Flexible fetishry.

Just going on record as agreeing with the eminently sensible Ampersand (and thus, by extension, former housemate and all-around mensch, Chas.): heterosexuality (or homosexuality) is best viewed as something of a fetish. —Some indulge in it to a greater degree than others, and some not at all, but it’s basically a means of fixing and focusing one’s desire—something we all do, of course, with this or that (hair color, body size, race and ethnicity, a way of laughing or telling shaggy-dog stories, that thing they do with their wallet chains), for reasons both hardwired (genetically and culturally) and whimsically contingent. —The sex (or gender, depending) of the object(s) of one’s desire(s) is just one more way of focussing, hieghtening, discriminating. (As in taste. Do keep up.) —Do note also that this is not so much a present verity (such things being rather tied to cultural standards and outlooks, and the culture at large being rather, shall we say, hung up on certain issues) as it is an ought-to-be (and given some of those hang-ups I’d agree provisionally that it is better as an end than its promulgation in the here and now is as a means to that end); keep in mind heteroflexibility and its (admittedly) thorny obverse, and always, always take the claims of evolutionary psychologists with a shaker or two of salt.

(Who, me? For the record? Something of a fetish for the opposite sex, indeed, though not so it’s a requirement or anything, and we could spend some time drawing distinctions between actual people and pop culture totems and icons and one’s [my?] differing responses thereto, but we’d get bogged down in stupid discussions of the putative male visual response and endless Schroedinger’s cat-like arguments on what’s a “real” measure of whatever it is we’re trying to measure. —And anyway, I could start throwing up lenses of gender and further confuse the issue: brusque men with small wrists and pungent senses of humor dandied up just this side of effeminate; butch femme women [as opposed, you see, to femme butches] with short unblond hair and little truck with lipstick [odd, to think I’ve forgotten what lipstick tastes like], and you could if you wanted impose the one on the other to see what similarities bleed through, or if a difference [even here] yet vives, but none of it explains the year and a half I spent in my youth enthralled to my best friend’s sister, as gawky tall as I was in her bare feet, with heavy ringletted curls of golden hair cascading down to the small of her back. There’s your “type,” yes, and then there’s the people you fall for, and one must never mistake the map for the thing mapped.)

Ax(e)minster and other inconsequentialities.

The post office downtown has closed. And even though it isn’t the same thing (at all) as the ugly concrete barricades blocking the former parking circle in front of the Edith Green – Wendell Wyatt Federal Building, a makeshift solution to a problem we will always have with us (until we decide otherwise), they’re still signs of the same dam’ thing: that my own personal slice of civic life, the convenience? the dignity? the pride, perhaps, the civic pride of being able to walk a couple of blocks from my office and buy some dam’ postage stamps from what was once the oldest post office in continual operation west of the Mississippi (yes, convenience, too. But a convenience altogether different than being able to buy said stamps at the local supermarket), that my civic life is less important than five parking spaces for 9th Circuit judges; that the desire to be seen doing something quick and dirty and starvation cheap and ultimately utterly ineffectual against a form of terrorism (rental trucks and fertilizer bombs; plastique, if you’ve got militia connections with disgruntled servicefolks, perhaps) that, outside of Ann Coulter columns, is so 1995, that this pissant little gesture (a stroke of a pen, and a dozen concrete barricades, ugly protowalls shaped like long caltrops, like these are the things you cut slices from to make the riprap tumbled at the bottom of commercial jetties, are dumped haphazardly a set distance from the foundation of the building, no cars or trucks closer than this, please) is more important than any pride one might take in appearances, in what tries to pass these days for an agora. At least Napoleon III had the gumption to rebuild the entire frickin’ city, you know?

Slapdash. —This is what I think of, walking down the sidewalk between the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco (Portland Branch) and more of those dam’ barricades.

I’m reading a collection of short stories by Gary Lutz and I like them well enough. He has a flair for sentences that loop unexpectedly, nouns verbified and adjectivals adverbed not for mere ugly convenience (à la businessprech) but for a much more immediate and nebulous effect, and when it works (“I’d awelessly faked my way through a Midwestern graduate school with a dissertation two hundred and eighty-seven clawing, suffixy pages long, all of it embezzled from leaky monographs”) it works quite well indeed, and when it doesn’t (“Every night we let sleep reinflict upon us its formulary and useless terrors. Come morning, it was usually argued that we were out of place, and a map was once again pencilly roughed out”) it doesn’t so much, and though “Street Map of the Continent,” say, leaves a chill wind blowing down your spine, overall it’s mostly grey little anti-epiphanics, straitlaced recountings of the unreasonable reasons behind obsessive peregrinations that end up going nowhere much; things done not because they are done but because the words that make up the telling of them conjure interesting, evanescent new flavors in your mouth. He’s a po-faced absurdist in the same basic school (I’d say; you might say different) as Kelly Link and Ray Vukcevich, but Lutz’s insistence on naturalism (thus far) anchors him, greys him, sends him spinning away from oddball presque vu into obsessive, nattering retreat, but that’s just me tagging him for not doing what he isn’t doing, not for not doing what he’s doing well, which he does do. Still. Link’s witches and Vukcevich’s spacesuits end up paradoxically making their stories more open, more universal, more—more. Real(ish) people reacting appropriately (if one could ever designate what is apropos in such circumstances) to impossible stimuli, rather than people not so real(ish) because they react inappropriately (if at all) to quotidian stimuli—phones that don’t ring, dead-end jobs, that annoying neighbor in the apartment just above you. (Schizophrenia and neurosis, isn’t it?)

But I’m being hard on Lutz, whom as I said I like. Quite. Has an evident love for words and a way with sentences, a sort of brusque chivalry, at once antique and outlandish. —Even if his much-vaunted clarity isn’t, much.

Jenn’s put up some of the first entries in her Explications, some of the world-building elements behind the scenes of Dicebox which (ahem) I’ve had a hand in. One of which I’d mostly forgotten between the writing of it and now: the review of the soap opera to which Griffen is addicted, Forever Between the Light and the Dark. —And aside from the particular point I want to make about Axeminster is the sheer delight I had in coming up with the details: if you want to know what my ur-entertainment is, it’s pretty much this: an anime-bright never-ending steampunk spicepunk glitterpunk Bollywood musical soap opera. Baby, I am so there.

But. Axeminster, Adelaide. The “Axeminster” comes from MacGuyver, of all places, which neither the Spouse nor I had ever watched before. —You have to understand how we get work done, sometimes, especially in the winter: bundled up on the couch, her at the one end, me at the other, under the same afghan (and, if especially cold, a comforter, perhaps), a cat on this lap or that (the other, not so sociable, watching us dreamily from the ottoman), our respective laptops (hers snow, mine tangerine) on tray tables before us (or maybe she’s got the sketchbook, the pencils, the kneaded erasers, and is constantly asking me to hold my hand thus, to laugh so, to turn my head and smile and hold it, just for a moment, there, thanks). The television’s on more often than not, more as hearth than actual focus of attention: flashing color and flickering noise to distract the bits of the brain that would otherwise get in the way of the words you’re writing or the lines you’re drawing with a lot of hemming and hawing and second-guessing. And one of those nights the channel surfing had stopped for one reason or another on TV Land, there at the top of our expanded basic cable dial, where we found an episode of MacGuyver. Maybe it was the opening with the nuclear plant somewhere in the Middle East being MacGuyvered that hooked us, I dunno. But it turned out to be an appallingly amateurish show with those weird, washed-out ’80s TV colors and a terribly hackneyed plot. The fun came from D’Mitch Davis’s portrayal of laconic hitman Axminster, out to get Our Hero—or rather, from the way he was portrayed: a black man nattily dressed in safari-ish gear standing in the back of a jeep bossing a posse of white men in full-on camo-and-safety-orange hunting togs who’d relay the most obvious exposition to him in hastily deferential tones: “He’s just been shot, Axminster!” “Nobody’s here, Axminster!” “It’s coming from over there, Axminster!”—And all of those painfully obvious voiceovers slapped onto location shots filmed MOS and shoehorned into the narrative. The giggles got positively Pavlovian.

Since I was noodling the Forever Between review while half-watching it, the producer became Adelaide Axeminster. —All of which I’d promptly forgotten, utterly, until Jenn asked me to give the piece one more once-over last night before uploading them.

So.

For some reason, there’s a connection in the back of my brain, nebulous and inexplicable but unquestionably there: on the one hand, the difference noted above between Link and Lutz, between schizophrenia and neurosis (as it perhaps were); on the other, the fact that I react to “Full of Grace” almost entirely because of the way it was used at the very end of Buffy’s second-season finale (which was on FX not too long ago; I was cooking dinner, the Spouse taking a post-work bath, and we’ve seen this ep a dozen times, easily, but the commercial break ends at 10 till the hour and here comes the fourth act, Buffy striding down that dawnlit street with a bare sword in her hand, Xander crashing out of the woods with a rock and a lie, and the pasta water’s boiling but it doesn’t matter; the sword fight is thrilling but clumsy—Boreanaz’ stunt double has a completely different hairline, and it’s as-ever painfully obvious when it’s Gellar and when it’s Sophia Crawford—and it doesn’t matter; the dialogue hasn’t aged well in spots and the acting especially at the end with the Scooby Gang standing around hands in their pockets and bandages on their heads is, again, clumsy, and it just doesn’t matter; the Spouse is out of her bath book in hand in her red robe in the TV room dripping and it doesn’t matter, because out of all this somehow the alchemy still works its magic a dozen times over now; it’s still ten of the most shattering minutes ever on a TV show, my God; Whedon teases us with the Worst Possible Ending and then shockingly ups the ante; Buffy kisses Angel one last time and then plunges the sword into him and the look on Gellar’s face as the music crashes to the ground and out of the wreckage crawls Sarah McLachlan’s voice, the winter here is cold, and bitter…), and yet I react to Poe’s “Amazed” for almost entirely inexplicable personal reasons (which won’t stop me from giving it that old college try: it’s the maze, of course, amazing, ha, but it’s the moment when—the song has climbed up out of its nice-enough but still quotidian verse-chorus-verse into an endlessly lifting bridge that’s churning with this undeniable washing waltz of a rhythm—and then the bass and the drums drop out leaving only her voice and the melody carried by I-don’t-know-what, strings, synthesizers, it doesn’t matter, there’s a guitar in there pretending to be a sitar, I think, but so what, the words carried along willy-nill in that waltz: And here by the ocean the sky’s full of leaves, and what they can tell you depends on what you believe… and that’s it; I’m standing on a beach somewhere, the air is cold and full of water and salt and the sound of the waves, endlessly—), and yet—and yet, these two songs, two very different reasons, but the feeling itself is the same, the same: that swooping swelling presque vu that demands attention, that you stop and hold yourself motionless and let it happen to you until it’s past, it’s over, you’re done. And then.

I’m sorry. What was I saying?

A half-satisfied cat being better than none.

Moved mostly to post a couple of searches on which Google (and thus by extension this whole mighty interweb-thingie) failed me today. First, the Multnomah County Library has in storage a book with the tantalizing title: History of remarkable conspiracies connected with European history, during the fifteenth, sixteenth, and seventeenth centuries, by Lawson, John Parker, d. 1852. But it’s in, as noted, storage, and anyway the library is closed on Mondays (thanks ever so much, Mr. Sizemore), so I couldn’t go on my lunch break to figure out whether or not I can pry it out of their hands for a week or so. But! Google would help! And instantly, to boot! Surely a book about so tantalizing a topic will have been read by someone somewhere, and thus naturally enough nattered on about on some obscure webpage. —I’ll at least have a better idea as to whether or not Mr. Lawson’s tome is worth the prying. But even the simplest variation of the title turns up bupkes, and John Parker Lawson, d. 1852 or not, fares little better.

Hmpf.

Second: enjoying immensely The Sword and the Centuries, by Alfred Hutton, FSA—he quotes primary sources extensively, is proving a wealth of delicious trivia about points of honor and fighting with long sharp sticks, and has that wonderful tang to his voice, that admixture of florid vocabulary and dry understatement that makes me weak in the knees. I mean, he uses words like supersticerie—

Well. Google turns up nothing, and the editors of the OED apparently hadn’t read Sword by 1971. —The meaning is clear enough from context:

A certain Gounellieu, a great favourite of the King, had incurred his hatred, and that justly, because this Gounellieu had killed, as it was said, with supersticery and foul advantage, a young brother of his…

...we have seen how various acts of “supersticerie” arose—how a wicked-minded man, feeling sure that his adversary was honest, would appear on the field with a good strong coat of mail concealed under his shirt…

Breaking the word and scrying its entrails helps, too (of course): super and sistere, to stand above, cf. intersices and superstition. Supersticerie does have a supernatural component, given the number of charms duellists would tuck about their person for a chance at that scant edge (and the vociferousness with which they then had to proclaim before God and King or Duke or Marshal they had done no such thing); and so one who depends upon such supersticery (as opposed, say, to mail coats hidden under shirts, or paying one’s buddies to waylay one’s opponent on the way to the duelling ground—also incidents of supersticery) is, of course, a bit superstitious. I like the quality of its movement in logic-space: appealing to extra-legal recourse is, in a sense, standing above the fray. And I like its linkage with another obsolete variant on super-sistere, which the OED had tumbled to in 1971: superstitie, the power of survival. —“The people are the many waters, he turn’d their froth and fome into pearls, and wearied all weathers with an unimpaired Superstitie.”

So there’s my contribution to the interweb-thingie, this week; give it a few days, and the next time someone goes hunting via Google for “supersticerie,” they’ll get something of an answer. One out of two ain’t bad.

But I’m still curious as hell about Lawson’s 150-year-old conspiracy theories. Anyone? Anyone?

The dark time was roasted by hailstones and flames.

The bright time was wiped out by a shadow.

There’s nothing I can do; there’s nothing I can do. Checking the news every five minutes does no one any good. Ripping off Robyn Hitchcock lyrics does no one any good. Giggling madly at slips of the lip in a global gamble with 10-million-people-at-risk-of-starvation chips does no one any good. Listening to the news choppers circle downtown and wondering acidly if the Burnside Free State will rise again tonight does no one any good. Grandly proclaiming that having lost what mattered to very real people we have won what matters to dreams and ideals is doing no one any good. —At least, it’s not doing me any good. Juliet, quoting a 4,000-year-old lament for the fall of Sumer and Urim? I don’t know if it did her any good. I don’t know if it’s doing me any good, though in a way I am—what? Grateful?

Such a little word.

There’s too much history in the air. Twelve years, three presidential terms ago, give or take a couple of months, we were all huddled around a TV in an unheated room in a big old Boston house, watching the bombs drop.There’s a mad sketch we all did, passing a big black sketchbook back and forth, watching that one guy, the human CNN guy, shocked and awed and scared out of his mind, reporting from downtown Baghdad. He went away after a day or so and was summarily replaced by a smug, blowdried little toad with an utterly improbable name. We laughed at him, because it was either that or scream at the phlegmatic silver-haired stentorians insisting, you know, that they just don’t value human life the way we do. And another turn about the widening gyre and here we are again. Deja vu, jamais vu. I know this place, though I have never been here before. I do not know this place, though I have been here many times. (This time? This time, will we finally fall from the lip of one interpenetrating, whirling cone to the apex of the other?)

Hunger filled the city like water, it would not cease.

This hunger contorted people’s faces, twisted their muscles.

Its people were as if drowning in a pond,

they gasped for breath.

Its king breathed heavily in his palace, all alone.

Its people dropped their weapons,

their weapons hit the ground.

They struck their necks with their hands and cried.

They sought counsel with each other,

they searched for clarification:

“Alas, what can we say about it?

What more can we add to it?

How long until we are finished off by this catastrophe?”

I’m going to unplug this thing and kick it in the corner for a bit. Metaphorically, understand. I’ll just be over yonder a ways. Talk amongst yourselves.

Burlesque.

Browsing Blogdex, I stumbled over two lit-crittish burlesques of our current sitch, from either side of the howling divide: that side, and this one. —Unfair, perhaps, but it is rather nice to have one’s prejudices reinforced now and again, isn’t it? (Meanwhile, in the real world—)

That pleasure taken in watching a bladesmith at work,

or, (Snicker-snack).

“And this is the only woman whom I ever loved,” Jurgen remembered, upon a sudden. For people cannot always be thinking of these matters.

That’s from Jurgen, the book currently living in the pocket of whichever coat I happen to be wearing, to be pulled out and dipped into whenever there’s a spare moment, its pages littered with bus transfers marking this passage or that, or the one following:

“Why, it seemed to me I had lost the most of myself; and there was left only a brain which played with ideas, and a body that went delicately down pleasant ways. And I could not believe as my fellows believed, nor could I love them, nor could I detect anything in aught they said or did save their exceeding folly: for I had lost their cordial common faith in the importance of what use they made of half-hours and months and years; and because a jill-flirt had opened my eyes so that they saw too much, I had lost faith in the importance of my own actions, too. There was a little time of which the passing might be made endurable; beyond gaped unpredictable darkness: and that was all there was of certainty anywhere. Now tell me, Heart’s Desire, but was not that a foolish dream? For these things never happened. Why, it would not be fair if these things ever happened!”

(If you happen to note that I’m quoting rather extensively from the early bits, specifically Chapter 4, “The Dorothy Who Did Not Understand,” it’s because the other book in my pocket is The King of Elfland’s Daughter, which I’d been reading til yesterday, when a surfeit of “the fields we know” prompted me to set it aside and cast about for a more bracing tonic. —Not to knock Dunsany, mind; Pegana’s one of my all-time faves. But enough every now and again is enough.)

I’m not sure where I first picked up the name Cabell as one to watch; it may well be that I merely saw the slim, well-used, gorgeously stringent 1940s Penguin paperbacks on the shelf at Powell’s and said, huh. Jurgen and The Silver Stallion have been in my to-read-one-of-these-days pile for a while; and now that I’ve dipped my toe, I can tell I’ve got a new obsession to occupy my spare book-hunting moments. (I’m rather amused if mildly taken aback to discover Cabell’s apparent influence on one my bêtes noires, Robert Anson Heinlein. [We can argue it later and elsewhere if you’re so inclined, and I’ll concede his importance and wouldn’t dream of denying his influence which, after all, is the reason this bête is so very noire. And I’ll even allow as how “The Menace from Earth” has a fond place in my heart and The Moon is a Harsh Mistress is a great book. But but but. Let’s just say for now that much as comic booksters have Papa Jack Kirby, speculative fictioneers have Papa Robert Heinlein, and the comics folks got the better deal by far.] —Not that I’ve much of a leg to stand on at the moment, but based on my familiarity with Heinlein, having skimmed a couple of biographical and critical essays on Cabell, and oohed and aahed over a couple-dozen pages of Jurgen, I’m going out on a limb and saying I think the Grand Master rather tragicomically Missed the Point. Or a Point. And even if one can argue successfully that Heinlein’s ends were largely sympathetic to Cabell’s, his means were quite different—and as the world seems hell-bent on proving beyond the shadow of any faith to the contrary these days, there are no ends. There’s never an end. Only means. But I’m legless and on a thin branch here; keep your salt handy. I will.)

Don’t mind me too much; I’m in the first mad throes of an infatuation. The bloom will fade, I’ve no doubt; it always does. (Nor could I detect anything in aught they said or did save their exceeding folly.) But until then—I mean, Jesus wept, would you look at this? Is it not a splendid rose?

Before each tarradiddle,

Uncowed by sciolists,

Robuster persons twiddle

Tremendously big fists.

“Our gods are good,” they tell us;

“Nor will our gods defer

Remission of rude fellows’

Ability to err.”

So this, your Jurgen, travels

Content to compromise

Ordainments none unravels

Explicitly . . . and sighs.

Projection.

Yeah, I know. Cheap indeed to begin a piece with a definition; it’s usually a sign of desperately padding one’s word count. Just humor me, okay, as I crib this précis of various definitions of Freudian projection culled from, I am assured, orthodox psychology texts:

- A defense mechanism in which the individual attributes to other people impulses and traits that he himself has but cannot accept. It is especially likely to occur when the person lacks insight into his own impulses and traits.

- The externalisation of internal unconscious wishes, desires or emotions on to other people. So, for example, someone who feels subconsciously that they have a powerful latent homosexual drive may not acknowledge this consciously, but it may show in their readiness to suspect others of being homosexual.

- Attributing one’s own undesirable traits to other people or agencies, e.g., an aggressive man accuses other people of being hostile.

- The individual perceives in others the motive he denies having himself. Thus the cheat is sure that everyone else is dishonest. The would-be adulterer accuses his wife of infidelity.

- People attribute their own undesirable traits onto others. An individual who unconsciously recognises his or her aggressive tendencies may then see other people acting in an excessively aggressive way.

- Projection is the opposite defence mechanism to identification. We project our own unpleasant feelings onto someone else and blame them for having thoughts that we really have.

Clear enough, right?

David Brock, of course, is famous enough for asserting that the peculiar vituperation of the current incarnation of the American right (and even, perhaps, their insistence on a vast, left-wing media conspiracy?) is due to projection:

But then there was something deeper that went beyond just partisanship. It went beyond disagreement on the issues. You could only find it in the emotional life of the actual Clinton haters, their own frustration, their own projection of their own flaws onto the Clintons. There’s hardly anyone in the book who wasn’t living in a glass house while they were making all these accusations against the Clintons. I’m not a psychologist, but you have some kind of psychological phenomenon going on where that deep level of emotion and hatred has to do with themselves more than it has to do with anything the Clintons said or did.

Of course, we don’t need to rely on what might or might not be rank psychobabble from a man who admits he isn’t a psychologist to explain what’s going on. There’s a far more prosaic form of projection demonstrably at work, as Nicholas Confessore explains:

When right-wing journalists don’t fall into line, they’re considered traitors, not professionals. In the late 1990s, The Weekly Standard’s Tucker Carlson was nearly banished from the conservative movement for being too critical of strategist Grover Norquist. Meanwhile, The New Yorker’s Sid Blumenthal was banished from journalism for being too close to Bill Clinton. To generalize, conservative pundits assume that establishment media such as the Times are partisan because that’s how their own journalists are expected to operate. They believe Howell Raines runs The New York Times the way they know Wes Pruden runs The Washington Times.

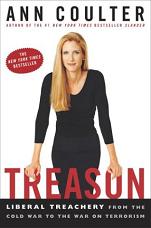

Now, Ann Coulter—

I’ll wait till you stop laughing.

Okay?

Good.

Ann Coulter—stop it!—is, of course, the classic example whenever one brings up the American right wing and projection. Whether it’s the starkly simple example of her assertion that Jesse Jackson presided over riots in Florida streets in 2000, when the only riots in Florida streets were engineered by the genteel, decorous GOP, or multipage analyses of her factually challenged bestseller, Slander, that litter the internet, she is the nonpareil, ne plus ultra; she is the sine qua non for anyone making this argument. Cheekily or not. —Heck, don’t listen to me, open her book to find any of a number of petards:

In the rush to provide the public with yet more liberal bilge, editors apparently dispense with fact-checking…Books that become publishing scandals by virtue of phony research, invented facts, or apocryphal stories invariably grind political axes for the left. There may be publishing frauds that are apolitical, but it’s hard to think of a single hoax book written by a conservative.

But let’s leave behind for a moment the question of what some on the American right are saying and what it might say about them. Instead, consider these points culled from recent news:

- It is easier to demonstrate a link between the Bush administration and Al Qaeda than it is to demonstrate a link between the Iraqi government and Al Qaeda.

- The Bush administration continues to persecute by any means necessary a war that’s been planned since 1997, instead of acting against the very real and present threat. (Extra credit: John O’Neill and Marion Bowman.)

- And, because I like a trifecta as much as the next guy, there’s the baffling drive to cripple the very government whose stewardship was gifted to the Bush administration by the Supreme Court.

Given that. Given that projection is the attribution of one’s own undesirable traits onto others. Given that a marked propensity for projection can be demonstrated on the part of the right-wing punditocracy in general and Ann Coulter in specific. Give me all of this just for a moment so that I in turn can ask you, an impish smile on my face:

What can we then infer from the title of Coulter’s summer release?

Intellectually superior psychology always trumps defensive emotionality.

Couldn’t have quoted it out of context any better myself, dearie.

Mixed messages,

or, The incoherent text.

They’re not showing those Hallie Kate Eisenberg commercials before the movies anymore, but seeing a flick in a Portland theater hasn’t gotten any better. You pay your $5.25 (because honestly, who pays full price these days?) and then you sit down for a good six to ten minutes of commercials. Before the previews. And after that interminable waiting period where the screen is filled with slides from local low-budget advertisers (and those inane movie trivia squibs from Pepsi [if you live in a Pepsi town] or Coke [if you live in a Coke town]) and an audio feed is run of recently released pop hits, with the names of the artists, albums, and labels carefully enunciated, should you be moved to swing by the Sam Goody on the way to the parking lot.

And the last couple of times I’ve gone, they haven’t shown those Foundation for a Better Life PSAs, either. Which is kind of a shame; they’re slick and smarmy, yes, but still, it’s better to see a big bald biker shamed (a little, and genially) into being nice to a couple of little old ladies than it is to see the long-form brilliance of that ad for the new Volvo SUV.

Of course, even a simple PSA celebrating gratitude (pass it on!) can be more complex than it first appears:

Accompanying the opening strains of “Born to Be Wild” (a countercultural anthem of the late 1960s, prominently featured in 1969’s “Easy Rider”), the video opens with typical MTV-style of quick, staccato cuts. We see first a longhaired biker, and then a series of bikers, from various angles, hopping on their motorcycles, in front of a 60s-style diner, to the opening lyrics of the song (“Head out on the highway, looking for adventure,” etc.) A large, muscular biker, a skinhead who bears more than a passing resemblance to the wrestler “Stone Cold” Steve Austin, finds that his bike has stalled. Frustrated, he hops off the bike, gestures angrily at it, and galumphs to a pay phone, aggressively digging in his jeans for some non-existent change. Concurrently, on the left side of the screen, two small and elderly black women exit the diner and wobble on down the street. They approach the payphone as the lyrics tell the listener to “take the world in a love embrace.” Just then, the biker turns to them, and peevishly announces that the “phone’s taken,” evidently fearing that these elderly black women are in the habit of using public phones. One of the elderly, bespectacled black women looks at him with obvious concern, and diagnosing the situation, offers up some coins, as her voice creaks out the question, “Will this help you?” To the strains of “we were born, born to be wild,” the biker, a bit startled, examines the coins, and takes off his sunglasses. We see his face slope downward and soften. Softly he says “Hey, thanks.” The two women smile, and as they wobble away, he says, “I appreciate it.” As this biker puts the coins into the payphone, the graphics “Gratitude,” and “Pass It On” appear on the screen with the Foundation’s ID, just as the voiceover reiterates the words on the screen, and the name of the sponsor (The Foundation for a Better Life). Apart from the simplistic moral tale, a number of iconic reinscriptions have occurred here. First, both the denotations and connotations of the song, “Born to Be Wild,” and its most famous setting (in Easy Rider) have been flipped on their “heads.” “Easy Rider” chronicles the life and death of two “long-haired” bikers who take LSD with hookers while in a New Orleans graveyard. They also smoke a bit of marijuana, and as drug couriers, are essentially assassinated by rednecks in the segregationist U.S. southland. The main characters played by Peter Fonda (Wyatt “Captain America” Earp) and Dennis Hopper (Billy) function as iconic magnets for overt conflict over the implicit boundaries of “the American Dream” throughout the film, as they ride from Los Angeles to New Orleans, on their way to Mardi Gras. They are not symbols of unity and social harmony.

Likewise, the “biker’s” skinhead appearance in the FBL’s video gives him an “Aryan Nation” patina. As iconic skinhead, it seems very unlikely that elderly black ladies would approach such a figure. Given the decades of hostility between white supremacists and the black population of the US, a more realistic response would have been to quickly pass by the pay phone, saying nothing. Obviously, that’s not what happens in the video. What occurs is a recoding of these icons and histories into a structural-functionalist consensus (over gratitude and all the other common and desirable virtues). In doing so, they well illustrate Gomez-Pena’s claim about the shape of a corporatist multiculturalism that “artificially softens the otherwise sharp edges of cultural difference.” But why? And, why now?

(Of course, the Volvo commercial is in its own way fun to dissect: note the sexual subtexts in each “sighting”: the young son dreams of escape on the Loch Ness monster; the adolescent daughter dreams of a unicorn; the mother dreams of seeing Elvis driving a convertible down a desert highway [which—tangent—makes me think a) of James Dean, not so much Elvis and b) raises (tangentially, yes; those Harley Earl Buick commercials do it much more directly) the perennial question of why on earth car manufacturers try to sell modern cars by hearkening back to older models that were pretty much without exception better looking]; and the father’s dream is rather notably absent—are his dreams not worth commenting on? [Has he been stiffed?] Are we supposed to make the inference that this new Volvo SUV is his dream—thus, on the one hand, backhandedly remarking on the paucity of his imagination [an impractical thing, suited only for impractical people] while suggesting that only his [practical] dreams are deserving of reification? Are the dreams of the presumed norm, those white, middle-class, family-headin’-up men, to be kept private, hidden, safe, unknown? And whether that’s empowering or disempowering depends on context and strategy, of course [and the commercial rather wisely leaves both entirely in the reader’s hands]. —See the fun you can have before they show the trailer for the latest Jim Carrey vehicle?)

But! It’s the context of Regal Cinemas as digital pipeline snarfed up by predatory Native-American-heritage-drillin’ Qwest-ownin’ Bob-Dole’s-hand-shakin’ evil-white-capitalist guy, to be used to pump heavily coded crypto-fascist feel-good agitprop into the eyeballs of millions of captive moviegoers—it’s that context that makes it so terribly funny (to me, at least) that, when we went to go see The Two Towers last month, before the previews, before the ads and the PSAs, while we were finding our seats and they were showing those slides of local advertisers and inane movie trivia, and playing over the speakers snippets of new releases (artists and labels and album titles carefully enunciated, so you can remember them when browsing the aisles at the Barnes & Noble after the show), and right after the latest smooth smooth R&B sensation, they announce their next song is from a Russian pop duo: “All the Things She Said,” by t.A.T.u. (The generic announcer spelled it out: Tee. Ay. Tee. You. Clearly. Carefully. Although I imagine most people will end up calling them “Tatu.”)

And I’m all mixed up

feeling cornered and rushed

They say it’s my fault but I want her so much

Wanna fly her away where the sun and rain

Come in over my face

wash away all the shame

When they stop and stare—don’t worry me

’Cause I’m feeling for her

what she’s feeling for me

I can try to pretend, I can try to forget

But it’s driving me mad, going out of my head!

Russian lolitapop lesbians in their panties. Pass it on.

—I should maybe provide some context.

Volkova Julia Olegovna and Katina Elena Sergeevna were low-level toilers in the Russian youthpop industry, a sort of second-string mirror of the Disney-Orlando nexus that gave us the boy bands and Brtineys of the late ’90s (like those third-world knock-offs of Guess jeans and Star Wars action figures ) when they were plucked from a cattle-call audition to star in the latest creation of former psychiatrist and advertising executive Ivan Shapovalov (a sort of second-string knock-off of Lou Pearlman ): t.A.T.u. (Also: Tatu, Tattoo, t.A.T.y., and Taty. Since the “oo” sound is figured by “y” in Cyrillic. Comes from tattoos, which are hip. Or an abbreviation of “Ta liubit etu,” a rough transliteration of a phrase meaning “She loves her” or “This girl loves that girl” [I’m assuming some sort of slang or dialect; this doesn’t sound much like what little I remember of my Russian would suggest. “Liubit,” yes (“Ya liubliyu tie,” while it looks awful in Romaji, is one of the more beautiful ways in the world to say “I love you.”—With a good dark rich accent, of course), but “ta”? “Etu”? (Brute?)].)

The basic shtick: Yulia and Lena perform in schoolgirl outfits—kilts, blouses, ties; also, incongruous electric blue kneepads—singing emphatically of freedom and escape and not taking it any more and, well, their love for each other. They usually strip off each other’s kilt and blouse and perform some of the more energetic numbers in matching white T-shirts and underwear. (Also, kneepads.) The highlight of each concert is a kiss, which has started riots. (Also: riots when the kiss has been banned.) They started the band when Yulia was 15 and Lena 16. Lena’s now 18; Yulia’s going to turn 17 in February. They’re the biggest pop act ever to come out of Eastern Europe. They’re angling to hit the American market bigtime. Their video is already in rotation at TRL. And music critics are lining up to lament the fall of Western civilization. (The music? Chirpy Europop. Better in Russian than English, but all cheap pop music is vastly improved by not understanding the lyrics, and singing in phonetic English flattens their voices, which are a bit better than not. Also: they “do” a Smiths cover on the American release. “How Soon is Now.” Just so’s you know.) —My God, they’ve even cropped up in blogtopia.

So I think it’s too late to stop them. If you were so inclined.

And you might well be so inclined: there’s a lot not to like here. This is rank exploitation, by any definition of the word. Should you doubt it: take a gander at the photos they’ve shot for Maxim and Jane, for a neat-enough bracketing of the current scope of the newsstand. —Or go for broke with the stuff done for the Russian Maxim. Go: read the reactions that first popped up on MetaFilter back last summer. They aren’t even “real” lesbians, after all. (Though the epistemological implications of that sentence are staggering, to say the least; one could have a field day writing papers on the warring meanings of the word “lesbian” as used within lifestyle squibs written about t.A.T.u.) —The kisses and cuddles are all an act, put on for the stage and the cameras; some denizens of the bulletin boards insist the two girls really hate each other. (Some denizens insist Elton John wants to adopt the girls. Grain of salt and all that.) The thing is, they’re cheerfully, maddeningly upfront about how it’s a put-on. Sort of. “Everybody thinks we are lesbians,” says Lena. “But we just love each other.” (Keeping in mind that this is translated from the Russian, of course, and that leering Ivan Shapovalov, that cigar-smoking svengali, is hovering in the background, controlling everything they say.) There’s also the boyfriends the tabloids write about and the husbands they want to have one of these days.

So: exploitation; objectification; a manufactured pop phenomenon taking on the trappings of marginalized sexuality for edgy thrills; frat boys giggling over photos of schoolgirl lesbians; nymphettes cavorting on stage in their underwear; a synthesized Europop cover of a Smiths song. Ivan Shapovalov is out to make a buck by any means necessary, and Interscope is more than willing to aid and abet him, and Matthew Yglesias should be ashamed for having been taken in.

But a funny thing happens with pop culture, betwixt cup and lip.

Robin Wood is a film critic who talks about the “incoherent text,” a text that says several conflicting things all at once—his seminal example being Taxi Driver, which at once condemns and celebrates Travis “You talkin’ to me?” Bickle, though he did extend the idea, asserting that the incoherent text was the dominant storytelling mode of ’70s cinema, “full of ideological contradictions and conflicts that reproduce existing social confusion and turmoil.” (And now that I’ve set all my pieces on the table, and am about to try to make a pretty shape out of them, can I just digress a moment to point out that I know about Robin Wood because of Buffy? That he’s a Freudian [and anti-American self-hating leftist socialist, to boot] critic with an abiding interest in themes of repression? That Buffy’s tagline this [it is to be hoped final] season is “From beneath you, it devours”? That the principal’s name [wait for it] is Robin Wood? And you remember how Jonathan was killed? And the principal was the guy who, all as-yet unexplained, dragged his body out of the basement of the school around back and buried it? So tell me, you smart people: why the fuck is a character named for a Freudian critic of horror films repressing the evidence of a horrific sacrifice by burying it? Hmm?) —Ahem.

Where was I?

Oh.

Okay: I don’t want to suggest that crypto-fascist PSAs or faux-lesbian lolitapop stars are deliberately, consciously incoherent texts; the good stuff, the art that is more than one thing, that embodies and takes up on all sides the struggles it’s about. But any time there’s a dissonance between what’s said and what’s read, you have incoherence. (Don’t take that too far; given that no one ever reads even the most didactic piece in the manner in which it was intended, one could then state that every text is incoherent. While this might prove a useful point in a cocktail party donnybrook, it renders the term itself useless, critically speaking.)

The dissonance between what the “Pass It On” PSA says on its surface and how its subtext works, and what we can infer of the intent behind it from the circumstances behind its creation and distribution, sets up an interesting enough incoherence that makes for a diverting field of critical play. (Some might call it hypocrisy and move on, but they’re no fun to play with.)

t.A.T.u. is set up by a leering svengali who cynically pulls every last trick out of the books, and outraged critics (who really ought to know better) are all too eager to fall into line and into their scripted roles, damning the whole concept to the horrible fate of selling millions of records. But to insist that the only way to read t.A.T.u. is as exploitation, as a man’s debased idea of teenaged lesbian love, as Europop tarted up with a tawdry underaged striptease, is to deny the readings of hundreds of thousands of online fans who have found something of value—whether it’s an expression of something they feel themselves (faked or not), or of something they know is in the world and want to see reflected in their music and pop culture, or something more basic, more primal (oh, hush): after all, teenagers directly and unapologetically expressing their sexuality (cleanly, simply, shorn of the cartoonish excesses of Britney and Christina—which are, after all, rather clearly not sex, not as we know it)—that’s a gloriously satisfying fuck you in an age which thinks calling students “sluts” is acceptable sex education. (Certainly, it’s the closest thing to genuine rock ’n’ roll rebellion I’ve seen these past few benighted years.)

“And if the young women of Tatu are genuine teen lesbians, their willingness to delve into matters of homosexuality on a public stage could very well be a source of some inspiration to the many other teenage lesbians out there.” Which is what The Star’s critic had to say. “If they’re merely fanciful eye candy for men who dream of a world where women never wear outerwear and routinely drop giggling to the ground for tickle fights, the high-stakes pop market has hit yet another new low.” —And that’s the rub, isn’t it? After all, why on earth can’t they be both? More or less. Here and there. At one and the same time.

It all depends on who’s reading it, and when, and how, and where. Also, why.

Incoherency.

(Yes, but what about how that rebellion is commodified, packaged, and sold? And how faux lesbianism aside, Shapovalov is trafficking in the images and ideas of girls in emotional distress, marginalized; defiant, yes, but unsure, uncertain, confused; above all, girls who need to be protected? —Oh, shut up. It’s getting late.)

Anyway. That’s why I laughed, when t.A.T.u. started chirping about “All the Things She Said,” before a Mormon PSA designed to gently nudge us all back into a kinder, gentler, less confusing, more coherent Golden Age. Mixed messages. Futility is sometimes terribly funny. (And then, of course, we saw part two of The Lord of the Rings: a story of the importance of mercy and the power of redemption set in a world profoundly and irrevocably split between good and evil.)

—At least, that’s part of why I laughed.

Too much woman (for a hen-pecked man).

“What’s the difference between you and Peter Tork?” asks Phil.

“Me?” says me.

“As an example. What’s the difference between you and Peter Tork?”

“I don’t know. What’s the difference?”

“You didn’t date Nico.”

I love it when Phil comes to visit.

We picked him up this morning for a late breakfast and a few hours of general bumming around. The plan, as laid out yesterday, had been to maybe do some record shopping.

“No,” he says, at breakfast. “Scratch that. I blew my budget yesterday. Unless…”

When Phil trails off like that, it’s an invitation to prod him for more. This is always worthwhile. “Yes, Phil?”

“Well, I’m trying to fill in some of the gaps in rock history between, oh, Char Vinnedge and, oh, Chrissy Hynde…”

Jenn and I grin at each other. “Who?” says Jenn. —She’s asking about Char Vinnedge, of course. I mean, if you don’t know from Chrissy Hynde, well, read this and go buy some albums and listen to them and then come back. Not to be snooty or anything. But.

Anyway: Char Vinnedge: as Phil tells it, back in 1964 the Beatles came to America. Vinnedge went to see them in concert and (like most screaming young girl fans) left with the burning desire to form her own band just like them. So she dragooned her sister and a couple of friends into playing the songs she wrote and they called themselves the Luv’d Ones and if they never quote broke out of the Michigan circuit back in the day, we can in this 21st century buy a run of their stuff off Sundazed Records and with the benefit of hindsight note how ahead of their time they were and how Vinnedge was a guitar god of the first water and if we go a bit overboard sometimes, assuring folks they weren’t the puppets of record company executives, they weren’t a marketing gimmick at all, why, that all-girl band really did play their instruments, well, it’s understandable. (We’re frequently reminded the Monkees could play their instruments, after all.) —But the Luv’d Ones are unusual. They were ahead of their time. They blazed a trail, back there in the mid ’60s, for all that it’s gone largely unnoticed.

Rock history, then, from Char Vinnedge to Chrissy Hynde.

“Well,” says Phil, “for one thing, there’s the Joy of Cooking.” And can we stop for a moment and reflect on how fucking cool it is to name an American roots-folk-rock band the Joy of Cooking? “They were formed in the late ’60s, early ’70s, when I think both of them were in their 30s. So they were doing rock songs about housewives being abandoned by their husbands and having nothing to do all day but drink, you know? But they weren’t an all-woman band. They had some guys who would come and play their instruments and keep their mouths shut. And anyway, they aren’t the ones I’m looking for. Not today…”

“Oh?” I say.

“Fanny,” says Phil. “Fanny and Birtha.”

“Fanny,” says Jenn.

“And Birtha,” says Phil. “I’ve got one album by Fanny, but it sucks. Still. It’s an all-woman heavy rock band from like 1971. And Birtha I think put out two albums, and everyone says they’re better than Fanny, but I’ve never seen either one anywhere. So I’m safe. I’m not going to find them. I mean, I blew my music budget yesterday…”

So we pay for breakfast and Jenn heads back to the house to work on the latest page of Dicebox and Phil and I stroll down Hawthorne to Excalibur, where he picks up a 1973 copy of The History of Underground Comics (out of print). “I blew my music budget,” he says. “Not my buying-neat-stuff-on-a-whim budget.” And on our stroll back to the car, we happened to pass Crossroads Music, and since Phil had already blown his music budget and anyway he was not going to find what he was looking for, he was safe, right?

Score: Birtha, by Birtha; Charity Ball and Rock and Roll Survivors, by Fanny; and a copy of Sandinista on vinyl, which isn’t one of the gaps Phil was trying to fill, but is pretty thin on the ground at this moment in history, so.

And so I got to hear Birtha, and I got to hear Fanny, and I think I agree: Birtha’s the better band. The opening track on the album—“Free Spirit”—gets this chugging beat underway that cries out for some Quentin Tarantinoid to dredge it up for a perfectly obscure moment of transcendent pop-culture swagger on film. And if Shele couldn’t quite do the Janis she was trying for (I think it was Shele), well, she hit close enough to not have any regrets, I think. —But I’m perverse: I think I like Fanny better. Of the two albums we heard, I’d be more likely to play Charity Ball than Birtha. More range—no, not quite; more ambition in what they were reaching for, even if they weren’t as successful in pulling it off. It was a more fun album, in some respects. But I want both albums in the house—it was like—okay. There’s the Replacements song, “Alex Chilton,” right, which is one of the best songs ever. And it’s about Alex Chilton, who was the prodigy kid behind Big Star, whom a lot of people who know from music talk about but you don’t hear all that much. So I finally go out and get the CD that has Big Star’s first two albums together, and I play it, and it was—but I need to digress again. Back in high school there was a cool radio station in Chicago whose call letters escape me. Michael Palin, looking for a quick hit of cash, did a couple of rather funny television commercials for them. In one of them, he was inexplicably holding a pizza while informing the viewer that this particular radio station did not play its music over and over and over again from some pre-programmed hit list. Variety, that was the key. A wide spectrum of songs. He looks down at the pizza, and sighs. Holds it up. “And to think,” he says, “This was once ‘Stairway to Heaven’.”

Maybe you had to be there. But: the point: Big Star is pretty squarely in the genre called Classic Rock; it’s what you’d hear on the radio in the upper 90s to the low 100s, I guess, and don’t those stations usually have a morning Zoo? “Aqualung” and Foreigner? You know? Big Star would in style and approach and general sound fit seamlessly into that format. —Except that it isn’t pizza.

And neither is Birtha. And neither is Fanny.

And now I want to hear some Luv’d Ones, too.

“They weren’t the first, though,” says Phil. As if one could ever point to anyone and say, that person, there, that’s the first. As if the category we’re talking about—women rock instrumentalists? Rock bands fronted by women who wanted to front their own rock band?—were anything more than a vague sketch. Fanny and Birtha weren’t the only points (we could maybe hunt around for whatever Bitch put down on tape somewhere) and of course Char Vinnedge wasn’t the first (if you wanted to get silly about it, you could point to maybe Bessie Smith).

But Phil wants to talk about somebody else. “Nope. There was somebody earlier…”

“Who, Phil?”

He grins. “Kathy Marshall, the Queen of the Surf Guitar. She was 13 years old. She played a lot with Eddie and the Showmen and blew Dick Dale off the stage. And guess how many recordings she has.”

I shrug. Phil holds up his thumb and his forefinger and makes a circle with them.

“There’s a couple of acetates somewhere of two songs written for her that nobody’s pressed,” he says. “That, and maybe six pages of photos of this 13-year-old girl in a cute little dress with a Fender Stratocaster in the Encyclopedia of Surf Guitar. She apparently lives in Orange County these days. Had a couple of kids. She’s what, 52?”

And then we talked about whether one can categorically state that Death is a character in every Coen Brothers movie (I can’t find it in The Big Lebowski and I’m not entirely certain about The Man Who Wasn’t There) and what you’d maybe put on a mix tape that begins with “Mink Car” and ends with “All Tomorrow’s Parties.”

“Hey,” says Phil. “What’s the difference between you and Peter Tork?”

I love it when he comes to visit.

Ludafisk.

If you give a man a Fisk, you’re an insufferable asshole, but if you teach a man to Fisk, you’ve created a whole new asshole.

I suppose this was the immediate impetus, but I’m shall we say reluctant to ascribe to the piece any recognition beyond that which it’s already gotten, and anyway, it’s merely a catalyst which has set off a chain reaction prompting me to try and synthesize some half-formed, vague ideas kicked loose by Barry’s discussion thread on pornography and some (very) recent reading on Russian magic and some speculatin’ on the nature of Gödel’s Theorem, which I’ll doubtless take as far out of context as poor old Schrödinger’s Cat . (Someone keep Professor Hawking away from the gun cabinet, please?)

Webster’s defines Fisking as—well, no, it doesn’t, not yet. But definitions are out there; most seem to cite the Volokh Conspiracy, so let’s do the same (by way of the Neo-libertarian News Portal):

The term refers to Robert Fisk, a journalist who wrote some rather foolish anti-war stuff, and who in particular wrote a story in which he (1) recounted how he was beaten by some anti-American Afghan refugees, and (2) thought they were morally right for doing so. Hence many pro-war blogs — most famously, InstaPundit—often use the term “Fisking” figuratively to mean a thorough and forceful verbal beating of an anti-war, possibly anti-American, commentator who has richly earned this figurative beating through his words. Good Fisking tends to be (or at least aim[s] to be) quite logical, and often quotes the other article in detail, interspersing criticisms with the original article’s text.

A thorough, forceful (if figurative) beating, then, that tends to or at least aims to be logical, administered to someone for something they said. And I like my humor neck-snappingly bleak, so it is with a small grim smile that I appreciate the aptness of taking one’s inspiration from an account of a thorough, forceful, illogical beating administered by an angry mob to someone erroneously assumed to be an agent or a symbol of that which is evil or bad or harmful—or at the very least of that which is pissing them off that particular day. —And, like Fisk, I am not without my sympathy. Even as I scratch my head at trying to parse the “logic” in refuting a citation of Gandhi’s life’s work by pointing out the man was assassinated. (“And look what happened to him.” “Oh! Jolly good show! ’it ’im again! ’it ’im again!”)

But I come not to Fisk a Fisking. —Not because I think Fisking is wrong, no. Not because I curl my lip in a disdainful sneer at figurative beatings, or recoil from the taste of blood on my rhetorical jackboots. Nor because I’m tired, and think it’s a futile endeavor, akin to Canute spitting into the oncoming tide—I am, and I do, but that’s not why I’m not Fisking a Fisking today. No.

It’s because it’s so damned easy.

My Christmas present to myself this year was The Bathhouse at Midnight, W.F. Ryan’s monumentally descriptive survey of (as the subtitle puts it) magic in Russia. In his introduction, he lays out the intended scope of the book (which, as noted, is monumental), discussing the problems one encounters when one sets out to write about the history of magic in Russia, and one must figure out what it is one means when one says “history,” “magic,” and “Russia.” How does one account for the differences between written and oral traditions—especially when the border is as permeable as it is in Russian history? What bits of all those many and varied regions stretching across 11 time zones that we (or some of us) have at one point or another called “Russia” do you include, and what do you leave out? What is magic? How do you know it when you see it? How can you differentiate it from assumptions of divine intervention, or folkloric tradition, or religious ceremony? (Do you need such differentiations in the first place?) —The most interesting of these definitional problems is figuring out what magic is, of course, or at least coming to a vague agreement as to the particulars of what we’ll call magic for the course of the book. Ryan never quite comes out and offers a firm definition of his own (beyond the general impression that he’ll be more inclusive than not—a fine and worthy goal, in this case), but he does summarize some interesting definitions along the way: Magic is an alternative to religion, the other side of its coin, a corruption of it, parasitic to religion, a deviation from spiritual or social norms, or (charitably) a semiotic system of oppositions to religion. That form of religious deviance whereby individual or social goals are sought by means alternate to those normally sanctioned by the dominant religious institution. Magic’s goals are overwhelmingly the expression of personal desires for sex, power, wealth, revenge, relief from sickness or protection from harm; religions usually have social, ethical, spiritual, and numinous aspects that transcend individual ambition. But as Ryan puts it (and I’ll quote directly now, rather than tightly paraphrase): “Most attempts to come to terms with the sameness or distinctness of concepts of magic and religion suffer to some extent… almost all can be made to fit the evidence at most points, and almost all break down at some points in specific cases.” Each definition is a useful enough tool in and of itself, for doing what it is it does, but each breaks down somewhere or another. The tool is to be used when needed and set aside when not; definitions should always (strive to) be descriptive, not prescriptive. The map is not the thing mapped. This is important to keep in mind, because, to quote Gábor Klaniczay (and to drag this digression back onto the ostensible topic of Fisking):

The wide array of theoretical explanatory tools and comparative sets stands in puzzling contrast to the ease with which each general proposition can be contradicted.

Call it Klaniczay’s Corollary to Gödel’s Theorem and keep it in mind; we’re off on another digression.

—Samuel Delany has written (most notably in “Politics of Paraliterary Criticism” in Shorter Views: Queer Thoughts and the Politics of the Paraliterary, and thank God John still has my copy, or I’d start quoting at length and we’d never get out of here) that one of the central problems with sympathetic attempts to seriously critique paraliterary stuff like comics or SF is that they almost always start with an attempt to define the thing to be critiqued. Delany’s point is that genres are impossible to define, because they are social constructs, highly permeable categories highly fluid both from day to day and person to person. One can never delineate with any degree of precision the necessary and sufficient conditions that make SF SF, or comics comics; therefore, attempting to define them is futile from the start. Also, it lends a déclassé air of pseudo-science to one’s criticism, as if one has such a distrust of one’s material that one must appeal to a nominally neutral definition as an argument from authority. (Webster’s defines SF as…) So quit stinkin’ up the joint, kid; you’re embarrassing me.

Which is not to say I agree wholly with Delany, or that there’s never a need for definitional thinking. Criticism can be cheekily likened to one of those blind folks with the elephant discoursing at length about what it is they’ve experienced, the immense fan-like quality of it (or the peculiarly prehensile, ropey nature, or the way it calls to mind thick, gnarled tree trunks), how that quality compares with what Foucault says about how it’s really a wall, and the thoughts set in motion by contemplating the differences and similarities of the ways we each perceive this thing we call “elephant.” It helps in this circumstance to articulate what you think you’ve experienced, and how, and why; it helps to say right off the bat what it is you think an “elephant” is. —But to mistake this articulation for a definition is to mistake a description for a prescription, a tool for a law, the map for the thing mapped. It is to believe you’re really talking about a fan, a rope, a tree trunk, a wall, and to forget we’re all trying to figure out what this thing called “elephant” is.

There’s another reason to eschew the definition in criticism (or polemicism): because definitions are by nature imperfect, theoretical explanatory tools that can with puzzling ease be contradicted in one or another of their particulars, because for any given axiomatic system there exists propositions that are either undecidable, or the axiomatic system itself is incomplete, well, it’s all too easy to poke holes in definitions. And it’s all too easy to mistake poking a hole in a definition for refuting someone’s argument; to say, “The tool you made that house with is imperfect, therefore the house is not worth my consideration.” (Which, no, is not what Audre Lorde meant.) —And even if the debate is entered into in good fun and good faith, it’s all too easy to get sidetracked arguing about the words one chooses to define the thing instead of coming to grips with the thing itself.

And Fisking is little more than poking holes in someone else’s definitions.

Each statement of the anti-war, anti-American speech to be Fisked is parsed as if it were a definition: of the speakers’ credo, his or her intentions, worldview, as a statement of what anti-war anti-Americans in general think. Any contradiction that can then be pulled from what the Fisker takes to be that credo or worldview, or those intentions, or any action from anyone counted as anti-war or anti-American, is then held aloft, trumpeted, crowed over as a critical flaw in the thinking of one’s target. See? A contradiction! See? The tool is imperfect! See? We don’t have to pay any attention to the house! —When in doubt, point out that Gandhi practiced non-violence. So did Martin Luther King, Jr. And they both got assassinated! See? Quod erat fuckin’ demonstrandum.

’it ’im again.

When we talk about—anything, at length, our own experiences, what we think those mean, morally, ethically, politically, critically, when we talk about the camps of feminism or vampire slaying television programs or whether or not we should go to Iraq to demonstrate a commitment to something as ridiculous as peace and as ludicrous as respect for human life, over beers at the bar or in our blogs or in peer-reviewed journals, we are, in a sense, describing our piece of the elephant. Comparing it with what other people have said about that elephant. And we can keep in mind the shortcomings of definitions (or decide that what I’ve laid out here is utter hogwash), but we can’t help but speak in them; and whenever we try to define what it is we mean when we talk about the elephant (whether it’s the one in the living room or the one that just did the loop-the-loop under the big top), we can’t help but define ourselves. Debate based on respect does its best to reach past those definitions, to look from the tools to the thing being built with them, to leap from the map to the thing mapped. It may miss, it may disagree, it may get it wrong, but it makes the attempt. And this takes work. It doesn’t come easy. (That’s why it’s usually a mark of respect.)

On the other hand, anyone at all can trumpet a contradiction. Anyone at all can complain about a tool. Anyone at all can kick, can lay into someone with the boots and fists of an angry mob, can crack open a cheek with a thrown rock. —Whether they aimed it logically or not.

Anyone can Fisk.

And that’s why I don’t. It’s déclassé.

An interesting wrinkle,<br /> <em>or,</em> Again with the posse.

So Norah Vincent riffs on an old Jackson Browne lyric uncredited and Charles Pierce emails James Capozzolla pointing this out and Capozzolla decides to rib Vincent about it and posts Pierce’s email in its entirety with the headline or rather subhead “Norah Vincent: Jackson Browne Fan—And Plagiarist?” and now Vincent is tut-tutting over the outrageous slings and arrows that are let fly at established Fourth Estaters from the unwashed, the unpoliced, the unshackled. (Yes, I know blogtopia is self-policed by a fairly neat and effective smart-mob mechanism. But “self-washed, self-policed, self-shackled” just doesn’t have the same ring.)

—For the record, and not that anyone asked: I don’t think what Vincent did to Jackson Browne was plagiarism. Then, I live for the oddball allusion and the kick that the echo of a half-remembered snippet of something else can add to a piece. Nothing new under the sun and Fair Use and Devil take the hindmost or hang the consequences or whatever. Capozzolla was if a wee bit disingenuous still quite right to put that question mark after “Plagiarist?” But! Were someone to tag me for, oh, I dunno, stealing a parenthetical aside from Delany (it was just sitting there, honest, so plump and digressive), well, I’d cheerfully own up to it. And on we go to the next. —Not obsessively stew over it with conflicting rationales for a couple of days and then drag it back into the spotlight when online Wall Street Journal content is successfully held liable for libel in Australia. Dirty pool, that is, and we’re not even taking into account her refusal thus far to name those she accuses of the smearage.

So Capozzolla is right to take the incident apart in a fine and mighty dudgeon, and Vincent’s editor would do well to maybe take his phone calls on the matter.

(Psst. Mr. Capozzolla? Not to get all pedantic or nothin’, but it’s never “the hoi polloi.” Just “hoi polloi.” Verb. sap. and all. Not that anyone asked. But.)

Fort Disconnect.

“Eighty-seven thousand dollars?” says Valerie. She has the office next door and two kids and a house out over the hills and a husband who also works full-time. She’s talking about this. (Really, it’s $87,510. If you live in Virginia, the state government will pick up an additional $3,937.95 in sales tax. There’s no shipping and handling, but it’ll take 12 weeks or so to make arrangements with the artisan to have it built on your property. So you’ve pretty much missed the holiday deadline, if you were hoping otherwise.) And before we get too much further, I should probably make it clear that I have nothing against said artisan or people who have the wherewithal to pay $2,870 for a credenza or $8,980 for a trundle bed or $15,492.50 for a toy Range Rover or even people who spend more than my good friend Amy blew on a house for a backyard fort. (Amy works full-time for the county. Her housemate and swiggee is getting a law practice off the ground. No kids, but two cats, and we all know how cats are.) And I don’t have anything against the people who are trying to make a buck off selling the most extraordinary children’s furnishings in the world. (Aside from perhaps a lingering resentment at yet another attempt to provide “an unparalleled on-line shopping experience.”) —I’m as eat-the-rich as the next guy, but let’s face it: when you’re projecting $3 million in annual sales, you’re not moving too many toy Range Rovers or backyard fortilaces or probably not even $2,100 Silver Stream prams. Those are showpieces, wowpieces, beautiful chimeræ that you can order, yeah, sure, but are really just there to build buzz and get the punters in the door, lending a burnish of class and elegance (with a soupçon of crass consumerism) so they feel a sympathetic shiver as they pony up for $136 lamps and $30 backpacks and $60 rugs. So: no potshots at Posh Tots.

I have an altogether other purpose.

Go back to Posh Tot’s front page and note with what pride they spotlight the items ordered through them that grace the baby nook of Rachel and Ross’s apartment on Friends. The Black Toile Adult Glider, the Classic Changing Chest, the Retro Crib, the Silver Cross Ascot Stroller, the (handpainted) Princess Wallhanging, the Sir Lance-a-Trot, Jr. Ruminate for a moment on this: an untenured professor of pæleontology and a middle manager in purchasing for a large clothing concern—or is she still with Ralph Lauren? I don’t follow the show that religiously—these two middle class low-rent bobos are spending $3,598 on six classy, high-ticket items for baby Emma. (Even with the rent on their spacious West Village apartment.)

I’m a project manager for a small legal database firm these days (apparently, I’m also something of a paralegal now, or something); I also freelance as a designer and a writer (I swear, Brett, I’m working on it! Honest!). The Spouse is in addition to being a world-renowned cartoonist (and you know what that pays) is a production designer for an industrial design firm. We have two cats and too much house. We’re middle class low-rent bobos, and when people ask us these days when we’re going to have a kid we kind of shrug and say well, we’re no longer trying not to. We’re not taking temperatures and eyeing calendars and scheduling nookie, but we’ve given it some thought and crunched some numbers and shrugged and said we can do it, if. It won’t be a drunken accident that catches us utterly by surprise and totally throws our lives and finances out of whack for the entertainment of millions of viewers each week.

Even so, I gotta tell you: no way in hell can we even begin to think of dropping $3,598 on a stroller and a rocking horse and a toile glider and a crib and a changing chest and a handpainted original one-of-a-kind wallhanging.

(Of course, Rachel is in purchasing. Maybe she cut a deal.)

We live much better on TV and in the movies than we do in real life. Delany made a point somewhere or other that I’d quote if I hadn’t loaned my copy of Shorter Views to John that almost all forms of storytelling deriving from the 19th century European tradition (I’m on a limb on that on; I’m remembering the vague boundaries of the class he referred to, and not how he articulated it) take great if unconscious pains to make the protagonist’s class and level of income at least vaguely clear within the first few pages. (Try it out yourself: pick up a book in any genre and watch for the telltale clues. It’s interesting. Now try to imagine telling a story that doesn’t.) —In television, and in the movies, it’s more insidious; the narrative clues of job and responsibility and finances are divorced from their visual cues, dissolved in a general haze of meticulous art direction and product placement. (Think of all the offices on TV workplace sitcoms, which look like the net bubble never burst with their exposed brickwork and Aeron chairs and iMacs—hell, remember the G4 Cube? There were more of those on TV shows than ever actually got sold, I think.) It’s a false image, an eidolon, a fevre dream that can’t stand up to the real: a haze of upper middle class accoutrements with no clear accounting of how they were acquired (we got that easy chair and the sleeper sofa as an apartment warming gift from Jenn’s mother, who anyway wanted somewhere to sleep when she visited us; those bookshelves—the two black ones we bought on sale at Office Depot, but the other two we got in the “divorce” from the household, after carting them around Massachusetts and across the country; the TV set is almost 20 years old; the Fiestaware we registered for our wedding, and Jenn’s grandmother got us most of it; the masks there on the wall were a gift from my parents; the brass table was $20 at a yardsale, helluva find); workplace comedies filled with people whose home lives we never see—where they spend the money they make, or how (or how much), though they always have choice clothes; utter disconnections between the jobs they nominally hold and the wacky situations their impulsive purchases land them in (that untenured professor of pæleontology snapping up an apothecary’s table at Pottery Barn, say). It’s a different world, a disjointed world, and when a show takes a step out of it—even a tiny one—it’s news, it’s a hook, it’s Roseanne or Drew Carey and not much else. (Okay. Malcolm in the Middle.)

But there’s reasons for this and there’s escapism and people aren’t blind sheep working themselves into an early grave for material comforts that will never be enough—they are, but that’s not really where I’m trying to go with this, either, any more than the eat the rich bit. It’s that image of another world, it’s the glass screen between them that I want you to keep in mind. Because when the folks inside the Beltway say that Rep. Marcy Kaptur (D-Ohio) is from another world, I think it’s because they’re in the mediated one. The one where you can buy apothecary’s tables on a whim and $600 bed linens for your 6-year-old daughter, no sweat. It’s not so much thinking that everyone is rich as it is having trouble imagining what not being rich looks like and feels like. Those $12,000 per annum lucky duckies have everything they could ever need, right? They look so happy on TV…

And Kaptur, of course, is from ours. We are the other world.

(Oh, hell. What am I saying? Of course it’s fucking obscene to spend $87,000 on a backyard fort. Jesus. Eighty-seven thousand dollars. Off with their heads.)

Kid detectives. Also, how magic works. (Really.)

Jenn wasn’t feeling well, so I went to Johnzo and Victoria’s by myself. And since for a variety of reasons I wasn’t feeling like engaging in another round of sartorial combat with Mr. Snead (among them: I’d been painting a bathroom and trying to figure out how to build a wall all day; I didn’t feel like a tie; and anyway, I’d just worn my green three-piece to an office party the night before), I decided to dress down: jeans, white shirt, yellow sweater, black Chuck Taylors. Encyclopedia Brown, I decided, looking at myself in the mirror. Twenty years later, that is, and mumblety-mumble pounds heavier, and while I’d like to imagine ol’ Leroy’d grow up to look devilish in the right light with a dapper Van Dyke, the indications are not favorable. —Also, I don’t wear glasses.

Anyway, because I was thinking of myself as Encyclopedia Brown, twenty years later, the pear brandy sipped from a coffee cup seemed that much the sweeter, somehow. The Veggie Booty that much the spicier. It was with an edgy, naughty glee that I larded my sociopolitical rants with unexpectedly crude sexualized metaphor. (Though I rather imagine ol’ Leroy’d ascribe to more of a get-by-on-your-own-merits winner-take-all I-got-mine-screw-you zero-sum libertarianism, rather than [say] tendencies toward Bakuninist anarcho-syndicalism, but one can muse. Regardless, he’d be more willing than I was to cut George Will some slack. Because of the whole baseball thing.) And there was something deliciously wicked about nipping out to score some cloves, even if they were filtertips, and even if it did take me three matches to get one of the damn things lit. —I palmed the matches all the way back to the party, where I threw them tidily away in a dumpster. My two Chuck Taylors, it seems, were still goody.

But what the whole Encyclopedia Brown thing ended up putting me in mind of was Josie.

Josie Has a Secret is maybe my favorite thing over at Kristen Brennan’s shrine to go-go late ’90s hyperactive possibilities. It’s squarely in the tradition of the kid detective, with the puzzle in each chapter whose secrets are revealed at the ever-important back of the book. But unlike Encyclopedia Brown and Sally Kimball, the Dragnet of the kid detective set, Josie and Darla kick it up a little on the amoral, wicked side—more like the Great Brain, say (and those with a better memory for Fitzgerald’s books than me are hereby invited to open up the Wikipedia entry). —Josie and Darla are, after all, not detectives, but magicians (Penn & Teller, that is, and not Harry & Hermione). That’s what makes the book special.

For one thing—toying with magic whether staged or otherwise (?) takes us one big step closer to the thing detective fiction is “really” about. For another, staging the puzzles in each chapter around classic magic tricks that are revealed in the back of the book encourages critical thinking in a more (I think) successful way than pummelling kids through trivia (Encyclopedia Brown knows there’s no Q on the telephone dial, and that the Confederates would never have called it the First Battle of Bull Run until after the Second)—you’re learning the bare bones of pranks you can pull on your friends, after all.

But most importantly: Josie manages to pull off its debunkeries with grace and charm, never stooping to the acidly dismissive sarcasm that Randi and his ilk are all-too prone to fall prey to. It’s a heartening display of intelligence and generosity of spirit in a field that sees all too little of either. (Where the fuck are the sequels, already?)

—Plus, illustrations by Kris Dresen. How can you lose?