life in the South.

- Reinvention—The New South encompasses the spirit of re-invention. The end of slavery forced the South to reinvent its economy and society.

- People—The New South continuously reinvents itself as newcomers, natives, immigrants, visitors and residents change the composition and direction of the region.

To say that you are about the South, but dismiss the antebellum—not to forget, because who can forget, not even to repudiate it, but to wave it off as no longer important to the South you want to look at, here and now— Don’t throw out the cotton and the rice, the pastel dresses and grey uniforms, the stars and bars and whips and chains. Those things are all still very much alive and kicking. But cut out the thing that props them up, the hollow rites, the archly wounded pride; blithely (if a little self-consciously) announce you’re leaving the Civil War well enough alone, to all the many other hands that want it; you will turn your attention to everything else, and watch it all fall into some saner perspective—1865 to tomorrow—

(“How long can I let my mind moulder in this place?” says C.P. Cavafy. “Wherever I turn, wherever I happen to look, I see the black ruins of my life, here, where I’ve spent so many years, wasted them, destroyed them totally.”)

The Levine Museum of the New South is currently hosting an exhibit called “Families of Abraham.” Eight photographers spent over a year with 11 families in the Charlotte area—Christian families, Jewish families, Muslim families—recording their holidays and everydays, putting the photos together to demonstrate that when you set aside the different words we’ve each plucked from the same shambolic Book and just look at the people, going about their lives, well, under the chadors and yarmulkes and double-knit blazers we’re all, y’know, the same. Basically.

Which is why, given the way things currently are, what with the Pragers and the Goodes and the Qutbs, this show is important. —But it’s not why it’s important to me.

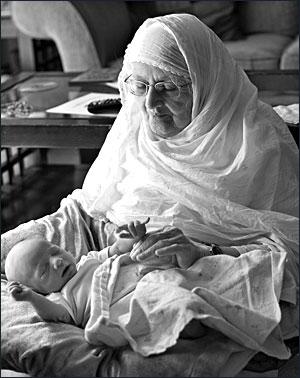

That’s a photo (by my mother, which is why the show is important to me, yes, but), a photo of Basheer Khatoon with her great-grandson, Raahil, taken in the home she shares with her son, a Charlotte cardiologist.

My South—the South in my head, the South I came from—doesn’t have a Basheer Khatoon. But there she indisputably is. Alien—and yet, from all the years I’ve spent since and elsewhere, heimlich. The world has come to the South; the South—my South—is becoming part of the world.

No matter where we go, there we are; we find no other place, no other shore. We wander the same streets, grow old in the same neighborhoods. —But those streets change.

“Vengeance is mine; I will repay,” saith the Lord.

In some otherwise excellent comments on the clusterfucked execution of Saddam Hussein, Josh Marshall said something that gave me pause:

Vengeance isn’t justice. Vengeance is part of justice. But only a part.

I agree that when you’ve been wronged, it can be very, very hard to separate your need for justice from your need for vengeance. This is why judges should always and forever bend toward the asymptote of impartiality, and why “victims’ rights” drives are rarely a good idea.

Vengeance has no place in justice. Vengeance is temporary, short-sighted; the destructive flailing of the hurt who can’t see what they’re hitting. Justice is what you eventually build if you’re lucky enough to survive the ravages of vengeance. —You may feel I’m splitting a miniscule mote plucked from his eye, but this is important: a system of justice that gives any consideration to vengeance is a shameful system, one that mistakes means for ends, that sacrifices peace, justice, for the visceral satisfaction of righteous outrage. Righteous, perhaps; but outrageous nonetheless.

I mean, I know in my bones that impeachment isn’t enough for the various members of the Bush administration. Imprisonment will not bring back the hundreds of thousands of lives we’ve sacrificed for his petty vanity. —When he is turned out of office, I’d want him to tour the country, town by town, set up each morning in the square before the courthouse and allow passersby to sock him in the nose. Not quite inviting passersby to saw at the most famous neck in the realm—Secret Service agents could keep things from getting out of hand—but it would, perhaps, eventually add up in small dollops of vengeance to something you could measure on the awful balance sheet.

But the hundreds of thousands would still be dead, and our nation no closer to something we could claim was health, and the lines would become too long and unwieldy (even if we allowed consolation shots at the noses of Rumsfeld, Cheney, Rice, Snow, McCain, Lieberman, et bloody al). —So I agitate instead for hearings, and impeachment; justice, not vengeance.

They really are quite different.

Calling all Chinese freebooters.

Y’know, I’ve been wondering why The American Shore, Delany’s book-length study of Disch’s “Angouleme,” is so hard to come by. Now I know.

What if my gold be wrapped in ore?

None throws away the apple for the core.

But if thou shalt cast all away as vain,

I know not but ’twill make me dream again.

“He would be as happy as anyone to be rid of these men. They frighten him as much as they frighten everyone else.”

I was going to say something, anything about Orson Scott Card’s latest exercise in one-state-two-state-red-state-blue-state (here, but also here, here, here, here, here, here, and here). But then I remembered I’d already quoted what somebody else had to say:

Unsuccessful in war and unable to adjust to a troubled peace, Weimar’s visionaries dismissed what was for them an overly complex, difficult, and demoralizing reality and indulged in elaborating fantasies of a vicious war of revenge that cast them in the role of conquerors. In their literature these angry men gave vent to primitive wishes for the annihilation of France, England, the United States, or whomever else they pictured as Germany’s enemy. But the war visions of the 1920s were not merely the self-serving fabrications of isolated malcontents. Instead of being left to dissipate in the realm of dreams, daydreams, and semireligious entrancement, the visions of revenge and renewal were converted into a literature of mass consumption. The published fantasy—often a quirky mixture of adventure story, fairy tale, millenarian vision, and political program—was intended to act as a catalyst inflaming the same type of emotions among the readers that originally elicited the fantasies in the minds of their creators. In this manner, what originated as compensation for the frustrated individual was transformed into a psychological tool, a propagandistic call for militant nationalism and engagement in antirepublican politics. Some of these writers, in fact, were also active as political speakers and agitators.

“History doesn’t repeat itself,” said Mark Twain, “but it does rhyme.” —Except, of course, he didn’t, and anyway, rhyme’s gone all out of fashion. Though I wouldn’t trust fidelity or fashion to keep us safe, not from this crew. Remember, “If This Goes On—”

“...until the white thread of dawn appear to you distinct from its black thread...”

I see that David Cunningham, the crypto-Christianist hack who brought us The Path to 9/11, is on his way to Romania, where he’ll be directing The Dark is Rising. —Walden Media hopes to launch another kid-flick franchise to follow the success of its Narnia adaptations.

Sigh.

If he doesn’t mangle the book(s) beyond all recognition, he will at the very least be forced to acknowledge Cooper’s bracingly grim morality: the Light, in the end, is in its purity and extremity as inhumane as the Dark, dragons and nemeses locked in an abyssal conflict largely invisible to us of the track. We can no more directly identify with the Light than we can wholly condemn those who succumb to the Dark. It’s one of those Important Lessons a kid really ought to learn. (Even if I did stay up late on my eleventh birthday. Just in case.) —Heck, maybe Cunningham himself will learn something, wrestling with the material. One can hope.

And even if he doesn’t, and even if he does mangle the book(s) beyond all recognition, at least those books will get into more kids’ hands. So there’s that, I suppose. —Whichever; I’ve got a sex scene to rewrite and a long-overdue boar hunt to choreograph, and a comics convention to attend. Bygones.

“It’s a terrific view,” Jane said. “Worth the climb. But the wind’s made my eyes water.”

“It must blow like anything up here,” said Simon. “Look at the way those trees are all bent inland.”

Bran was gazing puzzled at a small blue-green stone in the palm of his hand. “Found this in my pocket,” he said to Jane. “You want it, Jenny-oh?”

Barney said, gazing up over the hill, “I heard music! Listen—no, it’s gone. Must have been the wind in the trees.”

“I think it’s time we were starting out,” Will said. “We’ve got a long way to go.”

Appositional.

This isn’t a picture of Wormwood.

I’m not sure why I keep coming back to the decadent espionage thrillers of the ’70s for popcorn reading, these days. Maybe because we were much more sophisticated then? We handled it all—oil crises, Mideast flareups, terrorist hijackings, the existential struggle of the individual against an inevitable subsumption within this bureaucratic matrix, or that—we handled it all with so much more aplomb then than now, it seems. (This is as false as any other comparison of one decade to another. Allow me a minor pecadillo.) —I’m not sure why I keep coming back to Trevanian and MacBeth, in particular. The one so appallingly heartsick beneath its po-faced satire; the other so inadvertently ridiculous beneath its literary pretensions. (That one still managing to naught itself in the belly of the whale Annihilation, but I’m inexcusably referencing an inside joke hermetically sealed. —The first, of course, seeks to return to God by moving shibumily with God, knowing all the while it never can, but like I said, inexcusable, and dragging God into this will not help.)

It?

He? His? (She, hers?) (Penn’s?) —Both of them, of course, united in their queerly doomed battles, taking up the master’s tools against that 20th century grotesque, Bond. James Bond—

The explosions going off today world wide have been smoldering on a long sexual and emotional fuse. The terrorist has been the subliminal idol of an androcentric cultural heritage from prebiblical times to the present. His mystique is the latest version of the Demon Lover. He evokes pity because he lives in death. He emanates sexual power because he represents obliteration. He excites with the thrill of fear. He is the essential challenge to tenderness. He is at once a hero of risk and an antihero of mortality.

He glares out from reviewing stands, where the passing troops salute him. He strides in skintight black leather across the stage, then sets his guitar on fire. He straps a hundred pounds of weaponry to his body, larger than life on the film screen. He peers down from huge glorious-leader posters, and confers with himself at summit meetings. He drives the fastest cars and wears the most opaque sunglasses. He lunges into the prize-fight ring to the sound of cheers. Whatever he dons becomes a uniform. He is a living weapon. Whatever he does at first appalls, then becomes faddish. We are told that women lust to have him. We are told that men lust to be him.

We have, all of us, invoked him for centuries. Now he has become Everyman. This is the democratization of violence.

That isn’t a picture of Wormwood, either. (It may or may not be a picture of Jerry Cornelius, but then most things are. I can’t decide, though, if it’s a picture of Mister Six, or King Mob. It must be one or the other, right?)

But this isn’t about that; not yet, anyway. It’s mostly about Wormwood. Or at least the last few paragraphs of his life. —I was 11 or 12, and looking for something to read, and picked up The Eiger Sanction, because, hey, more spies. And was introduced in the opening bit to the hapless Wormwood, whose foolishness, while contemptible, still seemed to draw an undeserved measure of scorn from the ostensibly neutral third-person omniscient. What a prick, I said to myself, taking Wormwood’s side against a narrator he would never know. (And thereby learning a lesson it would take years to recognize.)

But, as I said, his last few paragraphs in this vale of tears:

As he climbed the dimly lit staircase with its damp, scrofulous carpet, he reminded himself that “winners win.” His spirits sank, however, when he heard the sound of coughing from the room next to his. It was a racking, gagging, disease-laden cough that went on in spasms through the night. He had never seen the old man next door, but he hated the cough that kept him awake.

Standing outside his door, he took the bubble gum from his pocket and examined it. “Probably microfilm. And it’s probably between the gum and the paper. Where the funnies usually are.”

His key turned in the slack lock. As he closed the door behind himself, he breathed with relief. “There’s no getting around it,” he admitted. “Winners—”

But the thought choked in mid-conception. He was not alone in the room.

With a reaction the Training Center would have applauded, he popped the bubble gum, wrapper and all, into his mouth and swallowed it just as the back of his skull was crushed in. The pain was very sharp indeed, but the sound was more terrible. It was akin to biting into crisp celery with your hands over your ears—but more intimate.

Damn.

Okay, “but more intimate” is arguably overkill, but still: Jesus. I shuddered (then and now) and dropped the book and haunted for years by that onomatopoeic image, I didn’t pick up Trevanian again until high school, when I read Shibumi, and kept saying, damn, this is like The Ninja, only better.

As you know, Bob.

One might think that the Laws of Probability would mandate that, without any intelligent input, 50% of the time the events in our world would lead to benefits for mankind. In a strictly mechanical way, life in our world ought to have manifested a sort of “equilibrium.” Factoring in intelligent decisions to do good might bring this average up to about 70%. That would mean that humanity would have advanced over the millennia to a state of existence where good and positive things happen in our lives more often than “negative” or “bad” things. In this way, many of the problems of humanity would have been effectively solved. War and conflict would be a rarity, perhaps 70% of the earth’s population would have decent medical care, a comfortable roof over their heads, and sufficient nutritious food so that death by disease and starvation would be almost unheard of. In other words, human society would have “evolved” in some way, on all levels.

The facts are, however, quite different.

—Laura Knight-Jadczyk, The Secret History of the World and How to Get Out Alive

No, wait, I’m sorry. It’s pretty much exactly the size of a walnut.

Back in March, I committed one of Roy Edroso’s cardinal sins: I snarked off on Harvey C. Mansfield’s Manliness, having only read a couple of the lit world’s equivalents of the trailer. Sorry, Roy. —Well, I still haven’t read it (see life, shortness thereof), but Martha C. Nussbaum has, and oh my dear sweet Lord. (Via; via.)

The grammar of ornament.

Actually, the poster in the window of the Meier & Frank is worse, much worse: she’s lying on her back on that zig-zag couch thing, coy-defenseless, chewing on her come-hither pencil.

It’s part of a Macy’s (née Meier & Frank, and that’s a whole other kettle of fish) promotion, complete with a crappy Flash-based website and tie-ins to crappy bands you’ve never heard of with albums you’ll never hear to flog. Aspiring poet. Aspiring celebrity chef. Aspiring indie filmmaker. Aspiring editor-in-chief. All of them aspiring to do little more than dress and accessorize the part (what else could they do to convince you of their worth, since all you’ll see is a single still image in a store window?): callow images of callow youths aspiring to little more in truth than flattering snark from a Nick Denton website. (The aspiring poet is spot-on, an unholy cross between Jonathan Safran Foer and Leotard Fantastic.) —And ordinarily, I’d be laughing at this joke that can’t figure out who the punchline is; ordinarily, I’m well-enough inured.

But aspiring therapist?

(That’s what it says, there in the white box. “Aspiring therapist.”)

The other callow youths all have the accessories of their aspirations: a sleek little digital camera, a sleek kitchen set, a not-at-all sleek library of serious-looking tomes bought by the yard from the Strand, mockups of sleek magazine covers to be marked up. All our aspiring therapist has is her couch and her pencil and her fun, short-sleeved tee: Let’s Play Doctor. And her patient, of course. Who else you think she’s looking at, bub? All coy-defenseless and come-hither pencil like that? —It’s a sexy nurse joke gone off, therapy and sex and nurture and desire and love all snarled and confused, projection and projector, subject and object inextricably mixed up: who’s aspiring to what, here? This pose isn’t Dr. Melfi, it’s Tony Soprano’s fantasy of Dr. Melfi, and I shudder and turn away and stalk off with a scowl on my face. The other callow images make me snicker; even the aspiring celebrity chefs are Bobby Flay’s fantasy of what it’s like to want to be who he is. But this one makes me angry.

(Is it just me? I dunno. Think about what the image is telling you you should want, or want to be. Just ignore it? Maybe, perhaps it’s best, King Canute and all that, but first slip Mary Daly’s lens in place for a moment: ASPIRING THE/RAPIST. —Whose idea was this, anyway?)

Adam and Eve on a raft.

To learn anything worth knowing requires that you learn as well how pathetic you were when you were ignorant of it. The knowledge of what you have lost irrevocably because you were in ignorance of it is the knowledge of the worth of what you have learned. A reason knowledge/learning in general is so unpopular with so many people is because very early we all learn there is a phenomenologically unpleasant side to it: to learn anything entails the fact that there is no way to escape learning that you were formerly ignorant, to learn that you were a fool, that you have already lost irretrievable opportunities, that you have made wrong choices, that you were silly and limited. These lessons are not pleasant. The acquisition of knowledge—especially when we are young—again and again includes this experience. Older children tease us for what we don’t know. Teachers condescend to us as they instruct us. (Long ago, they beat us for forgetting.) In the school yard we overhear the third graders talking about how dumb the first graders are. When we reach the third grade, we ourselves contribute to such discussions. Thus most people soon actively desire to stay clear of the whole process, because by the time we are seven or eight we know exactly what the repercussions and reactions will be. One moves toward knowledge through a gauntlet of inescapable insults—the most painful among them often self-tendered. The Enlightenment notion (that, indeed, knowledge also bring “enlightenment”—that there is an “upside” to learning as well: that knowledge itself is both happiness and power) tries to suppress that downside. But few people are fooled. Reminders of the downside of the process in stories such as that of Adam and Eve can make us—some of us, some of the time, because we are children of the Enlightenment who have inevitably, successfully, necessarily, been taken in—weep.

We say we are weeping for lost innocence. More truthfully, we are weeping for the lost pleasure of unchallenged ignorance.

—Samuel Delany, “Emblems of Talent”

Words are mere sound and smoke, dimming the heavenly light.

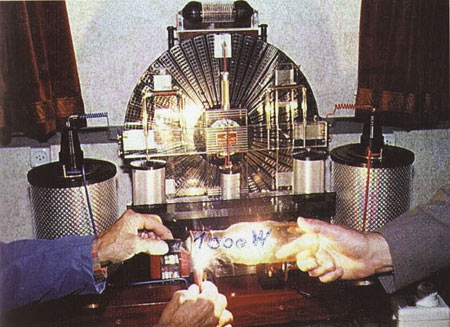

I left Methernitha that day with many questions buzzing through my mind. What if I asked to become a member? Would I be accepted? Would they let me see it then? Would I find out how the machine functioned, and whether trickery was involved? How long would it take to gain their trust? Stefan Marinov, a Bulgarian physicist and free-energy inventor, joined Methernitha and for many years attempted to understand how the machine worked. He claimed to be privy to the secret of the device, but he could not convince the group to share their knowledge with outsiders. In the summer of 1997, he leapt to his death from a library window at Graz University; his suicide note ended with: “feci quod potui, faciant meliora potentes” (“I did what I could, let those who can do better”).

Soon after making my pilgrimage to the Methernitha, I heard about a conference devoted to free energy to be held in Berlin. Looking down the schedule, I was excited to see that there would be a presentation of a Testatika. I immediately booked a place and bought a plane ticket. When the time came, a somewhat half-heartedly constructed machine was described as a demonstration device, created to rule out certain hypotheses of the Testatika’s design—to show how it didn’t work. When I spoke to him after his talk and explained my ambitious quest to build my own working version of the Testatika, he earnestly recommended that a thorough reading of Gœthe’s Faust might be the best way forward.

—Nick Læssing, “Something for Nothing”

Cabinet issue 21—Electricity

This machine bugs liberals.

Say, Fred, I heard Lyndon is forming a new Federal agency.

Yeah? What’s that?

It’s going to be called the Poverty Relief Agency.

Oh, that’s nothing new, Bobby Baker’s headed that department for years.

Zing?

Down in Havana, 90 miles from our shore

Lies an army of Commies and Fidel Castro

We were going to remove them, the plans were all made

We’d help with the airplanes on invasion day

But you know the Liberals and the CIA

They agreed with Adlai, take the airplanes away

So the brave freedom fighters were destined to fall

’Cause we didn’t answer when we heard their call

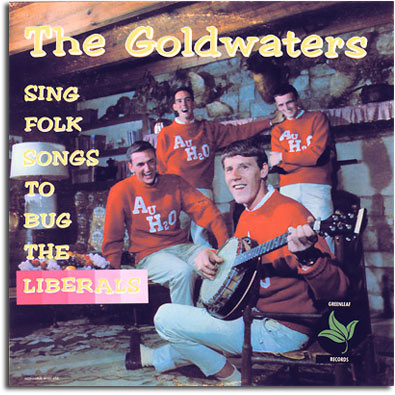

—the Goldwaters, “Down in Havana”

Rick Perlstein’s always worth reading; the Design Observer’s running an essay of his that the New Republic couldn’t be bothered to put online, so go, read “What is Conservative Culture?”

Conservative culture was shaped in another era, one in which conservatives felt marginal and beleaguered. It enunciated a heady sense of defiance. In a world in which patriotic Americans were hemmed in on every side by an all-encroaching liberal hegemony, raw sex in the classrooms, and totalitarian enemies of the United States beating down our very borders, finally conservatives could get together and (as track twelve of the Goldwaters’ Folk Songs to Bug the Liberals avowed) “Row Our Own Boat.”

But now conservatism has grown into a vast and diverse chunk of the electorate. Its culture has become so dominant that one can live entirely within it. Shortly after the Republicans took over Congress in 1994, a Washington activist could, if he so chose, attend nothing but conservative parties, panels, and barbecues; a recent Pew Research Center study suggested that partisan divisions are increasing at the community level. And yet, far inside these enclaves, conservatives still rely on the cultural tropes of that earlier period: At one living room “Party for the President” in 2004, a woman told me, “We’re losing our rights as Christians. ... and being persecuted again.” The culture of conservatives still insists that it is being hemmed in on every side. In Tom DeLay’s valedictory address, as classic an expression of high conservative culture as ever was uttered, he attributed to liberalism “a voracious appetite for growth. In any place or any time on any issue, what does liberalism ever seek, Mr. Speaker? More. ... If conservatives don’t stand up to liberalism, no one will.”

How to explain these strange continuities? And what does it say about the politics of our own time? Kirk offers no answers, because what holds the movement together isn’t its intellectual history but its cultural one. Folk Songs to Bug the Liberals is this mystery’s Rosetta Stone.

Bugging liberals, you see, being bugged by liberals, is not incidental to conservative culture, but rather is constitutive of it—more so than any identifiable positive content. Seeing Republicans appropriate liberal-sounding rhetoric on immigrants and education and getting credit for it—even while their policies corrode public education and also stoke an anti-immigrant backlash—bugs the hell out of the liberals. Which is, for Karl Rove no doubt, part of the calculation. Rove knows that the pleasure of watching liberals’ heads explode is the best way to keep his team rowing in the same direction.

Two things struck me, reading this: first, of course, appropriation isn’t only done to fuck with our the other side’s heads. When you start to believe your own bullshit, that you really are beset on all sides by an implacable foe, when you’re out there fighting dragons every day, you start to ask yourself what it is they’ve got that you don’t; you start to wonder if maybe you shouldn’t become a little draconic yourself. You say things like, “They have Joan Baez, who do we have?”

It was Dr. Fred C. Schwarz of the Christian Anti-Communist Crusade (CACC) who acted as [Janet] Greene’s “Col. Parker” and molded her into his very own Anti-Baez. As reported in The Los Angeles Times, on October 13, 1964, Schwarz unveiled his new musical weapon against Communism at a press conference at the Biltmore Hotel in LA. With Greene at his side, Schwarz stated to the assembled press that he had “taken a leaf out of the Communist book” by adding a conservative folk singer to his organization. “We have decided to take advantage of this technique for our own purposes.” He then added, “You’d be amazed at how much doctrine can be taught in one song.”

The second thing was how old the conservative schtick is. They were hating on the Clenis back in 1964.

Say I saw a new a great new play on Broadway last night, it’s called The Doll House.

Is that the Rodgers-Hammerstein show?

No, it’s a Profumo-Baker production.

Must have been quite a comedy!

Might call it a farce!

Rimshot, motherfuckers. Rimshot.

Oh, right.

I was—“procrastinating” is such an ugly word—I was organizing some notes, looking over the list of proposed titles for upcoming fits and remembering which ones I’d found epigrams for and which ones I hadn’t, when I tripped over “Frail,” there between an as-yet unnamed bit at no. 14 and “Plenty” at no. 16.

“Frail.” Hadn’t that been the one with the O’Brian quote? Aubrey to Maturin, or Maturin to Aubrey, one of ’em anyway laughing at what little it is that separates quickness from death? Which the hell book was that from? And why isn’t the quote in the neat little text file I’ve got of all my other epigrammic candidates?

So I opened up the various other text files I’ve accumulated over the years where notes have been stashed and squirreled away, and searched them with the various search tools at my disposal, looking for “frail.” Bupkes.

Did I forget maybe to put it somewhere? Noted it en passant, said to myself, oh, hey, keen, let’s remember to come back and get this later, okay? And then forgot? As it wouldn’t be the first time.

Okay. Okay. We could go look for it. Except I ran across it the last time I was bingeing through the first seven or so of the Aubrey-Maturin books, and I have no earthly idea which one it was in. And I don’t remember enough of the context to make skimming at all viable. Not through seven books. (Maybe I should start bingeing again? Put down The Orientalist and Evasion and Civilizations Before Greece and Rome and The Demon Lover and pick up Master and Commander for another go-round, grimly determined to pounce this time?)

I think I was actually typing “frail” in the Seach Inside the Book! feature over at Amazon when it hit me: maybe I’d written it down. You know, on paper. With a pen. In the main black notebook I’ve been using when I’m not, you know. Near a keyboard.

Found it in two: “Bless you, Jack, an inch of steel in the right place will do wonders. Man is a pitiably frail machine.” —Although I still don’t know which book. Or what context. Oh, well.

(At least I got a blog post out of it. Now. What in hell am I going to quote for “Surveilling”?)

Althæaphage.

I got an email here. Uh, “Rush,” uh, “now that two of our own have been tortured and murdered by the terrorists in Iraq, will the Left say that they deserved it? I’m so sick of our cut-and-run liberals. Keep up your great work.” Bob C. from Roanoke, Virginia. “PS, I love the way you do the program on the Ditto Cam.” [Laughter.] I read… no, I added that! He didn’t, he didn’t put that in there. [Laughter.] You know, it—it’s—I—uh… I gotta tell ya, I—I—I perused the liberal, kook blogs today, and they are happy that these two soldiers got tortured. They’re saying, “Good riddance. Hope Rumsfeld and whoever sleep well tonight.” I kid you not, folks.

Do I even need to tell you that not a single liberal kook said anything of the kind?

It’s not that they lie. It’s not even that they lie so brazenly, so completely, so shamelessly. It’s that people believe them. It’s not that if only we were speaking out against their lies with more volume and vigor and vim. The indisputable fact of us, being where we are and doing as we do, is enough to give them the lie direct. But the people who believe them don’t pay any attention, and if they do happen across us, they don’t listen. They don’t have to.

Go, Google Abu Zubaydah. Read up on how important he was: a top Bin Laden deputy, al-Qaeda’s top military strategist, their chief recruiter, the mastermind behind 9/11. He’s thirty-five. Two years younger than me. We caught him in 2002. He’d been keeping a diary for ten years, written by three separate personalities. His primary responsibility within the foundation was to make plane reservations for the families of other operatives.

“I said he was important,” Bush reportedly told Tenet at one of their daily meetings. “You’re not going to let me lose face on this, are you?” “No sir, Mr. President,” Tenet replied.

So we tortured him. We tortured him, and he told us all sorts of things about 9/11, and over a hundred people we’ve since indicted on the strength of his coerced word, and “plots of every variety—against shopping malls, banks, supermarkets, water systems, nuclear plants, apartment buildings, the Brooklyn Bridge, the Statue of Liberty. With each new tale, ‘thousands of uniformed men and women raced in a panic to each… target’.”

And so, Suskind writes, “the United States would torture a mentally disturbed man and then leap, screaming, at every word he uttered.”

At least the president didn’t lose face.

As above, so below: the self-similarity of the wingnut function; string theory for echthroi. Too much has been swallowed ever to turn around and come back up; it’s basic human nature to prefer being wrong to ever admitting one might not have been right. (The sort of human nature one is supposed to outgrow, yes, but.)

“Ignorance is a condition. Stupidity is a strategy.” Cliché? Hell, it’s a shibboleth: Welcome to the Reality-based Community. —Ignorance we can deal with, with the talking and the listening and the reasoning and the debating and the citing. Stupidity requires a different approach. Pathological liars so epically insecure they’ve made up their own network called “Excellence in Broadcasting” and call themselves “America’s Anchorman”? That shit writes itself, but our real fight’s altogether elsewhere.

Neither the first word nor the last on profanity, disputation, anger, and civility for bloggers.

The Dragonlord held the blade up, and said, “I was given this weapon of my father, you know.” He studied its length critically. “It is called Reason, because my father always believed in the power of reasoned argument. And yours?”

“From my mother. She found it in the armory when I was very young, and it is one of the last weapons made by Ruthkor and Daughters before their business failed. It is the style my father has always preferred: light and quick, to strike like a snake. I call it Wit’s End.”

“Wit’s End? Why?”

“Well, for much the same reason that yours is Reason.”

Piro turned it in his hand, observing the blade—slender but strong, and the elegant curve of the bell guard. Then he turned to Kytraan and said, “May Reason triumph.”

“It always does, at the end of the day,” said Kytraan, smiling. “And as for you, well, you will always have a resort when you are at your wit’s end.”

“Indeed,” said Piro with a smile, as they waited for the assault to commence.

—Steven Brust, The Viscount of Adrilankha