God, hes left as on aur oun.

When you get caught

Between the Moon and

Second person, chat. I just don’t know. —Oh, it can be done well, anything can be done well, but the curve on second person is some kind of steep. Comes in three basic flavors, the second person: there’s what you might call diegetic second, where who’s being addressed is a specific second person, firmly ensconced in the story as a character themselves, so that it’s really more of a text within the text, you’re distanced from the point of address—it might as well be an exchange you’re eavesdropping, an epistolary you’ve somehow intercepted. —The next you might call more of a diffuse, a second person that, yes, is addressed to you, Dear Reader, but not too specifically: there’s entirely too many of all of you, and far too wonderfully varied; best to be disarmingly vague—and so, in an heroic effort not to break the spell, it can all-too-often never manage to cast one in the first place. —The third second person? Direct: an attempt to square the circle and have it all, the author reaching out of the text to grab you, yes you, Gentle Reader, by your lapels, but also the author would insist on the lapels to be grabbed, the type and tailoring, the heft in the hand, particular lapels suited for the specific you the author has in mind, a you you’re dragooned into playing, will you or nill you: it can’t help but hector, this voice, and no one likes being hectored, though even this can be done effectively, even well—one thinks of Eddie Campbell’s How to be an Artist, told in a striking second-person imperative, but that’s comics, and there are so many other things happening to détourn that voice. —Like I said. It’s hard.

So when I tell you The Spear Cuts Through Water is written in the second person—

(“You were thirteen, you think,” you’re told, quite imperiously, and I don’t know about you, but while I’m game enough to pretend to have memories I’ve never had, I’d just as soon decide for myself how reliable they are. Though I must admit I remembered this particular directive as landing rather more forcefully that it does upon re-reading; I was surprised by how—mild?—it turned out to have been. Thus, a grain of salt.)

—I mean, it isn’t, not really: it’s actually a first-person text. I mean, yes, every narrative is necessarily written in the first person, but Spear’s only somewhat coy as to this fundamental truth: your narrator’s there, on the page, on the stage, referring to themself always in the third person as “this moonlit body” (never “a,” or “the,” or “that” moonlit body, but always and reflexively “this”): the love-child (soi-disant) of the Moon and the Water, impresario and headliner of the showstopping antics of the Inverted Theater, that reflection of an impossibly tiered pagoda floating on the surface of the Water, bathed in the light of the Moon.

This is the structural triumph of the book, and what I greatly admire: that the epic as such is a theatrical production, drama and dance performed in that Inverted Theater in a dream that you’re having, told to you, narrated necessarily because it’s actually unfolding from the pages of the book in your hand, written by Simon Jimenez, but set that aside, because as you’re dreaming the story you’re reading, this moonlit body reminds you of your memories, memories of your much-later life that spark, that are sparked by, incidents in that story, this epic of the old country from so long ago. These layers add a richness that carries what’s really a rather focused (and single-volume) work just over the threshold of epic, but the movements between and among them are so surefooted that you’re never lost, never bogged down in metashenanigans: you marvel, instead, as background characters, bit players, minor figures, NPCs (in the [shudder] parlance of our [shudder] times)—as the story’s performed, the actors playing them in the Inverted Theater will step up to speak for a moment, a passage, a phrase, a snatch of internal monologue become spotlit soliloquy, a bit of italicized free indirect slipped in to trouble the narrative flow, to comment, contest, open it up, all these non-protagonists, from the usual monotone of one word set carefully, deliberately after another toward something more of a polyphony. Such a simple trick! But deceptively so: it’s only the theatrical conceit that allows it to work as well as it does, the artifice of performance excusing the artifice of italics, and of the courtly stilt needed to better fit with the flow of this moonlit body’s narration—appropriate enough for an epic, to be sure, but not so much for a glimpse of a stream of consciousness, unless, of course, that stream’s been polished by rehearsal, shaped and timed to fit: a performance, each of them, however glancing, however brief.

Marvel, then, and marvel again, as, once established, these moves are elaborated: the Moon’s dialogue, say, which is handled the same way as these extra-narrative irruptions; when She speaks, She steps up (or the actor playing Her) to tell you what it was She said, back in the day, impressively at once more immediate and yet more distancing. Notice that neither of the protagonists is given a chance to directly address you—not until She passes, passing on a modicum of Her power, which they use, this technique, this trick of the book, to talk to each other—a graceful melding of form and function, all built before you as you read—and when it all comes together, levels and tricks and elaborations folded together to make the apotheosis if not the climax of the book, as the narrative conjures a deceptively simple trick of the theatre to collapse event and representation, story-time and telling-time, actant and audience, reaching up to grab you, yes, you, you there, by whatever lapels you’re wearing, and haul you in—it’s electrifying. For this, this marvelous conceit, Spear deserves every accolade it’s received, and very much a prominent place in whatever broader conversations we have going forward about technique, about prose and structure, form, novels and epics, you know: fantasy.

But. Having said all that. I feel a little sheepish, here, I mean, every word is true, don’t get me wrong, but. I just, y’know. Didn’t like it very much. The book.

Some of that—a lot of it, really—is due to the climax, which has to follow the admittedly staggering act of that apotheosis. Two new characters crowd the (metaphorical) stage, both mentioned previously, to be sure, but nonetheless focus is pulled as the work required to bring them on gets done, work that maybe should’ve, could’ve been done earlier, along the way (not so much Shan, daughter of Araya the Drunk from all the way back at the beginning, to whom the protagonists are to deliver the titular Spear, but the Third Terror is a magic trick the book tries to pull off not so much by misdirection, hoping you’ll maybe forget for a time, but instead by apparently forgetting itself until this last-minute dash)—all for the sort of action-packed hugger-mugger that passes for third acts these days in superheroic action flicks, a widescreen smashemup that works even less well in prose, no matter how artful. Armies clash without the city walls! Within, the Third Terror has become a kaiju, obliterating buildings, tossing back people like popcorn shrimp! The ocean has withdrawn, stranding treasure ships and shoals of dying fish! An unimaginable tsunami, impossible to withstand, is just hours away, still hours away, yet already it swallows the horizon! To anywhere, one of the background characters tells you in their moment in the spotlight, of where the supernumeraries all thought to flee; It was too much. There were five ends of the world, and to run away from one meant running into another, and damn, you feel that, but not in a way that’s maybe intended. Why five ends of the world, when but one is more than enough? (Shades of thirty or forty sinking Atlantises, or those in the path of a super-typhoon.) —This apocalypse goes to eleven!

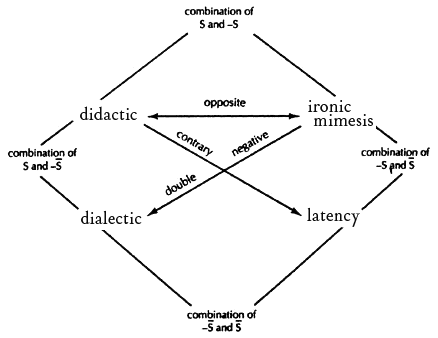

But a climax is made from what’s come before, and though the book’s conceit is a magisterial wonder, I’m afraid it’s elsewhere thinned, and weak. —The Spear Cuts Through Water is a portal/quest fantasy, to reach for our Rhetorics: one that broadly straddles the didacticism of that mode to lean hard on both the knowing dialectic of the liminal (it may seem odd, to refer to something so openly, baldly itself as “liminal,” but the book blithely skips back and forth over every limen that would mark its place) as well as, and but also, I think, to its detriment, the ironic mimesis of the immersive:

The epic (as such) begins with a brashly thrilling overture, already in incipient crisis, plots a-swirl about the court and a garrison, a deeply seeded rebellion apparently a-brew, only for the table so deftly set to be entirely upended by an explosive inciting incident and you’re off to the races, rather literally, across the breadth of the old country, for the next five days—a terribly focused epic, as you might could see; the pace and the scale of it would tend to militate against the sort of didactic lore-dumps (no matter how artful) that are a hallmark of the portal/quest. And, as you know, Bob, most folks don’t so much go around explaining to each other the differing details of what they’re seeing and doing as they go about their day, simply for your benefit, Dear Reader. Thus, the logic of ironic mimesis, as they take for granted what you might find fantastical—but! Consider the tortoises:

All of this theater for the benefit of the creature perched on the high chair.

The tortoise’s gaze was set on the First Terror. “The Smiling Sun wishes to know your thoughts,” the mad creature giggled. “From all the evidence laid before you, to what side of the line does your heart lean?”

The Terror looked up at his father’s surrogate and then down at the wet dog of a man in the center of the room. Thirty-three years. And without a further moment of consideration, he said, “My Smiling Sun, this man is guilty.”

The tortoises turn out to be rather important, to empire and story, and this is your first—well, it’s not really a glimpse, is it? You don’t really see anything, not in this scene, just a handful of words, references to a tortoise, a mad, giggling creature, the Emperor’s surrogate, but without any attempt to body forth the referent (an aimless bobbing of a too-small head, light glancing from the shell of it, the smell, for God’s sake, or what the actors in the Inverted Theater might be doing, to conjure this image for you)—well, you’re at a loss. You’ve seen that everyone at court wears stylized animal masks, and this is (I believe) also the first indication that certain animals here in the old country can speak—I, at least, for a couple-few pages, thought maybe it was a eunuch (court; giggling) in a tortoise mask perched on that high chair. (How, exactly, can a tortoise perch, per se, anyway?)

There are other such lacunæ, some eventually remedied, some not (I still don’t have a clear idea of how the Road Above and the Road Below work, say), all adding up less to a sense of playful, ironic reserve than a frustrating lack. And there’s a slapdashery to some of the details that are presented: eight emperors have ruled since the Moon stepped down out of the sky; eight generations, as each has demanded a son of the Moon, and raised him up in turn; eight Smiling Suns that have beaten down on the old country in an endless, rainless summer—I think? It’s hinted, alluded to, but never quite clear, or as clear as it should be, whether a drop of rain has fallen in all that time, but certainly, it’s hot, it’s dry, but never perhaps as dry as it could be? Should be? Might? —It doesn’t feel like a world that has learned to live without something so important as rain, or moonlight: eight generations also without a Moon—just an empty starless patch of sky known as the Burn—but you’re told at one point that “The Burn in the sky smoldered like a black moon above their heads.” A strange simile, to liken the lack of a thing to the thing long gone.

There’s a tension, between a looser, goosier f--ry tale world, a knowingly artificial, liminal world, and a world more brutalistically immersive, a tension you can play with, certainly, build things from, and with, anything can be done, and done well, but of course it takes work, and consideration, neither of which I don’t think really got done here, not as to this angle, and maybe you disagree, maybe it didn’t bother you all that much, maybe you’d say it’s subjective, but then there’s page 58 of the 2023 Del Rey paperback edition:

Through the courtyard he walked, slipping back into his sleeveless shirt as he passed the night shift at work. Soldiers unracking weapons and polishing the blades and spear tips smooth with oiled cloth, bouncing moonlight off the curved metal.

Eight generations the Moon’s been locked away in a cave under the mountains, and they’re bouncing what, now? —A small and simple error, sure, a slip of the metaphorical tongue, reaching along well-worn grooves for the sort of detail that this sort of phrase in that sort of scene would usually call for, but: in a liminal, ironic mode, where you’re on guard for the slightest clue as to what the ostensible narrative maybe pointedly isn’t telling you, such a slip can be fatal to the knowing dialectic between the writer, yes, and you, the reader. Moonlight? you’re thinking, wait, is the Moon’s absence maybe not really the absence of a moon? Is there something unexpected going on? What could it be? and by the time you trip to the fact that it’s nothing, just a slip, the damage has been done.

But if it had been caught? If it had been torchlight instead, or starlight? If it hadn’t bedeviled me as it did, if I’d been in a more charitable mood, or mode? Still: the world of this epic, the old country under the Smiling Sun, is unrelentingly brutal and viciously violent. The epic begins in incipient crisis, yes; it is—relentlessly, viciously—focused, on the events of the next five days; such a scope and pace will lend the proceedings a tendency toward packing on the action, and that it does, to such an extent that when it seeks to vary the tone, to reach for a moment of shock, or awe, or o’erweening cruelty, it overloads to what becomes a cartoonish degree: on the morning of the second day, as the protagonists pole their stolen boat through the waterlands of the Thousand Rivers, they come across a fishing village that has been massacred:

It was blood. Everything was painted in blood. It killed us all. As if someone had taken great big bucketfuls of blood and doused the dock boards with it, and the boats, and the walls of the houses that made up this small and now silent village. It came through the windows. It broke through the doors. An arm hung off the side of the dock. When their rightmost pontoon bumped into the dock strut by accident, the arm slipped off the edge and gulped into the water.

It’s arresting—in the moment. The protagonists react—discomfitted, appalled—in the moment. But it fades as you proceed, given what you’ve already seen, what you will see, violences great and terrible and intensely, cruelly personal, the massacre at the Tiger Gate, the slaughter in and among the barges of the Bowl, bodies folded into boxes and coins of flesh, the Second Terror’s horrifically capricious punishment of his dancers, the farmers ridden unnoticed beneath the hooves of the First Terror’s horses because they did not get out of the way fast enough, and the farmhouses obliterated with the flick of a wrist because they were in the way at all, and so that passage through the fishing village, just as dead and gone as all the others, has just as much impact on you, on the protagonists, as anything, everything else that’s gone on, that goes on without even another mention until, in the climax, it’s revealed, in the course of revealing the Third Terror, that he was the one who massacred the village, they would’ve assaulted the protagonists, you see, murdered them for their boat, for their outlandishness, for the peacock tattoo, for whatever reason, and so he removed them from consideration, fft! A puzzle-piece snapped into place here at the end, but whatever satisfaction it might’ve given is lost, the entire puzzle’s indistinguishably soaked in blood, blood! and everywhere there’s screaming and the sound of blows. —Five apocalypses going off all around you here at the end, but what does it matter, really, when you’ve already seen hundreds, thousands of worlds already snuffed out? (How many of those spotlit soliloquies are minor characters relaying or reflecting on the instants just before their violently abrupt ends, or the moments immediately after?)

Thus, the Spear Cuts Through Water, a book I didn’t so much care for, and of which I am intensely, distractingly envious. It’s the only thing I’ve read by Simon Jimenez; I’m curious, now, to see what he did with his first book, The Vanished Birds. —I’m even more curious to see what he does next.