Even if you are not a bear, or have no interest in invading Sicily.

There are, I feel, two important morals to be drawn from The Bears’ Famous Invasion of Sicily, by Dino Buzzati. The first, from the prologue, is as follows:

THE WEREWOLF. A third monster. It is possible that he may not appear in our story. In fact, as far as we know he has never appeared anywhere, but one never knows. He might suddenly appear from one moment to the next, and then how foolish we should look for not having mentioned him.

The second, from Lemony Snicket’s rather phoned-in study guide, which, all told, is not nearly so indispensable as the author’s lovely Tolkienesque cartoons:

QUESTIONS YOU MAY FIND INTERESTING:

When the boars arrive, King Leander and Professor Ambrose have completely different reactions. The King draws his sword and cries, “Let us die like gallant soldiers!” The Professor begs, “And what about me? What about me?” Which reaction do you admire more? Keep in mind that the Professor ends up saving everyone’s life.

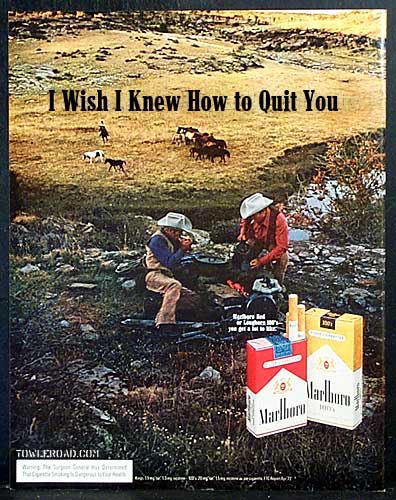

An article of pinnacle stupidity.

I mean, I knew their sense of self was weak; when your character is based so strongly on hate the Other, you’ve got nothing to fall back on for yourself. When that Other is inextricably defined by sexuality and desire, those deep, anarchic, inarticulable forces we must control to control ourselves, then a religion of peace and love and forgiveness can be turned on its head, reduced to nothing more than hate the gay. —It helps to explain why their encomiums to Dear Leader are so comically fellatial, yes, but careful; it also explains why we find it so funny to refer to them as “Assmissile.” There’s two edges on that blade.

So I knew, yes, but dear Lord in heaven and all His little fishes below, I swear I had no idea what a deep and gnawing, rotten and terrifying, Echthroi-howling hole it was inside them, until now—

It is cognitively and nationally dissonant to propose on one hand the advancement of the homosexualization of your most identified national folk icon and simultaneously bluster with the impending force of a war to defend that same civilization. The homosexualization of your most revered masculinity is the cheapest and stupidest shot you can take at the survival of your own culture and it is really inappropriately timed when you are facing, from threats abroad, the most substantial existential peril the nation has ever known. You can’t fight Islamism with gay cowboys.

Oh God, if You are up there, please. Hurry down the Rapture. We’ll get so much more done with them all out of the way. —Via the Poor Man.

A fitter and generally a more effectual punishment.

We were at a restaurant somewhere in Shaker Heights and laughing over this absurd remark or that when he leaned back in his chair and jumped the conversational tracks. “I’ve got one,” he said, an evil glint in his eye. “How does every joke about black people begin?”

Which pretty much stopped the laughter dead. Thing was, see, he wasn’t known for this sort of joke. At all. Thing is, though, how well do you ever really know someone? —Final scheme, and all that.

“Okay,” said someone, after a bit too long. “How?”

And he rested his elbows on the table, looked ostentatiously over his left shoulder, ostentatiously over his right, and then leaned forward, mouth open as if he were about to speak.

We got it.

Would that some guardians of our discourse had the shrunken, shriveled enlightenment of the butts of that particular joke.

It takes a heap of licks to strike a nail in the dark.

From Michael Schwartz at Mother Jones to Body and Soul to me to you:

Here is the Times account of what happened in the small town of Baiji, 150 miles north of Baghdad, on January 3, based on interviews with various unidentified “American officials”:

A pilotless reconnaissance aircraft detected three men planting a roadside bomb about 9 p.m. The men “dug a hole following the common pattern of roadside bomb emplacement,” the military said in a statement. “The individuals were assessed as posing a threat to Iraqi civilians and coalition forces, and the location of the three men was relayed to close air support pilots.”

The men were tracked from the road site to a building nearby, which was then bombed with “precision guided munitions,” the military said. The statement did not say whether a roadside bomb was later found at the site. An additional military statement said Navy F-14’s had “strafed the target with 100 cannon rounds” and dropped one bomb.

Crucial to this report is the phrase “precision guided munitions,” an affirmation that US forces used technology less likely than older munitions to accidentally hit the wrong target. It is this precision that allows us to glimpse the callous brutality of American military strategy in Iraq.

The target was a “building nearby,” identified by a drone aircraft as an enemy hiding place. According to eyewitness reports given to the Washington Post, the attack effectively demolished the building, and damaged six surrounding buildings. While in a perfect world, the surrounding buildings would have been unharmed, the reported amount of human damage in them (two people injured) suggests that, in this case at least, the claims of “precision” were at least fairly accurate.

The problem arises with what happened inside the targeted building, a house inhabited by a large Iraqi family. Piecing together the testimony of local residents, the Times reporter concluded that fourteen members of the family were in the house at the time of the attack and nine were killed. The Washington Post, which reported twelve killed, offered a chilling description of the scene:

“The dead included women and children whose bodies were recovered in the nightclothes and blankets in which they had apparently been sleeping. A Washington Post special correspondent watched as the corpses of three women and three boys who appeared to be younger than 10 were removed Tuesday from the house.”

Because in this case—unlike in so many others in which American air power utilizes “precisely guided munitions”—there was on-the-spot reporting for an American newspaper, the US military command was required to explain these casualties. Without conceding that the deaths actually occurred, Lt. Col. Barry Johnson, director of the Coalition Press Information Center in Baghdad, commented: “We continue to see terrorists and insurgents using civilians in an attempt to shield themselves.”

Notice that Lt. Col. Johnson (while not admitting that civilians had actually died) did assert US policy: If suspected guerrillas use any building as a refuge, a full-scale attack on that structure is justified, even if the insurgents attempt to use civilians to “shield themselves.” These are, in other words, essential US rules of engagement. The attack should be “precise” only in the sense that planes and/or helicopter gunships should seek as best they can to avoid demolishing surrounding structures. Put another way, it is more important to stop the insurgents than protect the innocent.

And notice that the military, single-mindedly determined to kill or capture the insurgents, cannot stop to allow for the evacuation of civilians either. Any delay might let the insurgents escape, either disguised as civilians or through windows, backdoors, cellars, or any of the other obvious escape routes urban guerrillas might take. Any attack must be quickly organized and—if possible—unexpected.

update— And then I wake up to this:

Pakistan on Saturday condemned a purported CIA airstrike on a border village that officials said unsuccessfully targeted al-Qaida’s second-in-command, and said it was protesting to the U.S. Embassy over the attack that killed at least 17 people.

Thousands of local tribesmen, chanting “God is Great,” demonstrated against the attack, claiming the victims were local villagers without terrorist links and had never hosted Ayman al-Zawahri.

Two senior Pakistani officials told The Associated Press that the CIA acted on incorrect information in launching the attack early Friday in the northwestern village of Damadola, near the Afghan border.

Citing unidentified American intelligence officials, U.S. news networks reported that CIA-operated Predator drone aircraft carried out the missile strike because al-Zawahri, Osama bin Laden’s top lieutenant, was thought to be at a compound in the village or about to arrive.

“Their information was wrong, and our investigations conclude that they acted on a false information,” said a senior Pakistani intelligence official with direct knowledge of Pakistan’s investigations into the attack.

The anvil lasts longer than the hammer.

A sideline, an hors d’oeuvres, a carnival bark; but one takes one’s hammers where one can find them:

The public esteem of the profession of arms is at a rather low ebb just now—at least in the United States. The Soviet Union retains the pomp and ceremony of military glory, and the office class is highly regarded, if not by the public (who can know the true feelings of Soviet citizens?) then at least by the rulers of the Kremlin. Nor did the intellectuals always despise soldiers in the United States. Many of the very universities which delight in making mock of uniforms were endowed by land grants and were founded in the expectation that they would train officers for the state militia. It has not been all that many years since US combat troops were routinely expected to take part in parades; when soldiers were proud to wear the uniform off post, and when my uniform was sufficient for free entry into movie houses, the New York Museum of Modern Art, the New York Ballet, and as I recall the Met (as well as to other establishments catering to less cultural needs of the soldier).

Jerry Pournelle, ladies and gentlemen, piping up from 1979 to remind us that even if the ROTC wasn’t really in danger when Alito joined CAP, well, that doesn’t so much matter; we have always already been hating the military more. —That’s from “Mercenaries and Military Virtue,” his introduction to David Drake’s Hammer’s Slammers collection; therein we find the celebrated story “Hangman.” Take up your copies and turn with me now to page 184 of the Baen Books 1987 paperback edition:

“Never been shot in the head myself, Captain, but I can see it might shake a fellow, yeah.” Jenne let the whine of the fans stand for a moment as the only further comment while he decided whether he would go on. Then he said, “Captain, for about a week after I first saw action I meant to get out of the Slammers, even if I had to sweep floors on Curwin for the rest of my life. Finally I decided I’d stick it. I didn’t like the… rules of the game, but I could learn to play by them.

“And I did. And one rule is, that you get to be as good as you can at killing the people Colonel Hammer wants killed. Yeah, I’m proud about that one just now. It was a tough snap shot and I made it. I don’t care why we’re on Kobold or who brought us here. But I know I’m supposed to kill anybody who shoots at us, and I will.”

“Well, I’m glad you did,” Pritchard said evenly as he looked the sergeant in the eyes. “You pretty well saved things from getting out of hand by the way you reacted.”

As if he had not heard his captain, Jenne went on, “I was afraid if I stayed in the Slammers I’d turn into an animal, like the dogs we trained back home to kill rats in the quarries. And I was right. But it’s the way I am now, so I don’t seem to mind.”

Hammer? Anvil? —Context amongst yourselves.

God, grant me the Serenity—

Some interesting musings on class, gender, sex, and the movie of that name.

Koan.

Kyogen Osho said, it is like a man up in a tree hanging from a branch by his mouth. His hands grasp no bough. His feet rest on no limb. Someone appears under the tree and asks him, what is the meaning of Bodhidharma’s coming from the west? If he does not answer, he fails to respond to the question. If he does answer he will lose his life. What would you do in such a situation?

It’s not that an oleaginously pompous third-rater has from a wrought-iron throne on a cedar deck proclaimed me and mine and half the country about him as traitors. That shit—that particular shit—that’s fuckin’ hilarious. What it is is that a couple of oriflammes of our perniciously liberal media have nevertheless in spite of or rather because have chosen this overcompensating twerp and his cohorts as the best our nascent medium had to offer, this past year.

Go crawl back into your hole, you stupid left-wing shithead. And don’t bother us anymore. You have to have an IQ over 50 to correspond with us. You don’t qualify, you stupid shit.

With TIME, I suppose, they could be telling themselves it’s “Blogger of the Year,” you know, like “Person of the Year,” it’s not a mark of respect or who was the best or anything like that, just who had the most impact, like how we picked Hitler and Khomeini. Yeah. That’s the ticket. —But what the fuck is The Week’s excuse?

(Hey, did you read that nutty stuff over at Powerline today? And every day? Here’s my advice. When you find yourself reading something by Hindrocket, some rant about how irrational and traitorous the left is, or the MSM; just sort of pretend you are reading a Spider-Man comic, and Hindrocket is J. Jonah Jameson yelling at Betty Brant, or Robbie. Or Peter. About Spider-Man. Because why does he hate on Spidey so? Spidey is so obviously not a menace. He’s good. It’s too bad we all know who Atrios is now. Otherwise we could imagine: what if Atrios is really, like, Hindrocket’s secretary? I realize it is really a quite serious matter than the right-wingers have gone around the bend and apparently aren’t coming back. Still, you’ve got to find a way to read their stuff with a sunny heart.)

“Am I saying we can all just get along if we all just cut the nonsense and admit we are a nation of pragmatic liberals and Hartz was right?” says John Holbo. “No, but I pretty much agree with what Timothy Burke says in this post. Count me in as a liberal sack of garbage.” —Which confuses me: John’s style, after all—while sometimes perhaps a tad too comfortable for the afflicted—is nonetheless an arrow fit for the quiver the Happy Tutor seeks to fill. I would not call it faux naïveté, but there’s a wicked glee hiding under his sunny heart, one that takes no small delight in walking you through the follies of others. Far too generous and charitable to ever be called Fisking, but it’s precisely that charity and generosity that enable it to do what it does.

But that’s actually why the Happy Tutor wouldn’t tell Holbo to ankle it off the ramparts, and what’s actually puzzling me is why Holbo—whose reaction to David Horowitz’ “Frozen Limit of Silly” is to head out on the ice and land a very creditable hit—why he would align himself nominally with Burke’s earnest liberal tribunes; nominally against the Tutor’s wetworking hockey hitters. —Then again, I’m puzzled by the fact that I, too, agree with Burke: I also want to grab the Tutor’s essay by the lapels and yell, “What’s your great idea, motherfucker?” (“Creating a dialectical set of traps for the unwary reader,” yes, I know. But who’s the unwary reader, dammit? Who?) —Of course, Burke says “I write [as a liberal sack of garbage] because the only way to win a rigged game is to play fair and hope that the onlookers will eventually notice who cheats and who does not,” and I want to grab him by the lapels and yell, “Onlookers? For the love of God, man, what onlookers?” and the whole mess dissolves into another kabuki war of cod-liberal and cod-leftist, which I don’t think was ever anyone’s intent.

I think sometimes the reason we’re so good at circular firing squads is that the only readers we’ve got are ourselves, and you always end up playing to your audience. (Is it pomo cul-de-saccery to note that Gomer Pyle’s as much a rôle as Happy Tutor? Probably, but it’s no less true.) —Meanwhile, the oleaginous pontificies yell at nothing but the voices in their own heads, taking potshots at their puppetuses of the left that somehow still get scored against us. But how? By whom? Who’s onlooking? Who’s reading? —How do we knock the scales from someone else’s eyes?

Even if your eloquence flows like a river, it is of no avail. Though you can expound the whole of Buddhist literature, it is of no use. If you solve this problem, you will give life to the way that has been dead until this moment and destroy the way that has been alive up to now. Otherwise you must wait for Maitreya Buddha and ask him.

It’s just a war of Whig on Whig, says John. A family squabble. Not so fast, says Bob McManus, spitting out some numbers from the latest naked attempt to shift the tax burden off the rich onto the rest of us. Yes, yes, I know, says John. (“I realize it is really a quite serious matter than the right-wingers have gone around the bend and apparently aren’t coming back,” he says. “Am I saying we can all just get along if we all just cut the nonsense and admit we are a nation of pragmatic liberals and Hartz was right?”) But without a sense of historical perspective, of moral perspective, you can’t leap into battle with a sunny heart. —But how can you laugh at a secret note in your permanent record? asks Roz, and maybe she’s grinning as she asks, but it’s a grim little grin (and the Happy Tutor, after all, is looking over a cold chain of law already forged that could easily lead from Horowitz’ frozen limit of silly to a long, long stint in jail). And maybe we can all laugh grimly at the fact that Roz actually is dealing with Tory against Socialist, not Whig against Whig, ha ha! But why, asks Lance Mannion, why did Ring Lardner have to spend a year in jail for a wisecrack?

First, they win. Then we attack them. Then we laugh at them. Then we ignore them…

Kyogen is truly a fool

Spreading that ego-killing poison

That closes his pupils’ mouths

And lets their tears stream from their dead eyes.

And there I go myself. See? We can’t go forward if we’re always fighting the war of us and them—but we can’t fight at all if there is no them. And we are in a fight, by God. They’re curtailing basic personal liberties, they’re destroying opportunities, they’re wrecking the commonwealth, they’re deliberately making life worse for the rest of us and we’ve got to stop them, goddammit, before they drive us all to a crisis point and betray everything America stands for—

( And Adam Kotsko says, “There has to be some way to react to people wanting the wrong thing other than to just say, ‘Well, I guess we’d better give them what they want.’” And I say, Jesus Christ that’s a dangerous fucking statement. And I say, hell yes. There must. Bring it on.)

I don’t want to yell at the voices in my head. I don’t want to fill a barrel with puppetuses of the right and take potshots. What I want—what we all want, with our earnest tribunals and dialectical traps and sunny hearts—is to knock some scales from eyes. And it’s not that they have to agree with us—if we did not see things differently, we would not be different people, after all. And anyway sometimes it’s our own eyes we’re trying to clear. But on this one point here, or that one, there, if they could just see that they are wrong—

How do we knock the scales from someone else’s eyes?

The upper part [of the kanji for koan] means “to place” or “to be peaceful.” The lower part means wood or tree. The original meaning of this kanji is a desk. A desk is a place where we think, read, and write. This “an” also means a paper or document on the desk.

There is another kanji used in koan. In the case of this kanji, the left side part means “hand.” The literal meaning of this kanji is to press, or to push with a hand or a finger. For example, in Japanese, massage is “an-ma.” So this “an” is to press to give massage for healing. This kanji also means “to make investigation” to put things in order when things are out of order.

“And the student was enlightened.” —But you have to have a student first, see? It’s rare, it’s vanishingly rare for a koan to reach out and strike some random bystander or passerby, someone who isn’t already looking for enlightenment. Sen no Rikyu foils an assassination with a point of etiquette, and while enlightenment doesn’t really pierce a veil in this one, there’s still maybe a lesson we could learn. Gudo, the emperor’s teacher, enlightened a gambler and a drunkard by being decent to him, and speaking plainly, and there’s definitely a lesson there, too, though I wonder about what happened to the drunkard’s wife and mother-in-law and kids. —But still: for the most part it’s students and monks, monks and students, people already engaged in the dialectic, shall we say, who realize there are eyes, and scales to be knocked from them, who are actively seeking the best way to do just that.

—To get back for a moment to those numbers Bob McManus cited, and what they mean, for us, and them: I know why we end up with aggressively regressive tax policies like this, and the politicians who push them; I know what we have to do to stop it from ever happening again. I’ve known for a couple of years, now. All it takes is a piece of paper and a pen. You ready? Write this down:

- A majority of us think that only somewhere between 1 and 5 million Americans live in poverty in the US.

- The actual number of Americans living at or below the poverty level is 33 million.

- 47% of us think the poverty level is $35,000 a year for a family of four.

- The actual poverty level for a family of four is $18,104 a year.

And it doesn’t matter if you do it earnestly, or with a sunny heart in the face of obstinate opposition. It doesn’t matter if you lard your dialectical koans with honeypots for the unwary puppetuses of the left or the right. What matters is that you go out and you find one of that majority, one of that 47%, and you sit down with them, and any way you have to, you show them that they have crucially misapprehended the situation. You show them the facts of the matter. Use whatever frame you can find. Whatever works. And then up and on to the next.

That’s it. That’s all there is to it. And if their ignorance is less blind than willful? If they have different remedies in mind than maybe what I think is best, or you? That doesn’t so much matter. (There are always more scales to fall from eyes. Even yours; especially mine.) We can’t begin to hash out those differences until we’ve reached some basic agreement as to where we all are and what we’re all facing, but once we do—

I have every reason to believe that all our other battles can just as easily be won.

Pupil: Why did the Bodhidharma come from India to China?

Master: I have no idea. Why do people always ask me that?

Unheimlichsenke.

Jed Hartman, who wrote that “Future of Sex” essay back in the summer of ’03, picks up some threads from recent discussions hereabouts and just hauls off and runs with ’em, handing me a real d’oh! moment in the process:

Though I would add that to some extent these days (thirty years after the Sanders novel was published), the presence of homosexuality in science fiction set in the future is more alienating than in contemporary-setting fiction, for a reason much like what I was talking about in my editorial: because there’s so much more homosexuality in the real world (and in contemporary fiction) than in SF set in the future.

Which, yes, of course, and I wish I’d said something to that effect. I started off on a very personal note with a TIME cover from back in a day when it was still possible without trying too terribly hard to grow mostly up in this country and not encounter the idea of same-sex love and desire and didn’t really look back up from it. —Things are different now: studies and anecdotal evidence both demonstrate that among the Youth of Today in America, there’s a marked jump in acknowledgement and acceptance of, and experimentation and experience with—humanity towards—alternate sexualities. At least insofar as gender preference goes. (I don’t know that we’ll be hitting gender-as-fetish anytime soon, but every little bit helps. —Will it hold, this humane attitude? After all, the Boomers were all about peace love and understanding, and look where they’re getting us now; we Gen-Xers, of course, were apathetic and disaffected underachievers, and look what we’ve got to fix. Backlash bites.) (Why, yes. That was a whole slew of unfair generalizations. Goodness.)

Where was I? —Oh. Right. So with this marked jump in humanity, why then does the future in our current fiction appear to be so darned straight? (And vanilla?) —To properly begin to frame an answer would take us all night and far afield; I’d suggest you start with Interlogue Four in “The Rhetoric of Sex/The Discourse of Desire,” when the pissed-off ventriloquized puppet takes over and rants for a bit—but I don’t want to tackle the big amorphous things Down There, crawling about the foundations to the tuneless tootling of shrill pipes; I want, for a bit, to pretend that history progresses; that there is a Big Picture; that with Metaphors I can construct Conceits and with Conceits I can grasp Concepts and shove them about to make pleasing Patterns that line up neat as you please, oh, I get it. So: first, I’d note that the fiction we’re finding wanting in this particular is outlined and written and produced by the Boomers and Xers and not so much the aforementioned Youth of Today. And second, I’d note that, much as none of us is as dumb as all of us, none of us is as normal; and third, I’d note that maybe the uncanny valley applies to more than just robots and rotoscoped CGI.

Ah, but here we’re playing with conceptual dynamite. Any time you start labelling this normal and that ab-, this human and that in-, you set somebody whether you like it or not up to play the ventriloquized puppet—sorry; chances are you haven’t read the essay. The Other, then: the One Who Isn’t. (Normal. Human. “Would you actually argue that I am, whether with my breasts thrust into black leather or basket heavy in a studded jock, the One Always There, who, when everyone else is redeemed, can be thrown to the dogs, at the eye of the patriarchal cyclone you’ve already located as the straight white [need I add?] vanilla male?” —To quote the aforementioned puppet. Did I mention it was pissed off?) —So let me repeat myself: none of us is as normal as all of us. And when we pitch our ideas for consumption beyond our immediate circle, we tune them to our idea of all of us, or as many as we can stomach: that matrix we all keep in our heads of what will fly and what won’t, what’s acceptable and what’s not, what’s titillating and what’s beyond the pale, what plays in Peoria and what doesn’t, what’ll run up the flagpole and who’ll salute it. What’s heimlich, and what’s un-.

(Yes, I know: there’s more than one: there’s a myriad alls for all the myriad audiences we could dream up; there’s Peoria and there’s Hollywood and there’s the Great White Way; there’s the MIT SF Club, and the one at Hampshire College; there’s even ways to pitch the same piece to more than one all at once, and never they’d know the difference. I know. Let’s brutally simplify it and peg one hypothetical all to the right of that graph up there, the axis labelled “fully [careful! dynamite!] human.” —The mechanism such as it is would be the same for whichever all you’d care to pick.)

As, then, an idea, a behavior, a way of being Other, approaches in familiarity that matrix of behaviors and attitudes we’re assuming comprises this asymptotic all, it climbs the red line marking the favorability of the all’s assumed emotional response: it’s a curiosity, it’s something new, something exciting, ostranenie; whatever New Wave is current can leap out and play with it and build strange weird glorious frightening (dull, turgid, inexplicable) shapes with it. —But as it gets even closer, goes from something conceivable to something that could conceivably affect us (transform us, replace us), it hits the cold dark heart of the Unheimlichsenke. (“Oh God I am the American dream…”) We push it away. With the most benign of reasons, sure: why should we bother; they have their own stories; it’s not our your their place; and anyway, if we foreground protagonize celebrate it, it will all prove too distracting, and we can’t sell it to boys aged 16 – 24. Best just to let it happen when it happens of its own accord. —Which is never, if we don’t push it.

Did you notice how the assumed matrix that made up that mythical, asymptotic all became we, and us? —Yeah. You’ve got to be careful about that.

Of course, this fable has a happy ending. History progresses, you see. Things get better. Having enthroned that all, having become aware that we’ve so enthroned it, it becomes our duty to broaden flatten spread it all as far and wide as we can. To open it up to as much as possible. (The ultimate futility of this task is no excuse.) —And our graph foretells a happy ending, doesn’t it? Things do get better.

Don’t they?

(Look at all the Assmissile jokes and ask yourself: what is so goddamn funny—what is so insulting, really—about enjoying anal sex? What is so belittling about being penetrated? —Don’t laugh. The ventriloquized puppet is still furious, and there’s a lot more to it than maybe you first thought.)

Um. Okay. That got a little stranger than maybe I’d first thought when I set out. Certainly longer. —What else was I up to? Right. More from Jed:

(Aside: It occurred to me recently, while reading a Human Future In Space story in Asimov’s in which there are actual homosexuals, that I neglected something in my editorial: it’s traditionally okay to have queer and/or kinky people in HFIS stories as long as they’re decadent and jaded and world-weary. This realization led me to decide that I want to write an Absolute Magnitude-style Starship Pilot Adventure Story in which the dashing starship pilot jock hero is gay but not at all decadent.)

Well, yes, but: there’s more than one dichotomy here. It’s not just straight/gay (straight/queer; vanilla/every other flavor in the universe); it’s active/passive, dominant/submissive, masculine/effeminate (not, note, feminine), penetrative/penetrated. There’s a lot of borders to shall we say interrogate here, and some are easier than others. A female character taking on masculine attributes—those ass-kicking chicks, in other words—they’ve made it past the Unheimlichsenke and are rapidly climbing the final asymptotic all. (For some values of all, yes yes.) A tomboy dyke with sufficiently feminine touches and an unrequited crush on the ingénue? What harm could she possibly do? (And we could bring up the male gaze, but let’s not; it’s late.) —A male character taking on effeminate attributes, though? As some would have it gay men must do: penetrated, submissive, passive, decadent, jaded, world-weary, distant, push away, push away, into the cold dark heart of the Unheimlichsenke, and that’s why Assmissile jokes are so funny. To some.

Our great hope here? Aside from the old reliable engine of slash, and all it’s been able to do? (Have you watched an episode of Smallville? It ain’t great, but damn.) —It’s yaoi. Go, baby, go!

What else? —I’ve got one more move to make in the “long explore,” as Lance put it; it was maybe going to have been two, or one-and-a-half, but I think I took care of that with this unlooked-for aside. I want to peer more at Jed’s original essay, and the why and wherefore of it, and some of the things that are going on outside the circle he’s drawn and examined, that maybe can be sources of pop-culture juice for engineering the epiphanies he’s looking for (but also, making it harder for those epiphanies to be engineered: “They have their own stories,” after all). And I want to look at what happens when you misuse that space, that grace I outlined; what happens when you try to engineer an epiphany and fail. (It’s not that they can only be epiphenomena, these epiphanies. I don’t think. I hope not. But it has to look like they are. I think. Maybe.) —And I’m gonna do it in 1500 – 2000 words. Oh, yeah.

Before we leave the grace of this in-between, backstage space we’re in here and now, though, let me point you in another direction, away from the straight/queer border and towards one that’s more between male and female, and how SF allows (again) a pushmepullyou of ostranenie and the unheimlich. —It involves Dicebox, which is the Spouse’s comic, which is maybe why I’ve been reluctant to bring it up, and maybe I’m a dolt; anyway, here’s cartoonist Erika Moen playing with some of the same ideas:

While a sci-fi story, it is impossible to lump it into any of the common stereotypical categories. It is not an adventure, it is not a hero’s story, and while futuristic gadgetry is present, it is hardly relevent. With most sci-fi stories the location and time are just as integral characters as the protagonists; the audience is there to be swept up in the exotic future. Manley Lee places the chronicle of Dicebox in a science-fiction environment not because that setting is pertinent to the development of the story but because it gives her the freedom to break her characters out of modern day gender stereotypes and rules without having to justify her decision to her audience.

So: one more move, and then I’ll see where I’ve ended up.

The fulness of time.

And anyway, you get right down to it, it was all little more than a side effect.

Sanders wasn’t trying to change my life or anyone else’s with The Tomorrow File. He just wanted to take the usual fare of his Palm Beach thrillers, the tropes of power and money and sex and intrigue, and spin them up as unusual fare, fresh and strange and even a little bit alien. And SF is a mighty fine tool for the job, though it can be a bit on the brutally efficient side as it so aggressively, even didactically, asserts the setting isn’t Kansas anymore. Ostranenie! Unheimlich! —Nicholas’s relationship with Paul is at once a detail of the overall unheimlich setting—bisexuality is no big deal in this brave new world—and itself a technique to foster ostranenie—potboiling sexual intrigue rendered suddenly strange and alien: “I had been in bed with Paul.” (And as such, it works quite well. Certainly stuck in my mind. —I think it was about Wild Things that some critic somewhere said something to the effect that bisexuality really shakes up the noir genre, kicking wide open the question of who can betray which for what, exactly—and yes, it does, indeed, but remember that everything new was old in its day. Even ostranenie; especially the unheimlich.)

But the thing about any tool no matter how mighty fine is that once you’ve used a hammer for a while you start to expect the nails. Read enough SF and you come to expect those unheimlich touches, the ostranenie of another world. It is itself familiar, usual, canny, heimlich. It’s what you opened the book for in the first place; that door damn well better be dilating by page three or you’re taking your custom elsewhere. —This is neither a good thing, nor a bad thing, it’s just a thing, and savvy writers and readers take it into account, ringing ostranenie games off their own expectations of the unheimlich as naturally as breathing. —But because Nicholas’s sexual relationship with Paul was aggressively, even didactically presented as one of the details that set the world of the book apart from the world around it; because it was an SF book; because as a reader of SF books, I’d come to expect, accept, even crave those details that deliberately set their worlds apart from the world around me—therefore, the book’s high unheimlich concept I accepted without hesitation. And that’s the twist of paradox, right there, that allows Nicholas to insist that even though he obviously wasn’t what he was, he still could be what he is, if only you’d let him. In meeting the writer halfway in order to set ourselves aside for a time in that other world, we also find ourselves unknowingly giving Nicholas the grace he needs.

So I’d had an epiphany, yes—but it was an epiphenomenon.

This uncanny æsthetic two-step, this strange state of grace—don’t mistake it for a necessary and sufficient condition. All art plays with ostranenie; pushing you over the brink is how we get to sensawunda. (Pulling you back: Oh, I see! Oh, I get it!) —Much as SF’s ability to make you take literally sentences that usually make only figurative sense gives the writer a more expansive word-palette than otherwise, the expectation that SF will of course be rich and strange allows it more room for accidental grace and pushmepullyou gamesmanship. (But that’s theory. Praxis: how does SF as a genre limit the sorts of sentences readers will take seriously? How do expectations of wonder and estrangement limit the otherworlds we can build within it?)

Necessary and sufficient or not, though, that space is central to the question of whether or not “Time’s Swell” is an SF story.

Now, it’s not a very good story. It’s a mood piece written in a muddle of first-person past- and present-tense that’s a universal solvent: salient details dissolve into a declamatory mush. As “artsy, shallow lesbian erotica,” about the best one can say is it doesn’t use “slick” as a transitive verb. But right out of the gate it aggressively, even didactically insists:

I remember nothing from before this place.

I ask her. Sometimes she is silent. Sometimes she tells me that she does not know, that she met me here, six months ago, that she knows nothing about my past. And then there are the days when she tells me that we’ve traveled through time, that we have come from the future and are trapped here. She tells me that she was a temporal scientist, that I was her project. That I am modified and enhanced for survival, for time travel, for perfection. Those are the bad days.

Sometimes I try to argue with her. If I am so altered, why do I look human? She has an answer for everything. Something about 23rd-century technology and spaceships that can move across time. It’s crazy.

Because we’re reading an SF story (no, I’m not tautologizing; bear with me), we expect a certain degree of strange and uncanny detail. Because we expect it, we accept it when it presents itself. And because we accept it, we don’t question the other details that support it: the extreme, impersonal detachment of the narrator from the people and the world around her, her simple declaration of things we’d otherwise take for granted, the eerie sense of timelessness that wafts languidly throughout (“The ahistorical dreamlike landscape where action is situated, the peculiarly congealed time in which acts are performed—”? Perhaps. These do, after all, occur almost as often in SF as they do in porn). The story depends utterly on these other details to get done what it sets out to do, and these other details depend utterly on the idea that (for whatever reason, it doesn’t matter) the narrator has come from the future and is trapped wherever here is. —It’s the height of folly these days to proclaim that something is the height of folly (we raise that bar on an almost daily basis, and yet still keep clearing it with ease), but to insist, as does Don, that the “authors could have easily removed all SF content and the story would not have been changed in any significant way” is to have let the point pretty much pass you by. It’s the obverse of McCarty’s Error: James McCarty, writing for the Cleveland Plain Dealer, confronted by a book that hinges on the peculiar properties time exhibits as one’s velocity approaches the speed of light, had this to say:

To label The Sparrow science fiction is an injustice and downright wrong.

McCarty’s excuse was that he thought The Sparrow was, you know, good. Don’s is that “Time’s Swell” wasn’t what he expected. But it’s the same basic canonization mistake—just different sides of the fence.

Some people have suggested that since Jed Hartman’s “Future of Sex” editorial called for more SF that imagines something other than an entirely heterosexual universe, then Strange Horizons must be practicing “literary affirmative action” by publishing such (shallow) stories as “Time’s Swell.” Okay, sure. The same way all the prominent SF magazines are practicing literary sexism by publishing so many shallow stories that star heterosexual characters.

Well, no, not quite the same way: the prominent SF magazines don’t proclaim to all and sundry that they intend to practice literary sexism by publishing so many shallow stories that star heterosexual characters. —To be fair, neither did Hartman proclaim, per se: he just said he’d noticed a lack, laid it out pretty clearly, asked for pointers to stories that addressed it. “Whenever I read such a work,” he says, of the typical sort of SF he’s been reading and found wanting, “it makes me wonder why the fictional society of the far future is less sexually diverse than early–21st-century America,” and it’s hard to argue with him. (Me, I might wonder why the SF of today isn’t nearly so adventurous on the fronts of identity and sexuality as the SF of the New Wave, but that’s a specious comparison; don’t mind me.)

Yes, it’s disingenuous to pretend that when an editor of a fiction magazine asks for pointers to a certain type of story, they aren’t proclaiming, or at least setting forth a de facto agenda. So what? Editors don’t just correct spelling and give the grammar a once-over. Selecting stories based on theme and style and intent and voice to further their ideas of what makes for good pieces and a good magazine? That isn’t “affirmative action,” it’s what editing is. —Like what Jed Hartman’s doing with his editorship? You’ll buy more, or read more, whichever’s appropriate. Think his agenda’s leading him by the nose to pick stories you don’t like over stories you do? Take your custom elsewhere. His fortunes will rise, or fall, accordingly. (I understand there’s a whole science devoted to this phenomenon, or something. —The canon that results, by the way? Epiphenomenon.)

So the immediate question isn’t “Is publishing ‘Time’s Swell’ an act of ‘literary affirmative action’,” but “Is ‘The Future of Sex’ leading Strange Horizons to publish the sort of story that’s driving the punters away in droves?”

I don’t know. You got me. I haven’t dug into publishing histories or traffic reports, and I’ll leave all that to someone who cares more than I do. But to this layperson’s eye, Strange Horizons doesn’t appear to be hurting, and if I didn’t like “Time’s Swell” all that much myself, others who know as much or more than I do liked it fine. So there you go.

But at least it’s a more immediately interesting question than “Does publishing ‘Time’s Swell’ challenge my personal notions of what SF can’t do and mustn’t be?”

Could be belongs to us.

The second time I encountered the idea? I dug my way to the bottom of a paper bag full of paperbacks from the Breckenridge County Library’s annual fundraising book sale and came up with this—

I had been in bed with Paul Thomas Bumford, my Executive Assistant. He was an AINM-A, an artificially inseminated male with a Grade A genetic rating. We had been users for five years, almost from the day he joined my Division.

Paul was shortish, fair, plump, roseate. He wore heavy makeup. All ems used makeup, of course, but he favored cerise eyeshadow. Megatooty, for my taste.

Strangers might think him a microweight, effete, interested only in the next televised execution. In fact, he was one of the Section’s most creative neurobiologists. I was lucky to have him in DIVRAD.

The narrator is one Nicholas Bennington Flair; he’s young, brilliant, anethical, powerful, rich, gorgeous; that’s the opening to chapter X-2, which starts on the third page of “Mr. Bestseller” Lawrence Sanders’ 1975 novel, The Tomorrow File. It’s not, let’s get this out of the way, a very good book—it’s your basic beach-blanket brave new clockwork 1984, a dystopic vision of a far-flung future (1998!) full of kinky sex, freighted slang, and petroleum-derived foodstuffs. “Every year our bread became fouler and more nutritious,” says Nicholas, and that pretty much sums up the book’s moral tone. —I read it not too long after I saw that TIME magazine cover, somewhere between 11 and 12: old enough that I’d read any number of trashy potboilers in which men and women occasionally did the oddest and most obliquely described things to each other in and amongst the action and skullduggery; young enough that I was still trying to figure out exactly what. The mechanics were problemmatic: which was doing whom where, exactly? And in God’s name, why?

(Oh, shush. I was shy and bookish and a late bloomer.)

So meeting Nicholas Bennington Flair pretty much for the first time like that, having him so casually announce

I had been in bed with Paul

when just moments before he’d been flirting outrageously with his boss, Angela Teresa Berri, Deputy Director of the Satisfaction Section of the Department of Bliss (formerly the Department of Public Happiness, formerly the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare)—“Her nipples were painted black, a tooty fashion I found profitless”— It was another door, another seed, another bite, another slippery inch down those slopes. To have gone from zero past that image straight to a protagonist so openly, unapologetically queer! And more to the point: the protagonist of a Zukunftsroman. —Had Nicholas been narrating a contemporary beach-blanket thriller, he’d’ve been an alienating figure. No matter how exotic the locale, he’d’ve been insisting he was with all his queerness here and now, and I could look around me and see that this was not so. But science fiction—specifically, future-fiction, no matter how ham-handedly wielded, no matter that his once-future is now our past—SF gives him a certain license. He’s insisting that he and all his world could be, and inviting you to step awhile in his shoes and see the sights.

(We’ll leave once was for another time, and let’s not even try to tackle phantasy’s always already. —While the pieces of this essay-thing lay fallow, Jo Walton went and said the following, as neat as you please:

At twelve, The Dispossessed turned my head inside out on politics, making me question everything I’d seen as axiomatic. At fourteen Triton did the same on sexuality. What SF did was made me consciously aware of how the world was, of the things the world accepted as normal, and made me constantly question those things instead of taking them for granted. All SF did this for me. Heinlein did. Asimov did. Niven did. SF gave me the worldview of “this is a way of arranging things” rather than “this is the way things are.”

(So there you go.)

Which is not to say that The Tomorrow File is a very queer novel, mind. Sanders was “Mr. Bestseller,” after all; he’s not out to freak the punters, much less raise their consciousness—just titillate ’em on their beach blankets with a mere soupçon of épater. Nicholas talks a mean game—

“I’m bisexual,” I admitted. “By intellectual choice and physical predilection. I think most objects are, admittedly or not. The sexual preferences of obsos were conditioned by biological necessity and hence by society. Neither prevail today. Efs can procreate without sperm. The preservation of species is no more vital than its limitations. Now we can indulge our operative natures, which are androgynous.”

“What does all that mean?” she asked.

“That I like to use both efs and ems.”

“Oh, yes,” she breathed. “Use me.”

Ah, amour! —But! The only em Nicholas ever actually “uses” in the course of the book is young, effeminate, pudgy Paul, his assistant, his foil, his nemesis; him alone, as opposed to a score of efs, from the tootily black-nippled Angela to a couple of distressingly declassé Detroit girls. And while the book entire is something of an exercise in clinical detachment, it’s still telling that there’s not the slightest spark of lust or desire or longing in how Nicholas deals with Paul: he sees him; he just doesn’t want him. Only their final encounter is described with anything approaching the particularity of Nicholas’s encounters with those varied and sundry women, and that enough to make it clear it’s Nicholas who tops, while Paul Bumford bottoms. Our narrator’s essential masculinity, you see, has thereby not been compromised: buggering a subordinate is still splashing about in the shallow end of the genderfuck pool, a step or two beyond a couple of it-girls lugging it up on the dancefloor for the benefit of Mister Kite. —Also, and as another for instance, there’s the problem of the book’s only authentic queens:

Through the trees, drifting, came the two young ems, neighbors who had so amused my mother. Wispy creatures from the adjoining estate. Both barefoot, wearing identical plasticot caftans decorated in an overall pattern of atomic explosions.

They were carrying armloads of natural flowers: something long-stemmed and purple. They asked if they might leave them on my mother’s grave. I nodded. They put them down gently.

“She was a beautiful human being,” one of them said. The one with a ring in his nose.

“Yes,” I said. “Thank you.”

“Who were they?” Paul breathed when they ran away. Startled fauns.

“Friends and neighbors,” I said.

“The kind of ems who give homosexuals a bad name,” Paul said. “Flits.”

“You’ve changed,” I told him. “You wouldn’t have said that a year ago. In that tone.”

“‘When I was a child,’” he quoted, “‘I spake as a child. When I became a man, I put away childish things.’”

“Now I’ll give you one,” I said. “‘Upon what meat doth this our Cæsar feed, that he has grown so great?’”

It can’t help sniggering, this book; pointedly opting not to judge the morality of the characters, the actions, the era it pretends to find so morally empty. Sanders, after all, is very good at letting his audience feel superior to the people who are indulging in the very vices they themselves would indulge in, if they had a chance. (How else does one become Mr. Bestseller?) —What’s significant is that for once bisexuality—a man’s bisexuality—is presented as one of those vices. What’s significant is that Nicholas’s relationship with Paul is vital to the book: while Nicholas himself might tell you it was wanting life to have more charm that was his downfall, or perhaps a morbid conviction that the only worthy moral verities are those drawn from an obsessive contemplation of the works of Egon Schiele, we know it’s the way he treats Paul throughout that’s key to where he ends up, and why. —And keep in mind: I was 12, maybe 13, and trying to fit together a couple of very big pieces of how the world works that had rather haphazardly been given to me: it is possible for men to like other men; here, then, is a man who likes other men; here is that man in a relationship with a man he likes. Heady stuff.

So—mediocrities and problematizations real and manufactured aside—I’ve got to give credit where credit is due. Because Nicholas Bennington Flair did not insist he was what he was, but instead that he could be what he is, if only the reader would let him, he became in an odd sort of way the change some wanted to see in the world. My world, if nothing else, became bigger because of him, and this book, and for that I have to tip my hat. Right time, right place, maybe; maybe my world would have achieved its intended size some other way, if I hadn’t found this book at the bottom of that paper bag. To quote Delany, stupidity is “a process, not a state”—

A human being takes in far more information than he or she can put out. “Stupidity” is a process or strategy by which a human, in response to social denigration of the information he or she puts out, commits him- or herself to taking in no more information than she or he can put out. (Not to be confused with ignorance, or lack of data.) Since such a situation is impossible to achieve because of the nature of mind/perception itself in its relation to the functioning body, a continuing downward spiral of functionality and/or informative dissemination results. The process, however, can be reversed at any time…

Maybe. But for all its flaws, The Tomorrow File was the key that opened the door; it’s what got the job done. Kudos.

Did it? —Get the job done, I mean. It takes a special sort of hubris to label homophobia qua homophobia as stupidity, shamefully toeing the dirt across from the blissful state of ignorance I’d been in, before I read Mr. Bestseller’s dystopia. —Whatever epiphany I might have realized in those tweenage days, it wasn’t until Stars in my Pocket like Grains of Sand that I understood—that I knew, in my bones—that a man liking another man was no different than me liking, say, Eva. And that was in my senior year of high school. Sophomore year, and altogether elsewhere, there was that unfortunate incident after a biology class, involving Bobby Brown, and that song Craig had put on a mix tape. “Hey there, people, I’m Bobby Brown,” I sang—sneered, really—“some say I’m the cutest boy in town,” and then I was on the floor having crashed into a lab table on the way down. Bobby stood over me, glaring, which was shocking—he was such a quiet, geeky guy, so much so that a quiet, geeky guy like myself felt perfectly—safe? justified?—in, well, mocking him. A startled faun. Where the hell had that tackle come from? He stormed out of the classroom as I pulled myself to my feet. —And if you’d asked me at the time I’d’ve said I don’t know, I had no idea, and if you’d asked me at the time I’d’ve said that wasn’t what I’d meant at all. It was just the congruence of the name. Mean-funny. You know?

But now I’m not so sure; I remember that little surge of spiteful triumph, that snigger just before he knocked it out of me, a rush that was as out of all proportion to the stupid, stupid joke as his sudden burst of anger. Why had I felt so safe? So justified? Why had he felt so threatened? “Oh God I am the American dream…”

What goes through your mind.

1. First, establish your bona fides.

I’ve shot guns. I’ve enjoyed shooting guns. Had a pump-action BB gun when I was a kid: twelve progressively stiffer pumps with the plastic stock that levered in and out under the cold metal barrel and you were ready to go. Coke cans stacked in rough pyramids in the chicken barn would tremble at my approach, let me tell you. —It wasn’t till I got to 4-H camp and had a chance to shoot some bolt-action .22s that I figured out I was shooting weird: I’m right-handed, but left-eyed, so I set the butt against my left shoulder, peered through the sight with my left eye, wrapped my left finger around the trigger—and had to awkwardly reach over and across with my right hand to work the bolt to eject the old cartridge and load a fresh bullet. (They didn’t have a left-handed bolt-action .22, and anyway, I wasn’t really left-handed.)

2. But.

HOME DEFENSE

(Three gun match)

Scenario—About 10:30PM you are dressing in your bedroom just after stepping from the shower. Suddenly you hear your daughter scream from the direction of the living room. You grab your home defense weapon and head in that direction. As you come on the scene you see your daughter on the floor, a stranger on top of her, knife to her throat and tearing at her clothes. Proceed as necessary.

Procedure—Start with back to wall three feet from corner with weapon in hand. At signal jump to corner, engage your daughter’s attacker, then accomplice who’s [sic] in foyer. Hit plate to stop clock. Run twice each with pistol, shotgun, rifle. Eighteen rounds minimum. Roll dice to determine which order you will use the three weapons.

Paladin Score—Combine all six times for score. Five second penalty for hits on daughter. Five second penalty for not attempting to use cover.

We have some gun magazines in the house; useful for photo-reference and technobabble. The little ditty above is a sidebar exercise from the “Tactics” column in the March 2000 number of Combat Handguns. One Rick Miller. Here’s a full column that he wrote. “When I am not at home, my wife has standing instructions to stay in the bedroom in the event of an intruder.” —Can I just say that me an’ the Spouse have not devised a game plan to cover an intruder in the house? Have not even given it a moment’s thought? Beyond the usual what was that noise oh it was the cat?

There’s a third-page vertical ad next to the “Home Defense (Three gun match)” sidebar exercise. It’s for the Quik2see magazine-mounted flashlight system, and it’s got a picture of a grimly determined man holding a Quik2see-equipped handgun in a nice-enough cup-and-saucer, while a woman cligs to him, fearful, behind and a little to one side. From the lighting and the placement of the night-table lamp, it’s evident they’ve just sat bolt upright in bed. What was that noise?

Ideally, everyone should congregate in the master bedroom or other safe place, where the defense weapon is stored. If that is not possible, the children should be instructed ahead of time to lock themselves in their bedrooms in case of emergency, while you sort the situation out, and your spouse calls the police.

(Oh, to be sure: you could find similarly unselfconscious descents into ghastly self-parody inside of five minutes with any particular magazine from the other side, wherever you might locate that other side to be; that’s not the point. What else are bad writers and advertisements for? —I’m still trying to get past the five second penalty you take if you hit your hypothetical daughter with a hypothetical hunk of metal a notch under a centimeter across traveling at about 350 hypothetical meters per second.)

3. Bona fide.

Our second German shepherd was named Duchess. (Full American Kennel Club name: Duchess Eilonwy. Our first was Indigo. Our third? Schtanzi, after Mozart’s wife.) She had a bad habit of catching bees in her mouth, and once she teamed up with a neighbor’s dog and ran down all but one of our geese, which was a bad, bad thing, but me and my sister and brother hated the geese, so we didn’t mind so much. We always had the plan of paying a stud for a litter of German shepherds at some point, so she was never fixed, and when she was in heat stray boys and otherwise respectable male workin’ dogs would slip the leash and be seen loping through the garden, sniffing up the front porch. “Scare ’em off,” Dad would say. He’d hand me the BB gun. “I’m serious.”

I came home from school one day to find Duchess standing hindquarters-to-hindquarters with a liver-colored stray. She was whining and pulling against him and he, the poor dumb sonofabitch, was pulling against her, and neither of them was going anywhere but in circles in the driveway. I yelled, I waved my hands, I threw gravel. I kicked him. I kicked a goddamn dog. I had no idea what copulatory lock was. All I knew was he was hurting Duchess and I wanted him to stop.

Five minutes later, maybe ten, he fell out of her with an anticlimactic plop and headed for the woods, his tail between his legs, his head down. We let Duchess into the house and made much fuss over her. There were no puppies. —Six months or so passed, and here came the liver-colored stray again, sniffing at the front porch, skulking about the garden. I went out and yelled at him. Waved my hands. “Go on! Get out! Get the hell out! Don’t come back!” Threw a rock. He scooted away, slowed down, circling, started edging back. Guilty look on his face: dude, I know, it’s wrong, but come on, cut a fella some slack?

I went and got the BB gun.

The first shot caught him by surprise. He yelped and spooked. I’d aimed at his backside and stung him, and as he started to trot down the driveway I went walking after him, pumping up the gun, and stung him again. And again. And again.

Our driveway was a little over a mile long.

Just past the second cattle grate he lay down in the ditch and I stood over him, crying, and shot him over and over again, watching the little welts appear on his belly, his haunches. His flopped-over ear was swollen. I’d hit it without realizing on the way down. “Get out!” I was yelling. “Get the hell out of here! Leave us alone!” Could I hit his tail? Yes, yes I could. He wasn’t even looking at me, wasn’t looking at anything at all. Just lay there in the ditch, in the dust, shivering.

I stopped before I ran out of BBs.

“Get out!” I said, and I turned and ran back to the house.

We never saw him again. There wasn’t any blood in the ditch when we went to school the next morning; then, there hadn’t been much blood at all in the first place. I didn’t shoot the BB gun much after that. We lived right on the Ohio River, across from an Indiana state park, and every autumn weekend you could hear the rifles popping like occasional firecrackers.

4. Balletic.

“What a wonder is a gun,” sings Charlie Guiteau. “What a versatile invention! First of all, if you’ve a gun—”

Click-chack.

“—everybody pays attention!”

5. And then.

“Why do I recommend two pistols in the night stand?” says our friend Rick Miller.

It is simple. If you must search the house, the second weapon is for your spouse to use. If you confront the intruder and you lose, the rest of the family won’t be defenseless. It is a good idea to make the second gun of similar type and caliber to the first, to avoid confusion in time of stress.

I haven’t shot a gun since I was, what, fourteen? I’ve held a pistol since then, and it’s true, what they tell you: it’s colder and a lot heavier than you expect. I have no intention of ever buying a gun, or of ever having one in the house. One of these days, though, I probably will make it out to a shooting range. Just to see.

Every gun nut I’ve ever known, which, granted, isn’t many, has every one of them been a nut about safety and maintenance. Not a one of them ever had a home invasion drill, that I know of. Or standing orders for their spouses in the event of a bump in the night. None of them had guns in order to feel safer.

A week ago, maybe fifteen minutes after I got off the bus, Michael Egan got up from where he’d been sitting on the sidewalk and went up to Vincent Stemle as he was getting off a bus. They got into an argument about something. Prescription pills, somebody said. Spaynging, somebody else said, but that was on Fox, and who believes them? —Egan started slapping Stemle. Knocked his hat off. His glasses. Stemle pulled a .357 and shot Egan three times, then turned and ran.

Did he say go away? Get out of here? Leave me alone?

“He almost thought everybody had something out for him,” [Willie] Spakes said.

This ahistorical dreamlike landscape where action is situated—

—broke asunder and fell from her hand. A blinding sheet of white flame sprang up. The bridge cracked. Right at the Balrog’s feet it broke, and the stone upon which it stood crashed into the gulf, while the rest remained, poised, quivering like a tongue of rock thrust out into emptiness.

With a terrible cry the Balrog fell forward, and its shadow plunged down and vanished. But even as it fell it swung its whip, and the thongs lashed and curled about the wizard’s knees, dragging her to the brink. She staggered, and fell, grasped vainly at the stone, and slid into the abyss. “Fly, you fools!” she cried, and was gone.

Once more, Patrick Nielsen Hayden saves the day.

Well, he did. —I finished Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell a bit back, and enjoyed it quite a bit, finding the digressive length (both of opening acts and footnotes) muttered over elsewhere to be delightful and ultimately necessary: groundwork to build a proper floor from which to kick off into, well. To say much more would spoil; I’ll just note that magic is abominably tricky to pull off, and Susanna Clarke manages to step nimbly from Potteresque cantrippery to Lovecraftianesque occultiana (the latter as architected, perhaps, by Peake) while playing allegorical games on several levels: John Holbo reads it as philosophy, naturally enough; I read it as writing, with Norrell as critic to Strange’s writer, and if that explains why I still found Norrell the more sympathetic when all was said and done, well, it doesn’t make me any happier about it.

But: the day, and its salvation. While reading it, I’d perk up whenever I stumbled over its discussion elsewhere, like this Crooked Timber post, which led me to John Clute’s review, which I dropped like a hot potato halfway through, when I learned of a plot twist I hadn’t yet tumbled to. (Should have paid attention to those spoiler warnings.) Stung, I slunk back to the book, consoling myself with the idea that I would have seen it coming soon enough, and anyway, the gotcha is the least important part of a plot twist; otherwise, we’d all save time with Cliffs Notes. —What I hadn’t noticed was how the book had been spoiled on a more fundamental level: Clute, you see, tells us that Strange & Norrell is but the first book in a proposed series.

Which surprised me—the book is a long way off from your door-stopping wodge of extruded fantasy product, and though I couldn’t tell you how exactly it doesn’t step like a volume one, nonetheless, it quite clearly doesn’t; it carries itself neatly, of a piece, whole. —Now, this doesn’t prevent it from being volume one of a proposed series, any more than keeling over suddenly in the middle of a jungle prevents Cryptonomicon from being a single book, prequels notwithstanding. And series and sequelæ are pretty much a fact of life in the Beowulf game these days. So I didn’t question Strange & Norrell’s status as volume one of; even began reading it in that light (indeed, couldn’t help but), wondering how the story would go on from here, wondering which characters would play what roles the next time ’round. Wondering, but also worrying, even fretting, because Clarke pulls off her magic trick about the only way you can: by hinting, alluding, suggesting, glossing; by taking crucial bits for granted, by knowing when to let up, so the readers come the rest of the way themselves. And because Clarke’s enterprise is to thin the walls between worlds and bring the magic back, the only place she can go is where Strange & Norrell stops: right up to the gates themselves, or maybe a step or two beyond. The stuff Clute presumes would fill out the next two volumes of Clarke’s three-book contract—the stuff, in fact, he seems to think is missing from the story—would be too much; would leach the magic away by nailing it down. Those gaps, I thought, were there for a reason, and while it’s hardly impossible that volumes two and three wouldn’t be worthless, still: they felt like they’d be mistakes. I began to resent the shadow they cast over what I was reading here and now. —There and then, rather.

So tonight I’m bopping about old posts and threads and decide on a whim to check on John Holbo’s midstream review, where I find this comment from the electrolit Patrick—

Allow me to presume on my small acquaintanceship with Susanna Clarke in order to tell you that John Clute’s assertion that Jonathan Strange was planned as the beginning of a series was entirely pulled out of John Clute’s ass. There is no such plan. Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell is a complete work.

Susanna has more recently said she might write a different novel with the same background, but it would not be about the same people. And yet people keep repeating Clute’s entirely erroneous assertion that the book is the start of a planned-out series à la Jordan, Martin, Donaldson, etc. It’s not, and it never was.

And it’s astonishing: not one word of the book I read has changed, and yet it’s suddenly so much better. What a wonderful trick! My thanks to you, sir; kudos and hosannahs.

Atlas leans back everywhere.

You’ve seen it by now, I hope? —At the very least, you’ve seen the preview, and I bet you giggled at the bit where Frozone’s looking for his longjohns, which goes a little something like this:

FROZONE:

Honey—where’s my super-suit?

HIS WIFE:

Your what?

FROZONE:

Where’s my super-suit?

HIS WIFE:

Why do you need to know?

A helicopter explodes.

FROZONE:

We’re talking about the greater good!

HIS WIFE:

I am your wife! I am all the greater good you need!

Frozone, of course, gets his super-suit, and saves as much of the day as a sidekick can, with some stylin’ speedskating moves: the great power that necessitates the great responsibility he feels. (Well, that, and the adrenaline rush.) —Hooray for the greater good!

Now, there are some folks tut-tutting this flick for being excessively Randian. “The Incredibles is ‘brilliantly engaging,’ [Stuart] Klawans says—which makes it ‘more worrisome, if you lack blind faith in the writings of Ayn Rand.’” —Which reminds me of a minor strain of Trekkiedom that insists Spock’s bloodless Vulcan logic must in its particulars resemble Rand’s Objectivism, because, y’know, Vulcan logic is logical, and Objectivism is logical, so hey presto. Not entirely sure what those Trekkies do with the image of Spock slumped on the floor, his green Vulcan blood smeared melodramatically along the glass wall, huskily telling Kirk with maddening imperturbability that “it is logical: the needs of the many outweigh—”

Then, it’s not really my problem, is it?

Nor am I entirely sure how to apply a Randian reading to a superhero flick in which the superheroes end up right back in the obscurity from which they came, danger their only reward for pulling on the tights—okay, danger, and some small government help in dodging the occasional catastrophic insurance claim and class-action suit. And their pictures on the covers of magazines. And free bullet-proof supersuits. And the adulation of millions. —But aside from all that.

As with any superhero work, there are echoes and resonances, responses and repudiations of Rand and Nietzsche. That stuff’s built in, like the secret identities and the underwear on the outside: even if you try not to do them, you have to take the time to let the audience know you’re not doing them, which means you end up doing them. Whoops. —So, yes: there’s a there there in The Incredibles, sure, but mostly because it is what it is. Brad Bird wanted to tell a story with superheroes in it; along with that genre comes certain baggage; that he hauls it about without complaint does not mean he’s crafted a candy-colored piece of crypto-Randian propaganda.

For instance: to read the conflict with Syndrome, the villain, as a “class war” of Übermenschen v. Lumpen is to miss the whole point of his costume, his tropical island, his lava curtain, his expendable henchpeople, his Heat Miser hair, his zero-point energy gauntlets. Syndrome doesn’t want super powers. He’s had super powers ever since he was a wee tot: he’s the mad inventor, the kid genius, the gadgeteer: a super-powered archetype with a long and pulpy pedigree. What it is that Syndrome wants is to be a superhero—without, y’know, the pesky bother of all those superheroics. He doesn’t get the altruistic end of the stick; he just wants to shortcut straight to the adulation.

So Syndrome isn’t an unpowered drone with delusions of acting above his station. Syndrome’s an asshole.

Okay, how about when Bob Parr, née Incredible, bursts out with “They’re constantly finding ways to celebrate mediocrity!” Classic Ü v. L, right? —Except he’s griping about Dash’s “graduation ceremony”—for moving from fourth grade to fifth grade. It’s not the people, powered or un-, that are mediocre; it’s the experience. Bob’s railing at the insidious successorized insistence that every moment be special, everything be wonderful, that we’re always happy, no matter what, always game, always up for it, always closing, that we’re always safe and satisfied and sound: the awful logic that actually believes nine hours a day in a fluorescently buzzing cubicle end-running legitimate insurance claims really is a rewarding position that utilizes your talents and skillset in a meaningful fashion that best satisfies your life-goals.

(“If everyone’s special,” sneers Syndrome, whines Dash, “then no one will be.” —Yes, yes. I never said this was a slam-dunk.)

And then there’s the somewhat more grounded criticism of the family’s superpowers, and how they mimic and mirror and reinforce white-bread patriarchal family values, ew, ick: Dad’s hella strong; Mom stretches herself thin to keep up with everyone; the adolescent daughter just wants to disappear; tweener son’s a hyperactive blur—

Bird’s biggest achievement in The Incredibles is to have inflated family stereotypes to parade-balloon size. His failing is that, in so doing, he also confirmed these stereotypes, and worse. Helen mouths one or two semi-feminist wisecracks but readily gives up her career for a house and kids; women are like that.

Klawans again, and again he’s missing a point that superhero aficionados know in their bones—but, more shockingly, one that’s right there on the screen, one of the major themes of the movie, one he checks himself in the very next sentence: “they chafe at their confinement, like Ayn Rand railing against enforced mediocrity.” —Hell, Bill got it, even if he did crib it from Jules Feiffer:

When Superman wakes up in the morning, he is Superman. His alter ego is Clark Kent. His outfit with the big red S is the blanket he was wrapped in as a baby, when the Kents found him. Those are his clothes. What Kent wears, the glasses, the business suit, that’s the costume. That’s the costume Superman wears to blend in with us. Clark Kent is how Superman views us. And what are the characteristics of Clark Kent? He’s weak, unsure of himself… he’s a coward. Clark Kent is Superman’s critique on the whole human race, sort of like Beatrix Kiddo and Mrs. Tommy Plumpton.

Helen Parr doesn’t give up her career for a house and kids because women are like that; she gives it up because a spate of lawsuits drives the supers into hiding, and so she tries to live up to the normal idea of what women are like—and it fails, miserably. Bob’s miserable when he tries to carry the weight of his family on his back alone. Violet blossoms when she’s able to take direct action to save and protect her parents. Dash—well, let’s give Dash props; he knows what he wants all along, and when he finally gets it, it’s a blast of sheer, unadulterated joy that leaves you whooping and hollering and forgetting for the moment the distressing bodycount. The triumph of the movie is seeing the family set aside its constraining, restraining roles and work together to get something done: rather less patriarchal than the good Dr. Dobson might want, I should think.

Of course, at the end of the movie, the status quo is mostly resumed: the Incredibles return to incognito, and though Dash gets to run track, he can’t do it full-out, y’know? Rational, egotistical Objectivism is not followed to its seemingly logical conclusion: they don’t end up living in their supersuits, imposing the super-powered diktatoriat that is their Nietzschean due. —Their secret identities are lies, yes, but not lies to be repudiated: they’re roles, to be put on and taken off as needed—necessary compromises we all must negotiate with the expectations of the world around us. The Parrs’ mistake was to think that the Breadwinner or the Homemaker were somehow more real and true than the supersuits.

No, if you want to read The Incredibles as some sort of Randian parable, then it becomes a tragedy. Syndrome is our protagonist: the genius inventor whose fabulous wealth was created—rationally, egotistically—by the focussed application of his singular talents. He dreams of a world in which cheap, zero-point energy puts the mythic powers of a select few within the reach of us all—the ecstatic epiphany of Flex Mentallo; “Harrison Bergeron” run in reverse, like some madcap technicolor dream. —But here come the Incredibles, representatives of that select few, who destroy his wealth and smash his dream and grind him back into the dust, hogging the glory all to themselves: call it Incredible Planetary, if you like.

“If everyone were special.” —There are some problems it might be fun to have. Y’know?

Looking for Mr. Finch.

Sometimes you wish they’d go for the pith, you know?

Of all the loathsome spectacles we’ve endured since November 2—the vampire-like gloating of CNN commentator Robert Novak, Bush embracing his “mandate”—none are more repulsive than that of Democrats conceding the “moral values” edge to the party that brought us Abu Ghraib.

That really ought to be shouted from battlements, for fuck’s sake, but—and much as I love em-dashes, and the clauses you can tuck inside ’em—there’s no rhythm. No rough music. No beat to pump a fist to.

Still. It’s one fuck of a clarion call.

Fred Clark gets it, too; and if his last line is more stiletto-snark than trumpet blare, well, the stiletto’s the weapon of choice right now in the op-ed alleys of the world.

Some political observers have responded to the electoral map and the exit polls by suggesting that if Democrats want to succeed in the scarlet states they will need to: A) accept the gelded notion of “morality” as a category primarily concerned with the condemnation of sexual minorities; and B) join in and embrace this impious form of piety to win more votes.

This is bad advice. It is also—what’s the word I’m looking for?—immoral.